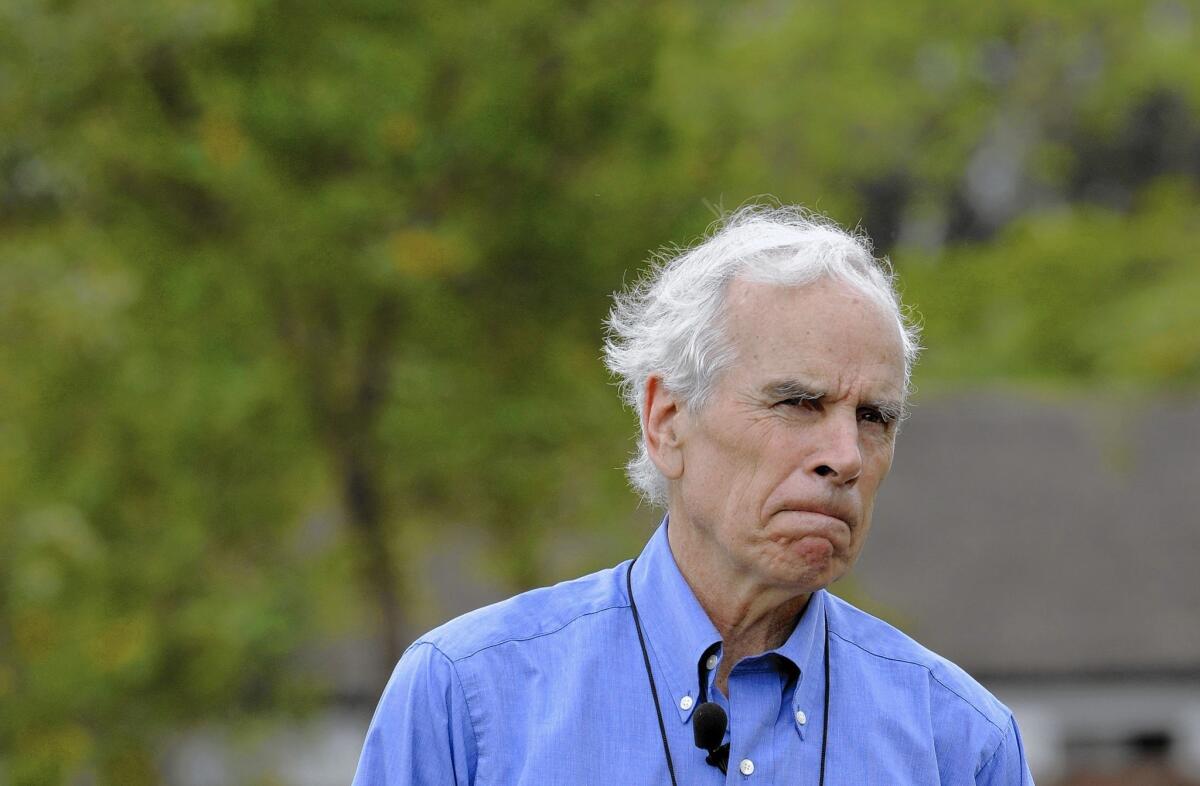

North Face co-founder Douglas Tompkins dies in kayaking accident at 72

North Face co-founder Douglas Tompkins, who abandoned his executive life in the Bay Area to pursue his passion for ecology — and spent his fortune on land purchases in South America as part of a quixotic and sometimes controversial mission to save the continent’s remaining wild terrain — died Tuesday of severe hypothermia after a kayaking accident, Chilean authorities said.

The Aysen health service said Tompkins, 72, who was also co-founder of the Esprit clothing line, was boating with five other foreigners when their kayaks capsized in a lake in the Patagonia region of southern Chile. Tompkins died in the intensive care unit of the hospital in Coyhaique, a town about 1,000 miles south of Santiago.

Chile’s army said strong waves on General Carrera Lake caused the group’s kayaks to capsize. A military patrol boat rescued three of the boaters and a helicopter lifted out the other three, it said.

Tompkins had acquired hundreds of thousands of acres in Patagonia, a sparsely populated region of untamed rivers and other natural beauty that straddles southern Chile and Argentina. On his Chilean land, he created Pumalin Park — 716,606 acres of forest, lakes and fjords stretching from the Andes to the Pacific, an area the size of Yosemite National Park.

Tompkins helped start North Face, an activewear company, in the mid-1960s. At first, it was just a small shop for hiking enthusiasts in San Francisco’s North Beach. It is now owned by VF Corp. of Greensboro, N.C.

Born on March 20, 1943, Tompkins was the son of a New York antiques dealer. He dropped out of prep school and became a Colorado ski bum, and he trimmed trees in Lake Tahoe before starting the shop.

Shortly after, he founded the business that would become the Espirit line with his then-wife, Susie Russell, with whom he had two daughters. The business, and the marriage, eventually had troubles. The couple parted and he remarried. He was reported to have left Espirit in 1990 with a fortune of about $150 million.

He and second wife, Kristine Tompkins — a former Patagonia chief executive and a Californian — went to Chile in the 1990s to devote themselves to conservation efforts, leaving their business careers behind. Tompkins had first visited the country as an aspiring Olympic skier in the 1960s. Now he intended to stay for good.

Tompkins said he wanted to be like the philanthropists of American history who preserved lands that later became national parks. Kristine Tompkins explained the decision by comparing the wilds of Patagonia to what California may have been like 150 years ago.

They lived on the land, preaching ecology and sometimes generating controversy. Tompkins’ efforts to preserve vast stretches of South America was rooted in the “deep ecology” movement enumerated by Arne Naess of Norway, who called for deep transformation of modern society’s assault on nature. They made contributions of land to the Corcovado National Park and Monte Leon National Park.

His activism stirred admiration but also resentment in Chile, where the specter of a rich American buying enormous land resources was viewed warily. He clashed with leaders of Chile’s lucrative farmed salmon business, which he criticized as environmentally destructive, and opposed a dam project in Patagonia.

He appeared to have a tireless passion for the rough mountains and fjords of that land. In 2006, he spoke to The Times of his decision to settle there. He described an early visit: “The clouds were all just hanging around. That was just incredible that day. I thought, ‘This is the place.’”

Twitter: @mcdneville

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.