33 Die, Many Hurt in 6.6 Quake

A deadly magnitude 6.6 earthquake--the strongest in modern Los Angeles history--ripped through the pre-dawn darkness Monday, awakening Southern California with a violent convulsion that flattened freeways, sandwiched buildings, ruptured pipelines and left emergency crews searching desperately for bodies trapped under the rubble.

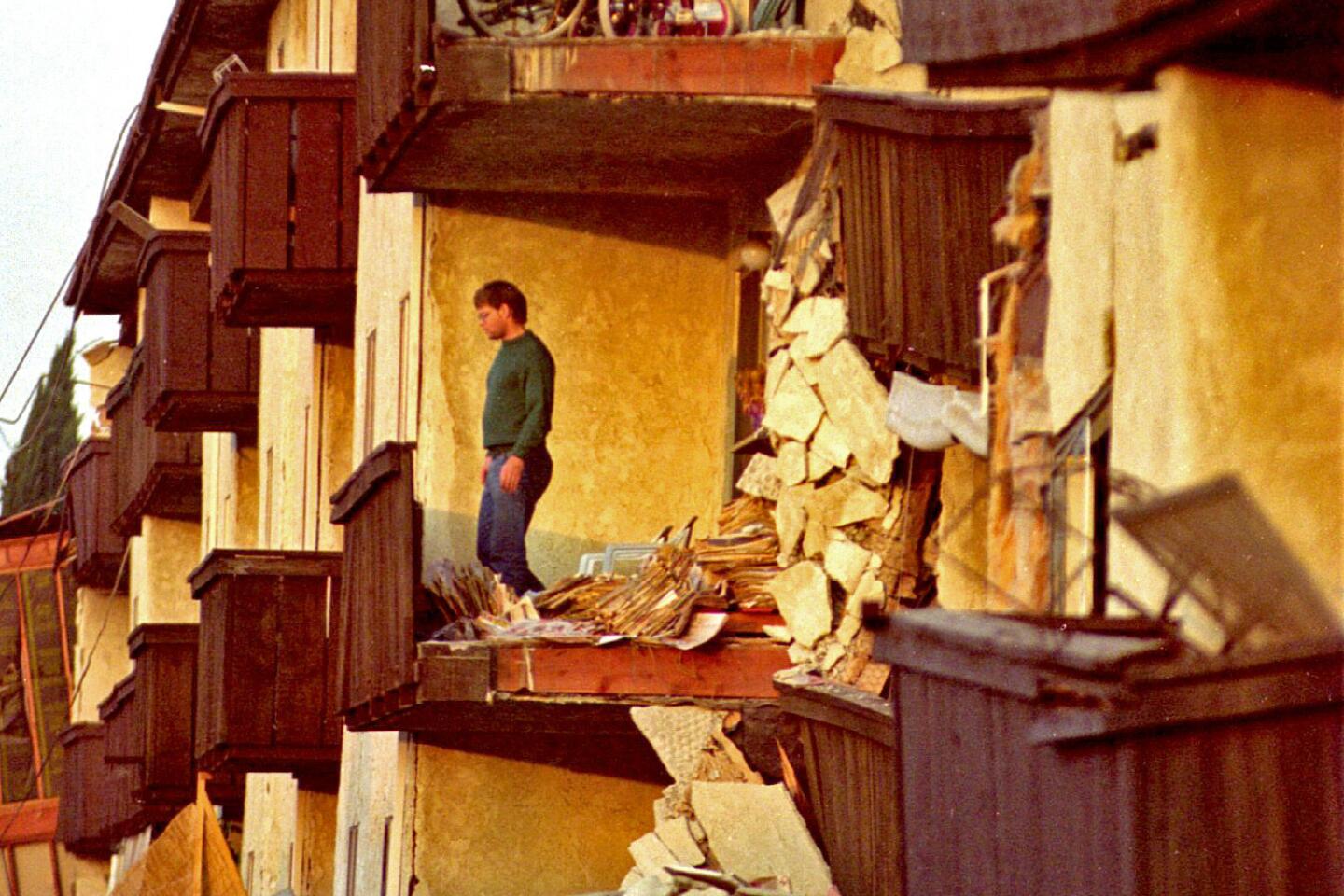

The 10-second temblor, which was not the long-dreaded Big One but erupted so fiercely that it initially seemed every bit as intense, was blamed for at least 33 deaths--nearly half of which occurred when a three-floor apartment complex near the epicenter in Northridge collapsed into two stories.

Triggered by a fault that squeezed the northern San Fernando Valley between two mountain ranges like a vise, the 4:31 a.m. earthquake swamped hospitals with hundreds of injured victims and left thousands more homeless as fires, floods and landslides dotted a landscape that has been visited by destruction with disturbing regularity.

The major developments:

* The death toll continued to grow throughout the day. Fifteen bodies were discovered under the rubble of what had been the Northridge Meadows apartments. Other victims of the quake included a Los Angeles police officer who drove his motorcycle off a sheared-off freeway, a Skid Row resident who may have hurled himself out the sixth-floor window of a Downtown hotel and a Rancho Cucamonga mother who slipped on a toy as she raced to check on her child, striking her head on the crib.

* In a painstaking rescue, firefighters worked more than seven hours to save a critically injured maintenance worker who was trapped under 20 tons of concrete that crumbled at the Northridge Fashion Center’s parking structure.

* Highways across Los Angeles County buckled and crumpled, wiping out major commuter thoroughfares and ensuring that life in this car-dependent region will be disrupted for months. Hardest hit was the Santa Monica Freeway, the nation’s busiest, which caved in at the overcrossing of La Cienega Boulevard, and the Antelope Valley Freeway, which collapsed at its junction with the Golden State Freeway in the Newhall pass.

* Ruptured gas lines and propane tanks sent fiery balls bursting through asphalt roads, engulfing up to 100 mobile homes at three San Fernando Valley trailer parks. Meanwhile, a broken water main on Balboa Boulevard shattered 100 square feet of pavement, turning the street into a geyser.

* The temblor, felt as far as Oregon and the Mexican border, left tens of thousands of residents without power, gas or phone service. In the historic Ventura County community of Fillmore, where brick facades had undergone extensive earthquake renovation in recent years, virtually every downtown business was damaged.

* Late in the day, Mayor Richard Riordan initiated a citywide curfew, making it illegal for people to remain on the streets between dusk and dawn. President Clinton pledged immediate federal assistance while the National Guard was mobilized to prevent looting in blacked-out neighborhoods. Gov. Pete Wison, touring the area in a helicopter, said: “You begin to wonder how much Angelenos are expected to take.”

* Insurance Commissioner John Garamendi, touring areas hit hardest by the earthquake, predicted that local authorities will proclaim many older apartments uninhabitable. He said thousands or tens of thousands of Los Angeles residents may be made homeless.

Had the quake not struck on a holiday, or if it had begun a few hours later, seismologists fear, the damage would have been far more devastating. Even so, Southern California seemed to shudder to a terrifying halt Monday, a day of frantic waiting, dramatic rescues, empty highways and fraying nerves.

“It was a 6.5 on the ‘Richter scale,’ but a 10 on my fear scale,” said Nick Stevens, 40, an Australian tourist staying at the Hollywood Downtowner Motel. “We had been planning to go to Universal Studios, where they have the earthquake ride. Now we won’t have to bother.”

‘It Was Unreal’

Across the smoky expanses near the quake’s epicenter, the scene was nearly apocalyptic. Buildings were left in crumpled heaps. Balls of fire tore through mobile home parks. Geysers gushed out of asphalt streets. For the first time in Los Angeles’ history, officials said, all the city’s lights went out at once.

After touring his northwest Valley district, which suffered some of the most severe damage, Councilman Hal Bernson said: “If you saw Northridge Fashion Center or Balboa Boulevard, you’d think you were in Beirut.”

At least six people fell victim to quake-induced heart attacks. The rest were killed by the temblor and the chaos it induced. A 25-year-old Sherman Oaks man was electrocuted, a 92-year-old Northridge woman died when her trailer burned, a 4-year-old child was crushed by the wreckage of her collapsing home and a veteran LAPD traffic officer plummeted from a freeway overpass when his motorcycle skidded out of control on a buckled swath of the Antelope Valley Freeway.

“His lights were still flashing and he just came tumbling down,” said Andy Jimenez, 33, of Santa Clarita, who watched as Officer Clarence Wayne Dean, 46, plunged off the end of a destroyed bridge to the pavement 30 feet below. “It was unreal.”

The quake struck with such sudden force that many residents stumbled around dazed in the darkness, groping for shoes, eyeglasses, a flashlight.

At the Park Regency apartment complex in Canoga Park, a two-story apartment building collapsed and crushed a row of 20 cars parked underneath. Rita Cuezada, 20, and her 5-month-old daughter fell through their second-floor apartment to a vacant unit below.

“My body weight fell on her three or four times,” Cuezada said. “I thought she was going to die. I was just praying to God. I thought I was just going to be holding her dead body when it was over.”

In some areas, the earthquake set off a series of other destructive disasters, bursting water mains, touching off fires and sending rocks and mud sliding.

Near Chatsworth, a Southern Pacific train derailed and one of 16 cars carrying sulfuric acid spilled its load. Los Angeles International Airport was forced to temporarily suspend flights. Mobile home parks, with their lightweight construction and often-crowded layouts, proved particularly vulnerable to fires.

At the Tahitian Mobile Park in Sylmar, firefighters watched helplessly as 65 mobile homes went up in flames. Gilbert Neuvenhein was jarred from his sleep by the earthquake and watched helplessly as fires crept near his trailer.

“I woke up. There was a rumbling. The next thing I knew I was trying to reach the door,” he said. “I was frantically trying to open it, but it was stuck. I didn’t have my glasses and I was practically blind without them.”

As flames engulfed the trailers, ammunition stored in one of them began to explode. “I had never seen such a war zone,” said Keith Bedard, a 32-year-old communication technician.

All along Ventura Boulevard, meanwhile, firefighters and Southern California Gas Co. workers were hurrying to plug leaky gas mains. About 7 a.m. a fire crew saw a major leak at Ventura Boulevard and Laurel Grove and urged bystanders to move on: “You’ll be toast if this thing goes up,” a firefighter said.

In Pacoima, thousands of gallons of crude oil spilled into Wolfskill Street east of Laurel Canyon Boulevard when a 10-inch pipeline burst. Soon after, the oil ignited, sending parallel walls of flame racing down the block. The flames consumed two houses and at least 10 cars and scorched dozens of trees along the street. Residents frantically used garden hoses to spray down cars and shake roofs. Several rooftops were burned.

“It just looked like an inferno,” resident Luisa Grimaldo said. “It came just shoosh down both sides. It all just exploded.”

Although the worst damage was in the Valley, other communities were also struggling to dig out from the wreckage.

On the Santa Monica Freeway, seven massive pillars that suspended the freeway over Fairfax Avenue collapsed. The concrete cylinders broke into pieces ranging in size from boulder-like chunks to grains of sand. Their iron reinforcing bars loomed like immense, distended bird cages.

Several buildings in Santa Monica collapsed, others suffered major damage and 12 fires and dozens of gas leaks were reported. In all, 75 buildings were deemed unsafe for habitation by midafternoon--including two large hotels, the Pacific Shores and Holiday Inn Bayview Plaza.

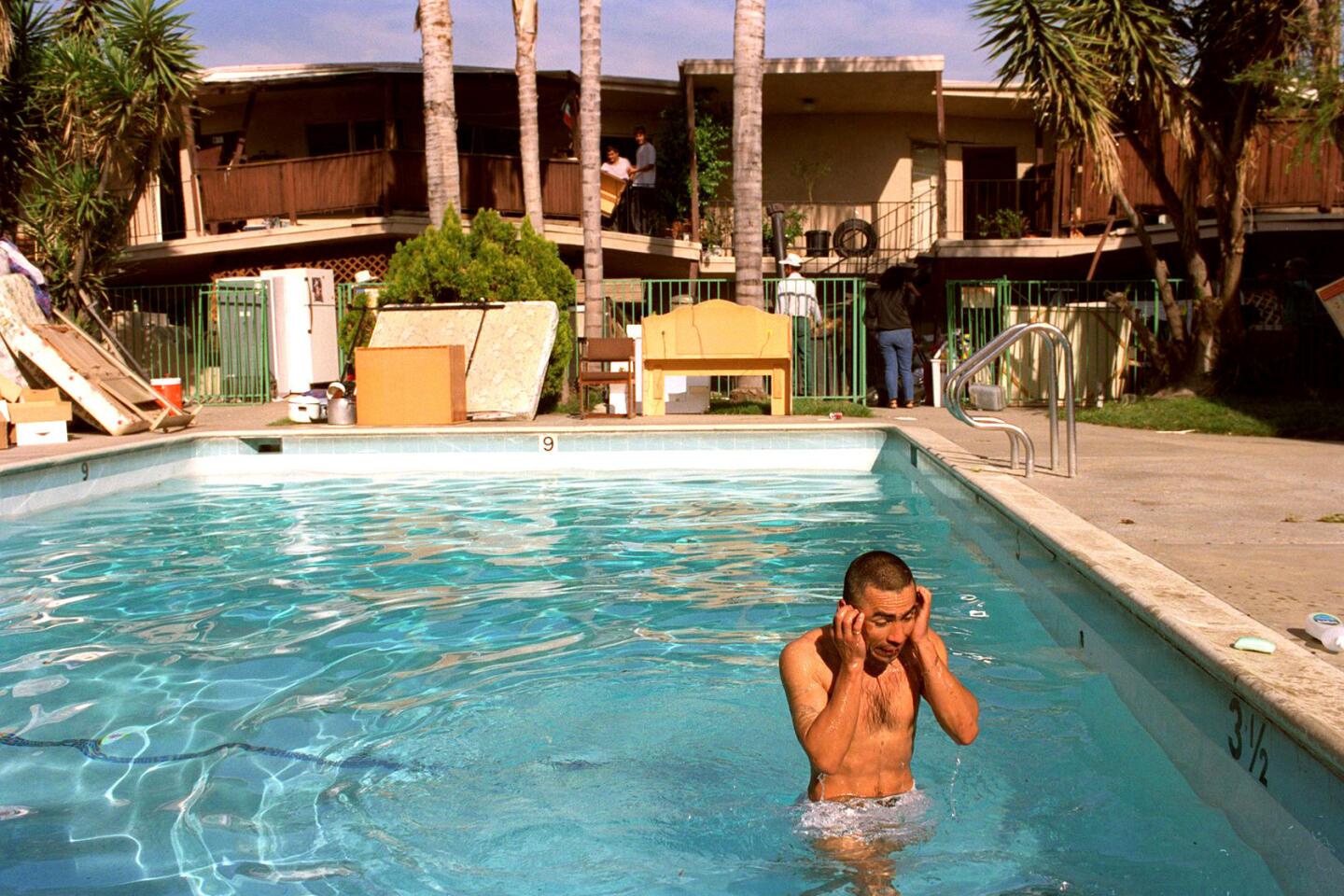

Ignoring the yellow “caution” tape ringing the Sea Castle, a large 70-year-old waterfront apartment building, residents scurried back and forth into the structure to grab whatever belongings they could carry. By 9 a.m the parking lot looked ready for a garage sale as residents tried to cram television sets, microwave ovens and mattresses into their cars.

At Angelo Drive and Mossy Rock Circle on the Westside, the Cooper family sat on their front lawn with their children, Harrison, 4, and Jennifer, 1, as they made plans to go to a hotel. The vigorous shaking had caused the front of their house to collapse. As the quake hit, Michelle Cooper rushed in to pick her daughter up from her crib, where she discovered the baby had stopped breathing.

“I said, ‘She’s dead, she’s dead,” Cooper said. “My husband revived her with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. He said she had something called fright reaction. Usually, I’m OK after an earthquake, but I was shaking because I thought she was dead.”

In Ventura County, the cities of Simi Valley and Fillmore suffered the most serious damage.

At one Fillmore variety store, mannequins were thrown through a plate-glass window and landed in a gruesome pile on the sidewalk. At the Central Market, owner Harnek Sing Behniwal stared at the broken windows, fallen beams and strewn groceries.

“I just don’t know what to do,” he said. “This store was a diamond.”

City officials were particularly upset because the area had recently undergone extensive renovation. “Just when we’ve rebuilt it, we’ve had to declare it a disaster area,” Fillmore City Manager Roy Payne said.

In Simi Valley, across the street from Simi Valley Adventist Hospital, Ted N. Chaffee,a dentist, was perturbed by the earthquake’s seemingly precise aim. Only one of his office windows shattered--the one above his his most expensive piece of equipment, a $50,000 dental imaging system.

‘Come Down and Pray’

Throughout Los Angeles, there were tales of courage--of strangers helping strangers because, as one man said, “it seemed like the right thing to do.” By day’s end, many people owed their lives to that spirit. And many more had been touched by it, as they watched the progress of several daring rescue missions live on television.

Salvador Pena’s story was one of the hopeful ones--a testament to the power of hard work, teamwork and spiritual faith.

Caught during his pre-dawn shift driving a street sweeper along the bottom floor of a three-tier parking garage at the Northridge Fashion Center, Pena talked with rescue workers for more than seven hours as they blasted through slabs of concrete to extricate him.

Firefighters had little trouble locating him because of his loud cries for help, which they could hear even through the mountain of rubble. To reach Pena, rescue workers used jackhammers to drill through two layers of concrete. Then they inserted air bags and wooden blocks to lift a concrete beam off his limbs, giving him oxygen as they worked. Once they cut him out of his vehicle, they carried him on a backboard through eight feet of rubble.

Throughout the ordeal, paramedics remained at Pena’s side beneath the parking deck. “He was in a lot of pain and he kept saying, ‘Come down and pray with me, come down and pray,” said Rey Lavalle, a Los Angeles city firefighter, who spoke with Pena in Spanish.

When a helicopter finally airlifted Pena from the busy mall’s rubble-strewn parking lot and headed to UCLA Medical Center, onlookers cheered and applauded. Late Monday, he was in serious condition with crushed legs and a partially dislocated spine.

“I almost cried--I was elated, we all were,” Capt. Jim Vandell of the Los Angeles City Fire Department said.

Meanwhile, at the Northridge Meadows apartments, firefighters and urban search and rescue squads hunted frantically for survivors of the collapse that took more lives than any other. The three-story complex had folded in on itself, pulverizing many of the first-floor units. All day, rescuers worked tirelessly.

They were right to hope. At one point, as firefighters tramped through the demolished building pounding on floors and calling out to survivors, they heard a man cry out.

Using diamond-bladed saws to chew through concrete and wood, they finally reached the collapsed first floor that had become a tomb. Alan Hemsath, 37, “was just face down--pinned by the whole building,” rescue worker Doug Rogers said. But 90 minutes later, Hemsath--conscious and in stable condition--was freed, prompting applause from onlookers and journalists.

The search continued until nightfall, with rescue workers utilizing sonar equipment sensitive enough to detect even the shallowest breath amid the rubble. Those who had died were left inside the building so rescuers could concentrate on extricating survivors.

‘A Tidal Wave’ of Injuries

The quake took its toll on the young and old, hundreds of whom flooded emergency rooms with maladies ranging from cuts and bruises to heart attacks.

“We’ve seen heart attacks, dislocated bones, lacerations. A lot of blood,” said Toni Regalado, an emergency room admissions officer at Holy Cross Medical Center in Sylmar.

In Los Angeles, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center was receiving “a tidal wave of walking wounded,” spokesman Ron Wise said.

Hospital officials said most of the injuries were caused by people scrambling to protect themselves after the quake struck. Health workers said many cuts, bruises and broken bones resulted when people, in their need to find safety, fell, cut themselves on broken glass, or ran into something in the dark.

In some hospitals, doctors and nurses moved past fallen plaster and broken windows to practice their trade in near-battlefield conditions. Broken water pipes flooded floors, backup generators took over during electrical outages. Ham radios covered for dead telephones.

Henry Mayo Newhall Memorial Hospital in Valencia treated more than 300 people, mostly for cuts and broken bones. The hospital was so jammed that some patients had to wait for up to four hours. People were being stitched up on stretchers in the hall.

The doctors at Henry Mayo were slightly red-eyed. Iodine was on the floor, spilled off wounds where it had been liberally applied.

“People are running on adrenaline,” said Henry Mayo Administrator Duffy Watson. “We are overwhelmed. We need to get our staff rested.”

At the Granada Hills Community Hospital, doctors, nurses and volunteers operated a makeshift emergency room in the shadow of the Kaiser Permanente clinic and office building which collapsed next door.

With heads bandaged and blackened blotted blood dried around their cuts, quake victims sat in the sun waiting. Meanwhile, a cadre of workers applied temporary bandages and tried to ease their pain.

Brian Wills, 23, of Canoga Park was among those waiting. He suffered a deep cut on his shoulder climbing out his first-floor apartment window. “I jumped out and started running down the street. . . . I definitely panicked,” he said.

An unprecedented 600 to 700 patients were evacuated from earthquake-damaged hospitals. Metropolitan Transportation Authority buses and helicopters were pressed into duty to shuttle patients out of the crippled hospitals.

The largest evacuation occurred at Olive View Medical Center, where all the patients in the 377-bed hospital were transferred because of serious water damage, gas leaks and power outages. The hospital was built on the same site where another county hospital was destroyed in the 1971 Sylmar earthquake.

Dozens of other hospitals in the area also suffered enough damage to force evacuations or to prompt officials to move patients in large numbers from one floor to another.

Among the hospitals forced to close were Holy Cross Hospital Medical Center in Sylmar and the Sepulveda Veterans Administration Hospital in North Hills.

But it was not all tragedy.

A Torrance woman was in the final moments of giving birth early Monday when her room at Torrance Memorial Medical Center began shaking.

Wendy Gonzales, 37, gripped her husband’s hand hard as the walls shook, medical supplies clattered to the floor and her daughter’s head began to emerge from the birth canal.

“It all happened at the same time,” said her husband, Eddie Gonzales, 35. “Everything started shaking, things started falling. . . . I heard a lot of rattling going on, and a lot of screaming.”

Courtney Gonzales, 7 pounds, 6 1/2 ounces, was born at Torrance Memorial Medical Center at 4:45 a.m.

‘Holding My Heart’

Farther from the epicenter, where the shaking was less severe, emotional trauma eclipsed physical danger. The quake left people disoriented, bewildered and, in the case of one young man, literally dazed.

John Bryce, 16, was hit in the head by a 32-inch television as he slept on the floor of a friend’s Simi Valley home.

“It just fell on my head and knocked me out,” Bryce said as he waited for a gash above his nose to be stitched. “When I woke up, there was a television in my lap.”

But with humor, creativity and a little homespun philosophy, people set about trying to cope. Life would go on, they said. And maybe next time they’d be a little better prepared.

“I never liked the bathroom anyway,” said a 38-year-old Sherman Oaks banker after a neighbor’s chimney toppled into his bidet.

Jon Lalanne, a 32-year-old bartender in Malibu, is now calling his apartment on Las Flores Canyon Road simply “the disaster capital of the world.”

“My whole apartment building was doing the hula,” he said, demonstrating with his hand the undulating motion he saw and felt. His biggest complaint, however, was gastronomical, not geological.

“I’m dying for a cup of coffee, man, and there’s none to be had,” he said.

Many people sought comfort in numbers. In Santa Monica, residents transformed the median of San Vicente Boulevard from its usual function--a jogging path--to a makeshift meeting place and parking lot. From 7th Street to the ocean, the grassy strip resembled a pre-dawn block party as apartment dwellers--some still in robes, others wrapped in blankets--gathered to compare jolt notes. Fearful that underground garages would collapse, some people left their cars in the median as well.

Necessity also brought people together. In Malibu, people waited in line to buy bottled water, Rice Krispies, London broil--whatever was available. In eastern Ventura County, lines at hardware and general supply stores stretched out the door as jittery residents stocked up on flashlights, batteries, and repair materials for broken pipes and generators.

“Someone came by my house and said Sears was open, and it’s a good thing,” Dirk White, 36, a Thousand Oaks resident, said as he waited to buy repair materials at Sears department store. “My hot water heater busted. Where (else) do you get parts for that at a time like this?”

Joan Tang of Camarillo was standing in a similarly lengthy line to buy a better radio than the small transistor model she had at home. The earthquake had scared her, she said, and had taught her a lesson.

“It took me three hours to calm down,” Tang said. “I need to be prepared. It took an earthquake like this to finally admit it. I was holding onto my heart.”

Sleeping Under the Stars

Haunted by memories of what the previous night had brought, a nervous city greeted Monday’s sunset with one eye open. As the ground rolled and rocked with aftershocks--86 of them in the first 17 hours after the quake--it was difficult to believe the truth: that the worst was most likely over.

Floods, fires, riots--Los Angeles had survived them all. But this felt more fundamentally unsettling than anything that had come before. So, while curfews were put in place to make neighborhoods relatively free from crime, no one was taking their safety for granted.

Long before nightfall, the displaced and the distressed flocked to shelters or the streets, planning to sleep on gymnasium floors or back seats of family sedans. Many simply camped out in their yards.

In Koreatown and Pico-Union, where many residents spent the day on porches and lawns, there were no plans to return indoors after dark. “We’re going to sleep outside tonight,” said Pilar Canela, 10, who lives with his family in a Koreatown apartment. “It’s kind of dangerous to do that, but we’re more scared of another earthquake.”

In the Santa Clarita Valley, about 150 people gathered on the green cots at a Red Cross evacuation center set up in the gloomy, unlighted gymnasium of Henry Newhall Park. Most had been evacuated from the Orchard Arms Senior Complex, a residential development that developed a gas leak.

Outside, the scene was almost festive as about 500 Latino families set up camp with tents and barbecues. Ricardo Provincia, 23, set up three tents to house the 14 members of his extended family through the night.

“There are cracks all over our apartment, which is on the second story,” Provincia said. “It’s scary in there. We thought we’d be a lot safer here, tonight.”

For some, like Poppy Weisberg, sleep would be difficult anywhere. Weisberg, 79, was among 150 people who sought shelter at Sylmar High School, where the Red Cross had set up a shelter. She sat in a flowered nightgown on a borrowed cot and recounted how she had come to be there.

Weisberg had narrowly escaped injury when her mobile home in the Los Olivos mobile home park burned. If not for her neighbors, who pulled her through her mobile home’s front door, she might not have survived, she said.

“You could hear the gas and I kept yelling, ‘Turn off my gas!’ ” she said.

But it was too late. After her mobile home and others went up in flames, she returned to see what was left.

“It took a lot for me to go back and see what the damage was,” she said, choking back tears.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.