South L.A. was promised a Target. Millions of dollars later, it has a vacant lot

After 12 years, a proposed site for a South L.A. shopping complex remains vacant.

The plan was to deliver middle-class amenities — Target, a Ralphs supermarket, sit-down restaurants like Chili’s — to a section of Los Angeles that had long suffered from under-investment.

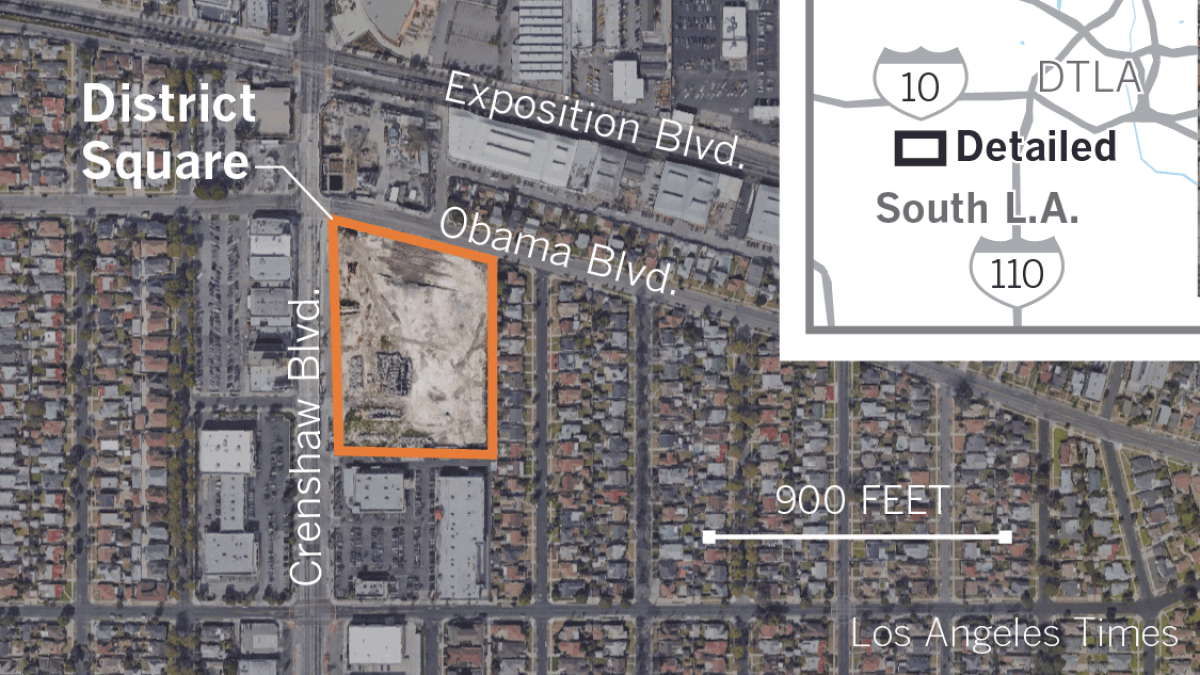

The proposed shopping center known as District Square would be a great catalyst in the center of the city, revitalizing Crenshaw Boulevard and showing what was possible in disadvantaged neighborhoods, backers said. Councilman Herb Wesson embraced the project, championing a lucrative package of loans and grants to get it built.

“We have to bring in the best of the best,” Wesson said in 2010, the year the shopping center was approved.

Nearly a decade later, the District Square site sits vacant, a symbol of promises made and later abandoned.

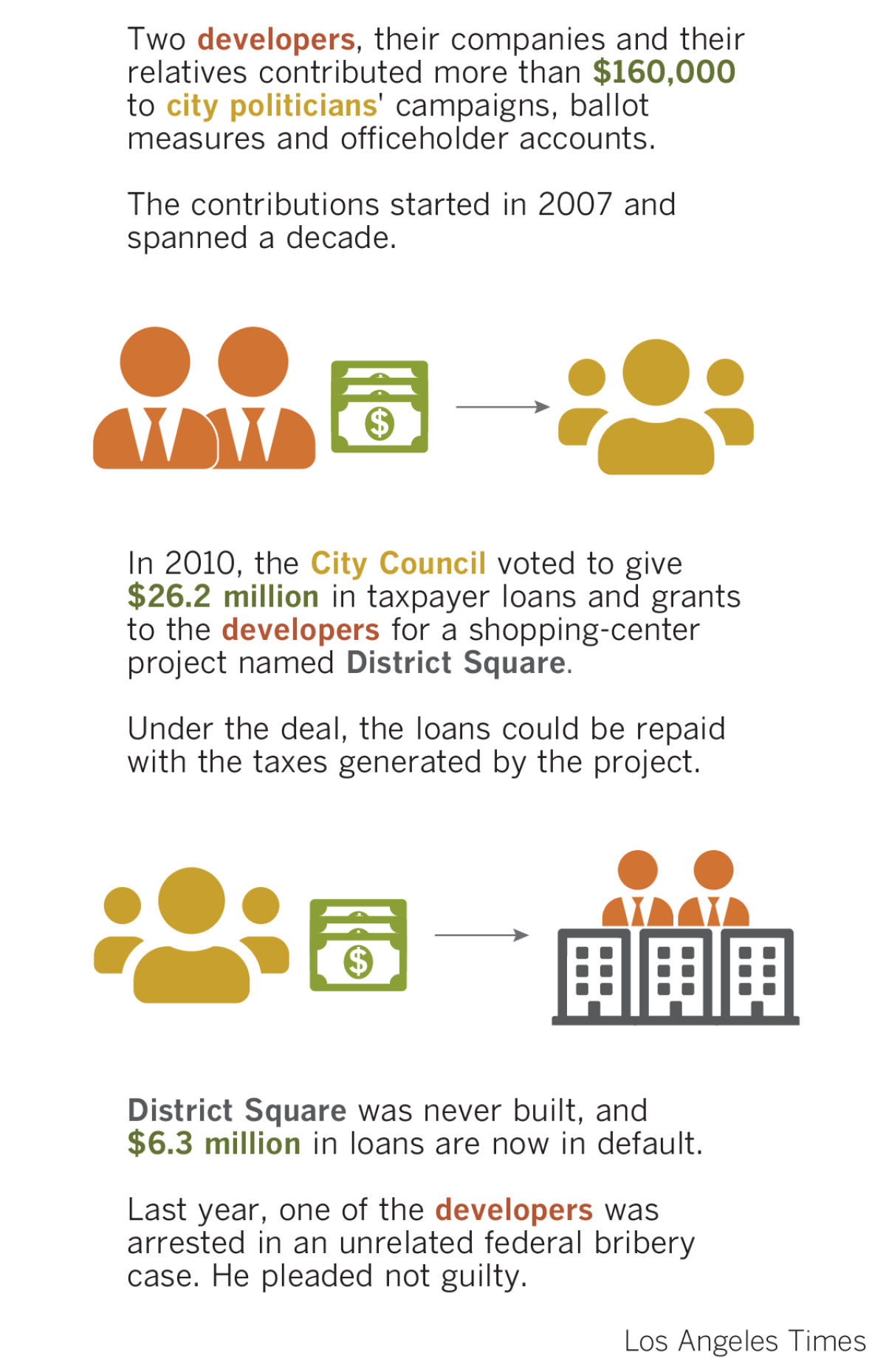

None of the 600 jobs have materialized. The project has $6.3 million in federal loans that are in default, according to the city’s Economic Workforce Development Department. And Arman Gabay, the Beverly Hills businessman who proposed the project, has been charged with bribery in a case involving county leases. He has pleaded not guilty.

Wesson, now council president, repeatedly went to bat for District Square, even as the developers and their companies donated to his campaigns, his causes and his political allies. He worked to shore up the project as others at City Hall raised alarms. At one point, he had an aide working on the project who happened to be Gabay’s brother-in-law. Wesson later said he was unaware of the connection at the time.

Still, after years of rescue attempts, Wesson signaled in recent weeks that he has lost patience.

“The developer should get out of the way, so the city or another developer can deliver a mixed-use project the community wants and expects,” his spokesman said in an email.

Gabay, who has also gone by the name Gabaee, declined to comment. His brother and longtime business partner, Mark Gabay, did not respond to inquiries.

In an email to Wesson’s office last year, a consultant for the developers said they are pushing ahead with a dramatically reworked project, now seven stories instead of two, after years of “broken promises.”

“Let me state for the record, there has never been any intention to deceive, delay or misrepresent to your office or to the community our development plans and timing for the District Square development,” the consultant wrote in June 2018.

Seven default notices

For much of its history, District Square was the subject of a behind-the-scenes tug-of-war between Wesson, who represents the area, and Jan Perry, who until December ran the agency that issued the city loans for the project, according to correspondence obtained by The Times.

Perry’s agency sent District Square seven default notices between 2015 and 2018, repeatedly pointing out that the developers had failed to build the shopping center. Wesson, on the other hand, searched for funds as the developers fell behind on their obligations.

The two political veterans, adversaries for nearly a decade, are now running against each other for a seat on the county Board of Supervisors.

Perry, a former city councilwoman, said she pushed for the city to foreclose on District Square and seize the site, only to have those efforts opposed by aides to Wesson and Mayor Eric Garcetti.

“I never wavered,” she said. “But I was not the ultimate decision maker in this process.”

Wesson disputed Perry’s assertions, saying she never met with his staff to discuss the issue. He acknowledged his various efforts to salvage the project, saying it’s not been easy bringing new development to the Crenshaw area.

“When you invest so much time, you’d like to see a result,” he told The Times last year.

Garcetti aides defended their handling of the project, saying any move to foreclose could have led to a drawn-out legal battle. The better strategy, they said, is the one they have been pursuing: working with the developers on a redesigned project that offers 573 apartments and a reduced amount of retail space.

Once the planning department gives its approval, a decision expected by the end of the month, District Square should have no trouble attracting investors and clearing up its financial issues, said Steve Andrews, an economic development aide to the mayor.

“The market will deliver something to this site,” he said.

One neighbor said the city’s push to build District Square made things worse. With taxpayer money, the developers razed a Ralphs supermarket without providing a replacement.

“Now it’s just an empty field,” said Lori Higgins, who lives nearby.

A lucrative deal

Gabay has long been active in L.A. politics. He, his relatives and his family’s companies have given more than $160,000 to city candidates, officeholder accounts and ballot measure campaigns since District Square was first proposed in 2007, according to fundraising reports.

Gabay’s plan for District Square called for the demolition of a shopping center that housed the Ralphs, a dry cleaner and other businesses. Under the proposal, it would be replaced with a structure three times larger at Crenshaw and Rodeo Road — now Obama Boulevard.

Wesson and his colleagues approved the project in 2010, providing $26.2 million in federal grants and loans. The developers also received permission to repay their loans using tax revenue generated by the new shopping center — money that would otherwise flow to city coffers, according to a city analysis.

The developers tapped only a portion of their federal loans, acquiring the site and moving out the existing businesses. Yet soon they asked for more help.

Wesson responded in 2012 with a plan for lending District Square an additional $6 million. The 30-month “float loan” would keep the project on track, he said, while the developers locked down their private financing.

Instead, things got worse. Target dropped out. District Square did not qualify for the tax credits needed to finance the project. Troubled by the lack of progress, Perry’s agency sent its first default notice in January 2015, pointing out the developers had missed their deadline for starting construction.

“The city believes this breach is not curable,” Perry wrote.

Perry had been at odds with the Gabays before. While she was on the council, one of their companies sued the city over a redevelopment project in her South L.A. district.

The Gabay brothers had friendlier relations with others at City Hall.

In the two years leading up to their project’s first default notice, the Gabay family and one of their companies, Excel Property Management, donated nearly $55,000 to city office holders, campaigns and political causes — nearly half of it to Wesson’s unsuccessful push to hike the city’s sales tax.

Weeks after the first default notice arrived, Excel donated $25,000 to a 2015 ballot campaign, also backed by Wesson, to move city elections to even-numbered years. The company also gave $10,000 to a committee backing the re-election of Councilman Jose Huizar, a close Wesson ally. During the campaign, Wesson had described Huizar as his best friend on the council.

Edward Johnson, Wesson’s spokesman, said his boss did not ask Excel to give to the pro-Huizar committee. Wesson “cannot recall” whether he asked Excel to donate to the ballot campaigns, Johnson said. The aide said donations from the Gabays and their companies had no influence on the city’s handling of District Square.

Huizar won re-election and voters approved the change in election dates. Three months later, Perry’s agency sent another default notice, saying District Square’s float loan had come due.

With the deadline looming, Wesson’s team focused on a possible lifeline: an $8-million loan from the city fund that collects parking meter revenue.

An in-law steps in

The official who worked on the proposed parking loan was Jordan Beroukhim, a Wesson aide who happened to be Arman Gabay’s brother-in-law. In June 2015, Beroukhim sought to have the proposal bypass the council’s transportation committee, which vets the use of such funds, according to emails obtained by The Times.

Such a maneuver would have sent the proposal directly to the council for an up-or-down vote. But Beroukhim encountered an obstacle in Ellen Isaacs, then a staffer with Councilman Mike Bonin, who heads the committee.

Isaacs told Beroukhim she was concerned with the lack of analysis on the need for the loan. “It just feels like a more substantive conversation is warranted,” she wrote, adding minutes later: “Is there a particular rush on this matter?”

“This project was approved in 2010,” Beroukhim responded. “We have been sitting on it for 5 years.”

The loan proposal was eventually scrapped. Wesson later told The Times he wasn’t aware at the time that Beroukhim had a familial connection to Gabay. Once an aide learned of it, Berkoukhim was moved off of District Square out of “an abundance of caution,” Wesson said.

Beroukhim, contacted by The Times, referred questions to Wesson’s spokesman, who declined to answer on his behalf.

Another lifeline

Wesson soon took another stab at rescuing the project. In a July 2015 letter, he asked a staffer in Perry’s agency to delay default proceedings until the city had a new plan for closing the project’s financial gap.

The developers also asked for more time, saying they had attracted Home Depot and needed to rework the project. Perry refused, saying in a letter that her staff had discussed repayment with the developers “numerous times.”

Wesson landed on a solution: the city would pay off the loan’s $2.1-million balance by tapping federal funds that were not immediately needed for another project. The city would execute a new float loan worth the same amount for District Square, restarting the 30-month clock.

The solution was offered on the council floor in October 2015 and approved the same day. Before long, District Square was in trouble again.

Federal officials informed the city in July 2016 that $1.9 million in funding for District Square — money given to “shovel-ready” projects that could pull the nation out of the 2008 recession — needed to be repaid. The shopping center, which was supposed to open that year, had not been built.

Perry sent two more default notices. The developers, through their attorney, fired back with a letter blaming Metro, which had begun building a $2-billion light rail line on Crenshaw.

Construction barriers had made it difficult to attract tenants, the lawyer wrote. Although the developers could have demanded compensation from Metro, they had decided to be a “good corporate citizen,” he said.

Months later, Gabay agreed to repay the Obama-era recovery funds and submit new plans for District Square. The redesigned project would be primarily residential, but also offer a Smart & Final and a Ross Dress For Less.

“This is definitely good news,” wrote Andrews, the Garcetti aide, in a May 2017 email. “A major project at a Crenshaw line station is ready to move forward!”

The euphoria was short lived.

Optics and audits

Three months later, Garcetti’s aide was informed that the Gabay brothers were at odds, according to correspondence obtained by The Times. Work on the permits had stopped and the deadline for the second 30-month loan was approaching. Officials were no longer sure the new project, with much less retail space, would deliver the 600 jobs required under the original loan package.

In an email to a Wesson aide, Andrews worried about damaging audits and the “optics” of having one company receive so much federal money while failing to produce.

“And now that they have filed for a project that will NEVER create the required jobs … it will be even more embarrassing to leave all the public funds in place,” he wrote.

In February 2018, Perry sent District Square three more default notices. Three months later, Gabay was arrested on suspicion of bribery. Prosecutors accused him of making illegal payments to a Los Angeles County bureaucrat in exchange for a government lease.

Gabay filed the application for the reworked District Square last summer and, weeks later, entered a not guilty plea. He turned in more paperwork in January.

Despite all the setbacks, Andrews remains optimistic. The developers have a vacant site and a new set of plans, the Garcetti aide said. Within weeks, city planners should render their decision on the new project.

“Those are huge steps,” he said, “in making a project ready to go.”

L.A. Times Today airs Monday through Friday at 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. on Spectrum News 1.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.