Protests continue after LAPD releases video showing moments before fatal police shooting

The Los Angeles Police Department released this surveillance video of Carnell Snell Jr. just prior to the 18-year-old being shot and killed by police on Saturday.

In recent months, law enforcement leaders around the country have found themselves backed into the same corner following controversial police shootings captured on video.

Chiefs in Fresno, Charlotte, N.C., El Cajon and other cities initially refused to make the recordings public. But after days of protests and continuing demands for transparency, police leaders relented and released the video in the hope of reducing tensions and validating their accounts of what happened.

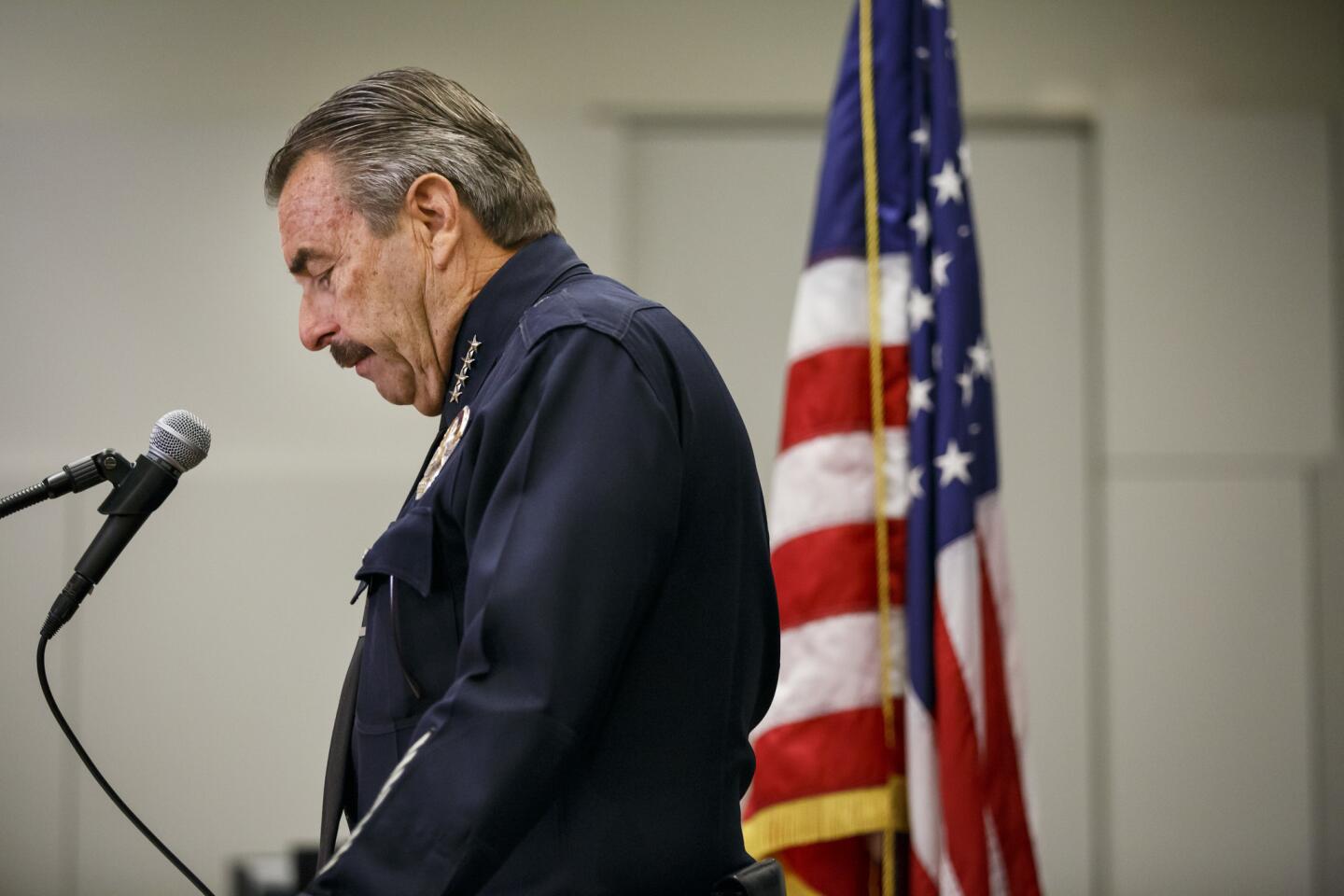

Faced with criticism over the fatal police shooting of a black 18-year-old this weekend, Los Angeles Police Chief Charlie Beck found himself in a similar position and opted on Tuesday to release surveillance footage that showed Carnell Snell Jr. holding a gun moments before he was shot.

Beck, generally a staunch advocate of keeping such videos confidential, said he acted out of concern for public safety as well as to correct claims by some who knew Snell who said that the teen didn’t have a gun.

“My huge concern is that the dueling narratives further divide the community,” he said.

The move underscored the challenge law enforcement agencies confront in trying to keep video of police shootings confidential during a time of heightened public scrutiny of how officers use force, particularly against African Americans. By releasing videos in these high profile cases, police departments have set up the expectation that they will make recordings public in the future.

Police leaders nationwide have long argued that the release of such videos can imperil investigations and violate the privacy of people captured on body or dashboard camera recordings. But proponents of making the videos public say recent events show that the recordings can be made public without endangering investigations and that departments should not be cherry picking which videos to release if they want to regain trust in minority communities.

“It’s clear that keeping video confidential isn’t going to work. It undermines public trust more than it advances it,” said Peter Bibring, director of police practices for the ACLU of Southern California. “Body camera footage or other video doesn’t provide transparency if the public never gets to see it.”

Some law enforcement experts were critical of police leaders for giving in to protesters by releasing video they otherwise would not.

“What you’re seeing is basically a policy of appeasement,” said Jon Shane, a professor at the John Jay School of Criminal Justice in New York City and a former police captain in Newark, N.J.

Shane said state legislatures should decide the rules for making recordings public. In California, lawmakers have repeatedly failed to draw up statewide policies on the issue.

In Los Angeles, Police Commission President Matthew Johnson said Tuesday that he is pushing ahead with a plan to reexamine the LAPD’s general practice of withholding videos from the public. Johnson said it was important to find a “level of transparency that makes sense in today’s environment” while also considering potential legal constraints and the challenges of reviewing the vast amount of video the LAPD collects.

Snell was shot Saturday afternoon after he ran from a car that officers thought could have been stolen and reached an area between two houses with a closed metal gate that had “somewhat-transparent” mesh, Beck said Tuesday. Snell, the chief said, turned with the gun in his hand.

Officers felt Snell was an “imminent threat,” Beck said, and one fired three shots. Snell hopped the fence and again turned toward the officers, Beck said, still holding the gun. Police fired an additional three rounds.

Some residents questioned the police account, including whether Snell had a gun.

The decision to make the video of Snell public followed lengthy conversations among Beck, Johnson and Mayor Eric Garcetti, according to interviews. All three were concerned with the competing narrative about the killing.

The video came from a nearby business and shows a young man in a blue sweatshirt, identified by police as Snell, running through a strip mall and behind parked vehicles, holding what appears to be a gun in his left hand. The man crouches and appears to tuck the handgun into his sweatpants before running out of view of the camera. Moments later, a police officer is seen running in Snell’s direction.

Despite the decision to release the recording, Beck said the department had yet to decide if it would release video from body cameras worn by officers in a second deadly police shooting, which took place in South L.A. on Sunday. Beck has said that the video clearly refutes reports that some of the shots were fired when the man was on the ground. But releasing that video, he said, could set a standard for the LAPD in terms of complying with public records requests for such recordings.

Beck cited a number of reasons why he was hesitant to release body camera video, including concerns about the graphic nature of some recordings and the time it would take to sort through an enormous volume of video to comply with public records requests. But, the chief said, he was also worried frequent release of videos could violate the privacy of members of the public captured in recordings.

“I know, as a lifelong police officer, that I see people on the worst day of their lives,” he said. “People shouldn’t feel like when the police come to your house that what’s happened to you is going to be splashed all over the Internet.”

The release of videos in other parts of the country has sometimes failed to fully answer questions over shootings.

Police in Charlotte released footage of the fatal shooting of 43-year-old Keith Lamont Scott last month after protesters swarmed the city’s downtown area, damaging several office complexes, but the recording left unclear whether or not Scott was armed.

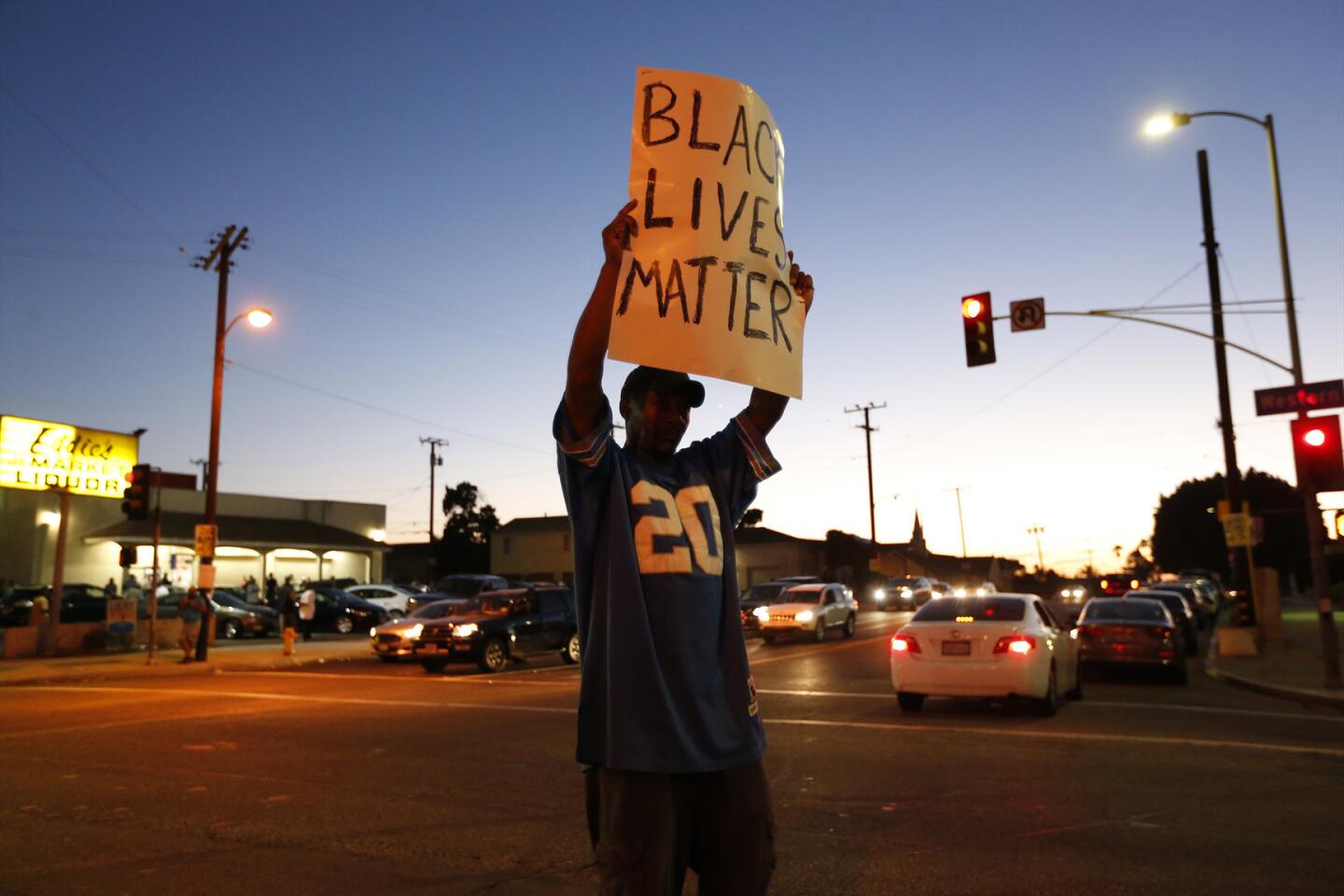

In Los Angeles, the video connected to Saturday’s shooting drew mixed reactions from Snell’s loved ones and protesters who packed into the weekly Police Commission meeting.

Snell’s great-aunt, Carlena Hall, said she wished the LAPD had informed her family ahead of time before releasing the video but said the recording clearly showed he had a gun.

“I don’t care if it hurts the LAPD or me, the truth needs to come out,” she said.

But the video doesn’t show the moment that the shots were fired, she noted. And she disputed the police account that Snell was shot when he turned toward officers while holding the firearm, saying he was no threat. She said Snell was mentally ill but did not elaborate. She said he had been arrested several times before and had run every time out of fear.

“That gun was never meant to be a threat to the Police Department,” Hall said.

At the commission meeting — where protesters booed Beck as he walked into the room — activist Melina Abdullah accused the department of trying to “assassinate” Snell’s character after his death. She and others called for the LAPD to make videos of other police shootings public.

“If they can release that video, they can release every damn video,” said Abdullah, an organizer with the Black Lives Matter movement.

Frustrations boiled for many in the audience, including Lisa Simpson, whose 18-year-old son, Richard Risher, was fatally shot by LAPD officers in July. Simpson has regularly attended the commission’s meetings since her son’s death.

“If I start killing your officers the way you killed my kid, is that equal?” she asked Beck. “I say an eye for an eye.”

The LAPD said Risher shot and wounded an officer before he was killed.

In an unusual move, two police commissioners, Cynthia McClain-Hill and Shane Murphy Goldsmith, remained behind to talk with the audience after the board adjourned to go into closed session. McClain-Hill urged the crowd to keep up the fight for police transparency, but also expressed concern over some of the remarks.

“You make me want to cry when you applaud the idea that we should take up arms and shoot others,” McClain-Hill told the audience, which immediately erupted in jeers and criticism.

“But that’s what they’re doing to us!” one woman replied.

When Beck was asked at his news conference about Simpson’s remarks, the chief sighed.

“I understand that she grieves, but the Los Angeles police officers have a very dangerous job,” Beck said, adding that he did not believe her comments rose to the level of a crime but that police would review them.

Beck acknowledged the anger surrounding the weekend’s shootings and said he believed some of the reaction has been compounded by other police killings around the country.

“We have all seen police-involved shootings that defy justification in other municipalities. I have seen them where I am at a loss to understand why,” he said. “I think that affects what happens on the streets of Los Angeles.”

Times staff writer Veronica Rocha contributed to this report.

For more breaking crime and police news, follow us on Twitter: @katemather, @JamesQueallyLAT and @JosephSerna

ALSO

El Cajon police and the fight over a video

UPDATES:

8:25 p.m.: This article was rewritten with additional references to police shootings in other parts of the country and comments from Bibring and Shane.

1:50 p.m.: This article was updated with additional comments from Police Chief Charlie Beck and more details about the Police Commission meeting.

11:50 a.m.: This article was updated with additional information from the Police Commission meeting.

12:05 p.m.: This article was updated with reactions to the video and comments made during the L.A. Police Commission’s meeting.

8:45 a.m.: This article was updated with details about the video’s release.

This article was originally published at 8:15 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.