Churches answer call to offer immigrants sanctuary in an uneasy mix of politics and compassion

Reporting from Oxnard — The protesters screamed into bullhorns every Sunday for a year after Liliana Sanchez de Saldivar moved into the United Church of Christ in Simi Valley.

They told her to go home.

It was 2007 and U.S. immigration agents had shown up at her home in Oxnard to take her away. But when they saw the baby boy on her arm, they told her she had five days to get ready for a free ride across the border to Tijuana.

Instead, she packed her belongings and headed to the home of a church deacon in Sierra Madre, who eventually got her settled in the Simi Valley church parsonage while immigration advocates took up her cause and her case garnered widespread attention.

Ten years later, President Trump’s promise of a crackdown on illegal immigration has congregations across the state and country again mobilizing to shield immigrants from deportation.

In a deep blue state where many oppose Trump’s rhetoric on immigration, churches have emerged as a key part of the resistance effort. It’s part politics and part religious duty.

Church sanctuary for those in the U.S. illegally began in the 1980s in response to the plight of Central Americans seeking political asylum, and has continued amid various immigration crackdowns.

The movement offers religious institutions and their members a chance to help those they feel deserve to stay. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has a longstanding policy of generally avoiding enforcement activities at “sensitive locations” such as churches, hospitals and schools.

The number of churches willing to offer sanctuary has doubled to more than 800 since Trump’s election and is still growing, said the Rev. Noel Andersen, national grassroots coordinator at Church World Service, which works with and tracks the loosely organized movement.

Driven by President Trump’s immigration policies, congregations across the state are mobilizing to shield immigrants from deportation.

The goal of sanctuary is for ICE to grant the immigrant a stay of deportation. Afterward, an attorney can determine whether the person qualifies for some type of legal status, such as asylum or a “U” visa for victims of crime.

The sanctuary church movement is spreading to places that traditionally did not offer sanctuary, Andersen said, like Grand Rapids, Mich., and Twin Cities, Iowa.

At the Unitarian Universalist Church of Fresno, the Rev. Tim Kutzmark hopes his congregation will agree to host immigrants. The church’s board voted last month to do so, but needs affirmation by the congregation to move forward.

Kutzmark said the church could comfortably house a whole family. It could be the first church in Fresno to shelter immigrants since the 1980s.

“We’re lucky because this used to be a house,” he said earlier this month, showing off a multipurpose room with a piano and whiteboard that could, with the addition of a bed and blinds, easily become a living space. Next door is a bathroom with a shower. The property also has an industrial kitchen, washer and dryer and a community garden with rows of strawberries, chard and artichokes.

In the 1980s, the congregation supported Central American families that had taken refuge in Fresno after fleeing civil war and death squads. But some members so objected that they signed forms — in case the church got in trouble — stating that they had not taken part.

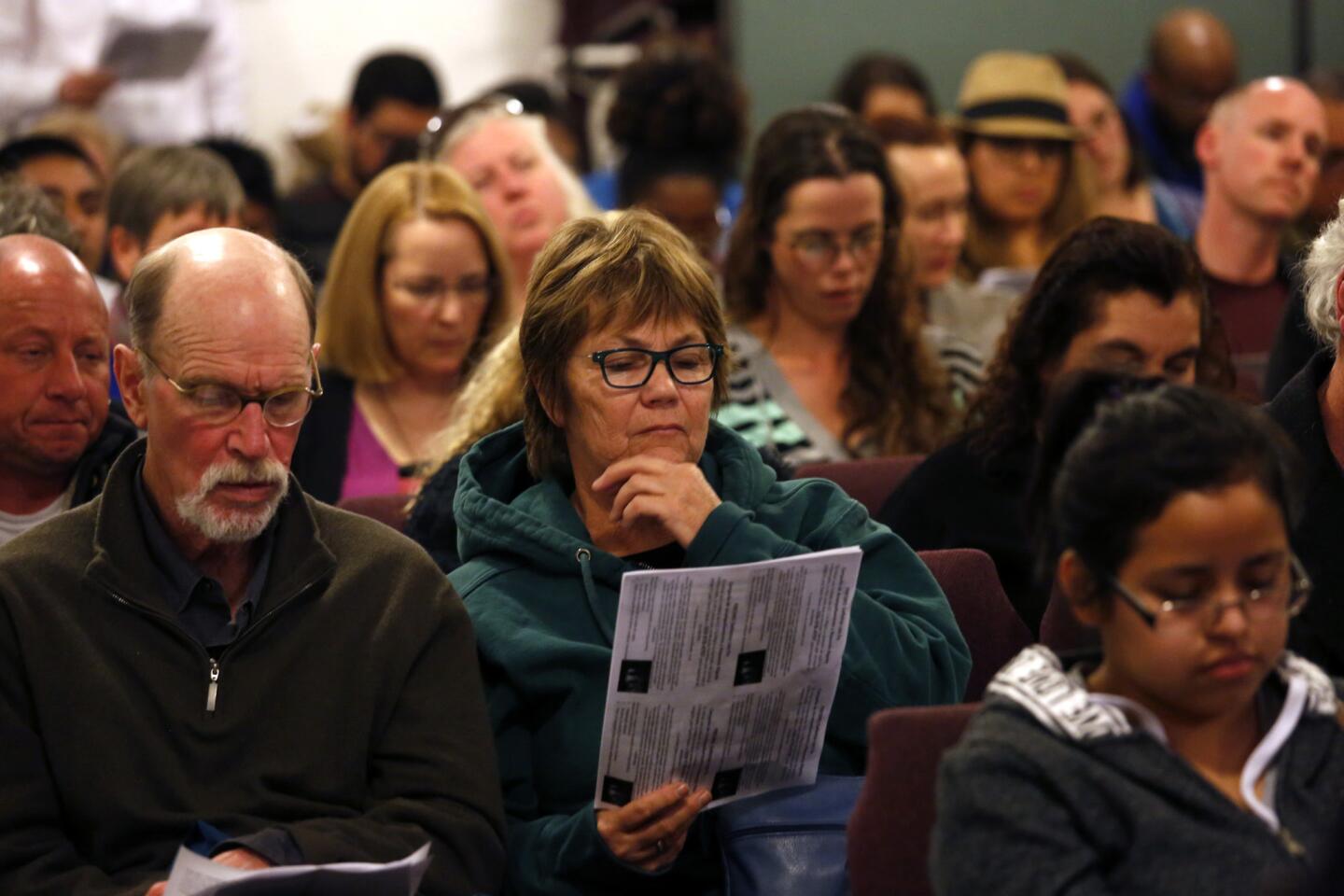

Around 75 people, including Kutzmark, recently packed into a small Baptist church in Fresno to learn how to protect immigrants detained by immigration agents. Faith leaders in more liberal areas of the state, including Los Angeles and Berkeley, have already conducted similar volunteer events.

Kutzmark’s church is affiliated with PICO, a national network of faith-based community organizations and congregations. PICO leaders estimate their congregations could immediately house 150 people in Los Angeles County alone.

Faith leaders say an increasing number of congregants are also offering their own homes as sanctuary. They question whether ICE will continue to honor its policy against detaining people in churches and count on private homes being protected by the 4th Amendment against unreasonable search and seizure.

The Rev. Alexia Salvatierra, a Lutheran pastor in L.A., who co-founded the movement, said that a generation ago immigrants stayed in churches when they first arrived before being transferred to congregants’ homes.

But the situation then was different. Those in sanctuary had just arrived in the country with nothing. Salvatierra said they would go on to receive asylum or, more often, be resettled in a new community where immigration agents were unaware of them. After thousands were deported, Congress passed legislation in 1990 allowing Central Americans to receive temporary protected status.

“It made perfect sense for them to stay either in churches or in people’s homes who were part of churches for a period of time while we figured out what was going to happen to them or where they would go,” she said.

By 2006, the circumstances for many facing possible deportation had changed, Salvaterria said. “People already had homes, they had jobs, they were completely integrated into the community,” she said. “The last thing they wanted to do was live in a church forever or even for a period of time.”

During the second wave of the movement, sanctuary was used to score public relations points in the drive to achieve immigration reform. But leaders of the movement aren’t sure whether that strategy will work with the new administration.

Leaders say they don’t know if or how the Trump administration will apply prosecutorial discretion, the authority that allows immigration agents to decide whether to pursue an immigrant for deportation.

“My guess is they’re going to make an example of a church,” said Kutzmark, the Fresno pastor. “It’s to scare people. But going after a church in a way sends a message that no place is safe.”

Jessica Vaughan, director of policy studies at the Center for Immigration Studies, which favors less immigration, said she doubts that will happen.

“I don’t expect that officers will start storming church basements or schools to make arrests,” she said.

Vaughan cited the U.S. Code against knowingly or recklessly transporting or harboring an immigrant in order to avoid detection. Violating the law is punishable by fines and prison time.

“If that person goes on to commit some harm to someone or the community, that could be devastating to the parish and discredit the entire sanctuary movement,” she said.

In 1986, a Presbyterian minister and seven other activists were convicted of charges stemming from providing sanctuary to Central Americans and served probation.

Andersen, of the Church World Service, said there have been 22 public cases of immigrants taking sanctuary in churches since 2014. Of those, he said, 15 received relief from deportation and seven remain in sanctuary, awaiting a decision from immigration officials. The most recent involves Emma Membreno-Sorto, a Honduran grandmother who has been living at an Albuquerque church since last week.

In Sanchez de Saldivar’s case, advocates told her they would make sure she would never be separated from her husband and four children — all of them American citizens.

Congregants from area churches of various denominations helped care for Sanchez de Saldivar, now 38. Someone was with her in the four-bedroom, two-bath former parsonage at all times.

The church covered her living costs and some groceries. Church leaders also received a $40,000 bill from the city for police presence during the protests, thought it was later withdrawn.

Every three months, the 80 or so congregants voted to continue helping her. After Sanchez de Saldivar left the church in 2010, an interfaith coalition met with her monthly and accompanied her to meetings with ICE.

A native of Michoacan, Mexico, Sanchez de Saldivar was detained in 1998 while attempting to cross the border, but secretly entered the country a few weeks later. She met her future husband, Gerardo Saldivar, on the first day of her job at a corn-packing facility near Oxnard.

Soon after their wedding the next year, the couple began the process of applying for her to become a permanent resident like her husband. A “notario” they had hired told them her earlier border detention would not be a problem. In Latin America, “notarios publicos” are qualified lawyers. In the U.S., people posing as notarios lack licenses and training and prey on immigrants.

Her husband became a citizen in fall 2002 and about a year later she was granted a one-year work permit. Then in 2005, the couple encountered a roadblock to Liliana’s residency petition: The border detention that the agent had assured her would not be a problem had made her ineligible for permanent residency.

After taking shelter at the Simi Valley church in 2007, Sanchez de Saldivar stayed busy caring for her infant son Pablo.

She left just five times, all for doctor’s appointments after she got pregnant during her last year there. She missed her oldest son’s first Communion, her uncle’s funeral and countless events recognizing her children’s achievements in school. She’ll never forget the look on her daughter Susy’s face when she asked, “Mommy, why are they shouting, ‘Deport Liliana?’”

Immigration officials finally agreed to halt her deportation in 2010 and she moved out of the church, back to her family. Five years later, Sanchez de Saldivar got a green card.

The amount of time she spent in the church sanctuary — three years — was unusually long. But immigrant advocates say some people are now preparing to remain in sanctuary even longer. Maybe until Trump leaves office.

Times staff writer Brittny Mejia contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.