As autumn rain in California vanishes amid global warming, fires worsen

Reporting from PARADISE, Calif. — This is a wet place by California standards.

It averages about 55 inches of rain a year, thanks to its prime location in the verdant foothills of the Sierra Nevada, which wrings rain out of Pacific storms.

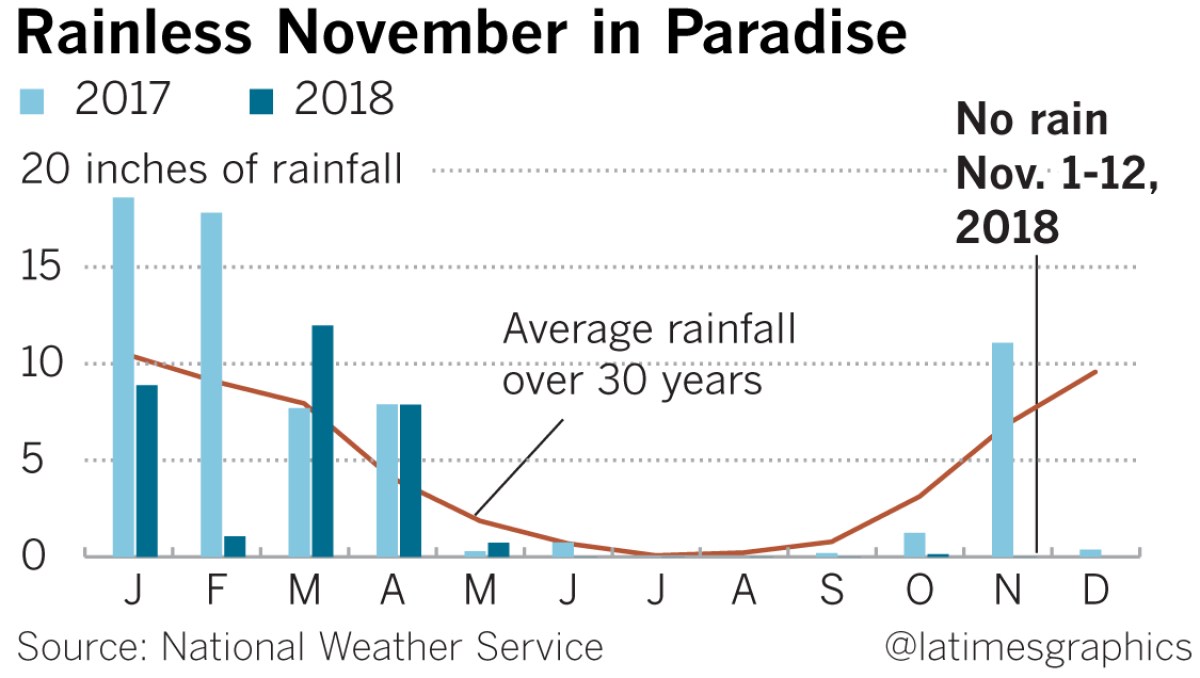

But when the Camp fire sparked last Thursday, Paradise was parched. The area usually gets about 15 storms during the summer and early fall, adding up to five inches of rain. But this year, it got a measly one-seventh of an inch. The vegetation around Paradise was explosively dry, resulting in the worst fire in modern California history that left 7,000 structures destroyed, at least 42 dead and scores still missing.

Across California, the lack of autumn rain is having dire consequences. Ventura County, where the Woolsey fire last week destroyed hundreds of homes, also got almost no rain through the summer and fall. Early storms were supposed to have ended the Northern California fire season by now, allowing more firefighters to head to Southern California to battle fires spread by Santa Ana winds.

With the Camp fire raging in Butte County, officials said there were fewer firefighters at hand to battle the blaze that swept through Thousand Oaks, Westlake Village and Malibu.

“A lot of resources we typically rely on were not available,” Los Angeles County Fire Chief Daryl Osby said. “Our help came from further away,” including as far away as Texas.

Scientists say that in a future affected by climate change, California should expect drier autumns and springs, with more of the rain and snow concentrated in the winter months. That is bad news for firefighters, who rely on early rains to ease the threat from extreme winds that plague California beginning in late September and help quickly spread many of California’s worst blazes.

“I would anticipate we will more frequently see this extension of the fire season into the fall and even into the early winter,” said Nina Oakley, regional climatologist with the Western Regional Climate Center. In the past six years, California’s southern coastal region has been drier than average during the fall.

Climate experts have long said the fire season is really a race over what comes first: the powerful winds or the rain. With much less rain in the fall, “you’re waiting for a disaster to occur,” said John Abatzoglou, a University of Idaho associate professor of geography, who has studied California extensively.

The lack of rain brought record dryness for vegetation, and that has helped fires burn more explosively. Tinder-dry vegetation only fuels fires further; it sent an exceptional amount of heat into the air during the massive Carr fire in July, leading to a “fire tornado” that carved its own unpredictable path in Redding to spread the flames, leading to a death of a firefighter.

In Paradise, about 80 miles north of Sacramento, the dry vegetation contributed to a turbocharged spread that many residents could not outrun.

“It has jumped a 300-foot lake at least three times, [spreading to] areas where you’d expect the fire not to continue forward,” said Jonathan Pangburn, a fire behavior analyst with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

Paradise sits in the foothills of the Sierra, at an elevation of about 1,000 feet. It’s not unusual for the town to get 20 inches of rain in a single month during the rainy season.

“Paradise is a pretty wet place,” National Weather Service meteorologist Johnnie Powell said. “Throughout Northern California, it’s been one of the driest falls.”

Paradise has its rain gauge at a fire station, and that station was one of Powell’s best weather observers. Paradise’s last weather report was sent in on Wednesday, the day before the fire began. Since then, the reporting station has gone silent.

An extremely late start to Southern California’s rainy season last year also contributed to bone-dry conditions just before the Thomas fire in December devastated Ventura and Santa Barbara counties, leading to the second-largest California wildfire in the modern record, burning up 282,000 acres. Typically, more than 4 inches of rain falls in Camarillo between July and December; in 2017, only 0.09 inches fell.

“If Northern California had received anywhere near the typical amount of autumn precipitation this year,” UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain said, “explosive fire behavior and stunning tragedy in Paradise would almost certainly not have occurred.”

If the land around Paradise had been damp, even the strong winds coming downhill — pushed by 50-mph gusts from the northeast — won’t drive the same kind of wildfire, Swain said. “That shortening of the rain season, as we’re seeing two years in a row, is really consequential.”

It’s not just the widening overlap between the dry season and the start of Santa Ana season that’s a problem. Besides the unusually dry weather, increasingly hot temperatures are also drying out vegetation to record levels.

A key thing “you need for these apocalyptic fires is an extremely dry, heavy fuel load,” climatologist Bill Patzert said. “Up and down the state, everyone is in the same situation.

“These more intensive heat waves precondition the brush for more intense fires,” Patzert said.

And it’s been hot throughout the state recently. California experienced its hottest month on record this past July, in terms of highest minimum temperatures recorded statewide. On July 6, all-time temperature records were set across Southern California, with UCLA hitting 111, Van Nuys 117 and Chino 120.

Having late wildfires also poses problems for the rainy season to come. After the Thomas fire hit, weeks later, rains triggered deadly mudslides that killed more than 20 people.

“When you have these wildfires backed up against the first rainfall … there’s very little time to get in teams to do assessments and employ mitigation strategies before rainfall occurs,” Oakley said. “You have communities that are still reeling from wildfire and need to prepare for the threat of post-fire debris flows.”

Lin reported from Los Angeles, Hamilton from Malibu and Serna from Paradise, Calif.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.