Pedestrian deaths surge in L.A., overall traffic fatalities down slightly

Pedestrian deaths in Los Angeles have surged more than 80% in the first two years of a high-profile initiative launched by Mayor Eric Garcetti to eliminate traffic fatalities, new data show.

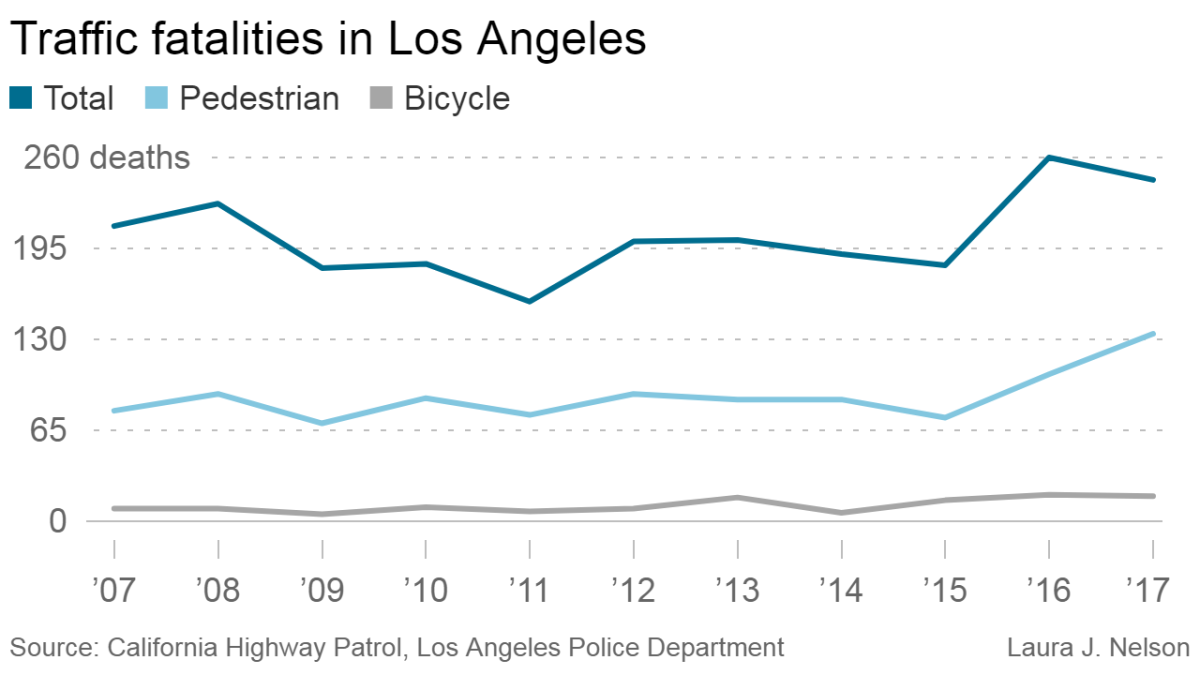

In 2015, 74 people on foot were killed by drivers in Los Angeles. That figure rose to 134 in 2017, the highest number in more than 15 years.

Overall, the number of bicyclists, pedestrians, motorcyclists and drivers killed in collisions on city streets fell last year by 6%, to 244, according to preliminary police data released by the city Transportation Department.

In 2015, Garcetti signed an executive order creating the Vision Zero initiative, which set the ambitious goal of eliminating traffic deaths on city streets by 2025. It called for reductions of 20% by 2017 and 50% by 2020.

The 6% decline in 2017 falls well short of that goal, and the city’s slow progress suggests reducing fatalities by half in the next three years will be difficult.

“Every life is important and we must keep pushing to do better,” Garcetti said Tuesday in a statement to The Times, saying he was proud the city had reduced deaths overall in 2017. “Safety is our top priority, and we will continue to set bold goals.”

The 2017 statistics were included in a report scheduled to be discussed Wednesday at a City Council transportation committee hearing.

The L.A. data are on par with national trends, which show that more pedestrians are dying, and drivers are more distracted, Transportation Department spokesman Oliver Hou said in an email.

Figures on traffic deaths across the country are not yet available for 2017, but in the previous year, pedestrian deaths rose 9% nationally and 42% in Los Angeles.

Los Angeles officials spent more than a year studying collision data to pinpoint the city’s most dangerous streets for pedestrians and cyclists, and worked in 2017 to make changes along 40 of those corridors. Many are broad thoroughfares, including North Broadway in Chinatown, 3rd Street in Koreatown and Sepulveda Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley.

Officials have focused on those areas because pedestrians and cyclists represent an outsize number of the city’s traffic fatalities. From 2012 to 2016, people on foot were involved in 8% of the traffic collisions in L.A. but represented 44% of the deaths, the Transportation Department said.

Last year, the city made 1,120 changes to streets and intersections, Hou said. Hundreds of crosswalks were modified, including four that now allow pedestrians to cross all directions at once, and 144 digital signs were installed that tell drivers their speeds.

Speed is often the determining factor in whether someone survives a car crash. When struck by a car moving at 20 mph, a pedestrian has a 90% chance of survival, but when hit by a vehicle going 40 mph, the chance of survival falls to 20%, according to a federal study of crash data.

The city also changed the timing on 67 traffic lights to give pedestrians the walk signal several seconds before drivers receive a green light. That change — known as a “leading pedestrian interval” — is designed to cut down on drivers hitting pedestrians in crosswalks.

The increase in pedestrian deaths isn’t surprising for anyone who walks in Los Angeles and has had a near miss with a speeding driver, said Emilia Crotty, executive director of Los Angeles Walks, a pedestrian advocacy organization.

Projects that have been shown to reduce pedestrian injuries, including so-called “scramble crosswalks” that allow people to cross in all directions, should not be delayed by concerns about commute times from local officials, Crotty said.

The most high-profile street safety project in 2017, along a handful of streets on L.A.’s Westside, sparked a wave of protests from residents and commuters, two lawsuits and an effort to recall Councilman Mike Bonin, who represents the area. Eventually, the city reversed most of the improvements.

The advocates who fought the Playa del Rey project said they were interested in helping other local groups fight street changes that would affect commute times in other parts of the city. Street safety advocates worried that the backlash could set the Vision Zero effort back by several years.

The city “learned some very hard lessons” last year, Crotty said. “We need our City Council members to champion this issue like the life-and-death situation that it is. Whatever negative pushback there is — perhaps from some drivers — this is what we need to protect the most vulnerable people in our neighborhoods.”

Twitter: @laura_nelson

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.