Ex-deputy: L.A. County sheriff’s deputies beat jail visitor, then lied

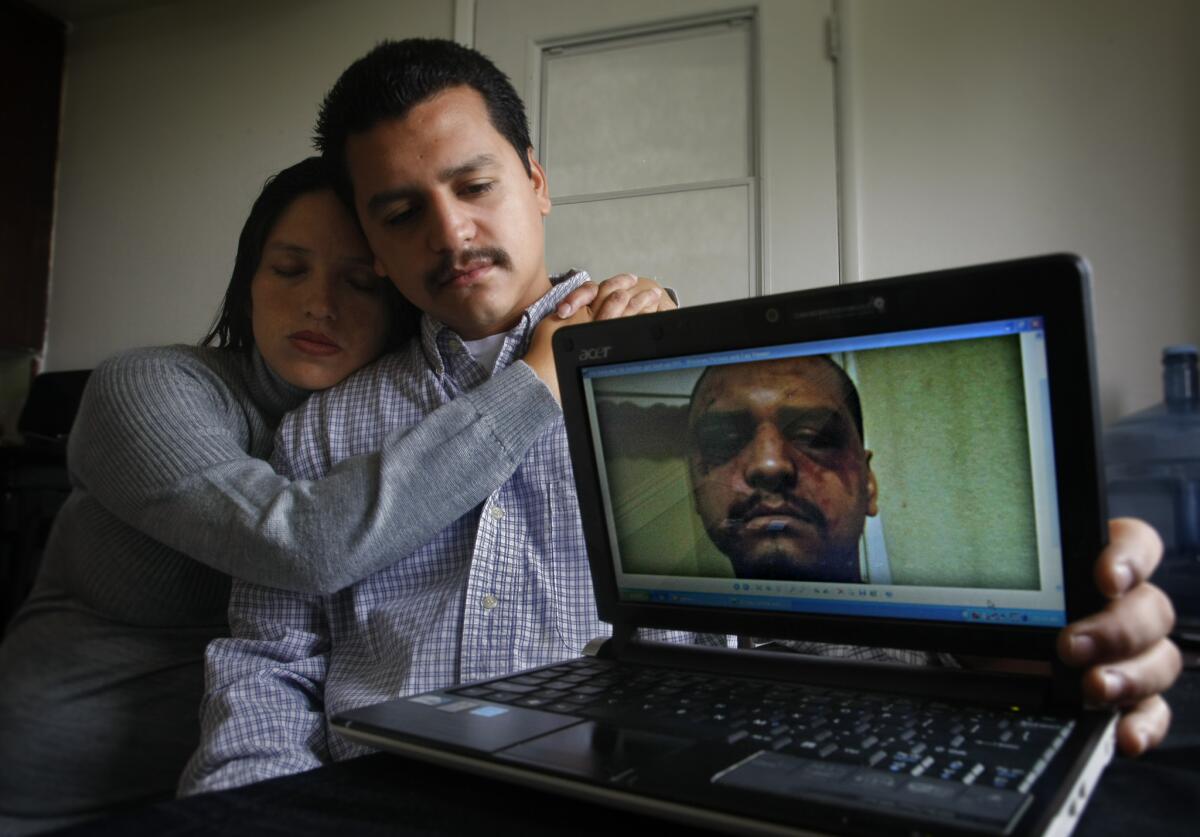

Gabriel Carrillo and Grace Martinez show a photo she took of Carrillo a few days after he was beaten by Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies at the Men’s Central Jail.

Pantamitr Zunggeemoge said he stuck to the script.

After he and other Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies beat a handcuffed man in a jail visitors’ center, he said, they huddled with their sergeant, who came up with a plan. Each of them would claim the man had attacked when one of his hands was uncuffed for fingerprinting.

On Wednesday, Zunggeemoge told a downtown federal jury that he and the other deputies had used excessive force on the jail visitor and then fabricated reports and testimony to justify the beating.

From the outset, it was understood among the deputies that they would keep to the same story, he told jurors.

“We were all partners,” the former deputy said in the criminal trial of three of his former Sheriff’s Department colleagues. “There’s a bond. And you don’t go against your partners.”

Zunggeemoge’s testimony marked the first public accounting by a deputy of the use of excessive force since federal officials opened a wide-ranging investigation into abuse and corruption inside the county’s jail system more than four years ago. He testified for six hours Wednesday, enduring an onslaught of questions from defense attorneys who tried to raise doubts about his credibility and poke holes in his detailed account.

The case centers on the February 2011 beating of Gabriel Carrillo, who had come to the Men’s Central Jail with his girlfriend, Grace Torres, to visit his brother, an inmate.

Both sides agree about the events that led up to the violent encounter: After Torres and Carrillo were discovered in the visitors’ waiting area carrying cellphones in violation of jail rules, deputies handcuffed them and brought them into a separate room. An angry Carrillo mouthed off repeatedly to the deputies.

Deputies Sussie Ayala and Fernando Luviano and former Sgt. Eric Gonzalez, a supervisor at the jail visitors’ center, face charges of excessive force and falsifying records. They have pleaded not guilty, insisting that Carrillo was uncuffed, fought with deputies and that the force used on him was necessary to subdue him. Ayala and Gonzalez are also accused of conspiring to violate Carrillo’s civil rights.

In the months leading up to trial, prosecutors managed to turn Zunggeemoge and another deputy, Noel Womack, who also faced charges in the Carrillo case.

Zunggeemoge acknowledged in court that as part of his deal with prosecutors, he pleaded guilty to misdemeanor counts of conspiracy and deprivation of Carrillo’s rights and has been banned from working in law enforcement. He could be sentenced to up to two years in prison.

Womack, who earlier this month pleaded guilty to a felony of lying to federal investigators, is expected to testify later this week.

Under questioning from Assistant U.S. Atty. Lizabeth Rhodes, Zunggeemoge described the encounter with Carrillo, saying repeatedly that the man had been handcuffed throughout.

Zunggeemoge recalled confronting Carrillo in the jail’s visiting center over carrying a cellphone. He said he cuffed both of Carrillo’s hands behind his back and brought him to a side room that deputies use as a break room. Zunggeemoge shoved the visitor up against a refrigerator and started patting him down, he testified.

Annoyed that Carrillo questioned him about why he had been detained, Zunggeemoge said he lifted the visitor’s handcuffed hands upward behind his back during the pat down “so he could feel some pain.”

After retrieving the cellphone, Zunggeemoge said, he left the room to run Carrillo’s name through a criminal database and when he returned, he found Luviano trying to restrain Carrillo as Ayala and Gonzalez watched.

Zunggeemoge testified that he was uncertain of what was happening and rushed to help Luviano. Together, the deputies took Carrillo to the ground, his face slamming into the floor, Zunggeemoge said. Once on the ground, Zunggeemoge said, he realized Carrillo was still handcuffed. The beating continued nonetheless, he said, as Luviano repeatedly struck Carrillo’s face and Zunggeemoge punched Carrillo’s legs, lower back and ribs.

Rhodes asked whether there was “any legitimate law enforcement purpose” for the blows. Zunggeemoge replied that there was not.

“And did the force exceed what was necessary at the time?” Rhodes asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” the former deputy said.

Luviano used pepper spray on Carrillo’s face, prompting him to become teary and start moaning, Zunggeemoge testified. Mucus ran down Carrillo’s nose and face and he had trouble breathing, Zunggeemoge said. When Carrillo turned his face in Zunggeemoge’s direction to shield it from the spray, Zunggeemoge punched Carrillo twice in the face.

After the incident, Zunggeemoge, Gonzalez, Luviano and Ayala gathered to discuss the account they would concoct to justify the force, Zunggeemoge said. Gonzalez, he said, was the driving force behind the strategy and stood next to him as Zunggeemoge wrote his report at a computer terminal.

“He was basically telling me what to write,” Zunggeemoge said.

Gonzalez, sitting at the defense table, shook his head as he listened to the testimony.

Along with the report, Zunggeemoge said, he lied during a preliminary hearing after Carrillo was charged with assault.

“I didn’t want to be the one who told the truth about what really happened,” Zunggeemoge said when asked why he had lied. “Everyone was going to go with the story we made up.”

He said he also lied during the sheriff’s internal investigation because he knew he could lose his job and face prosecution if he told the truth.

Attorneys for the three defendants took turns questioning Zunggeemoge, trying to expose inconsistencies between his testimony and earlier statements he made to prosecutors.

Zunggeemoge generally appeared to be untroubled until Patrick Smith, Ayala’s attorney, flummoxed him somewhat when he got Zunggeemoge to admit that he believed he was justified in punching Carrillo in the face because he feared the man would spit blood and saliva onto him if he hadn’t. Smith pressed on, asking Zunggeemoge if he was “just telling the prosecution what they want to hear?”

Ayala and Luviano have been relieved of duty pending the outcome of the trial. Gonzalez left the department in 2013.

For more news on the federal courts in Southern California, follow @joelrubin.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.