With signs, Northern California county declares it has ‘no room for racism.’ Reality is more complicated

The signs stand throughout rural Shasta County.

There’s the one on Lake Boulevard, a quiet two-lane that cuts through the trees south of the towering Shasta Dam. One stands on Olinda Road in Anderson, just west of North Valley High School. Another hangs from an electric pole in Redding, across the street from Kent’s Meats & Groceries.

“No Room for Racism,” they declare unequivocally and without margin for debate.

But, of course, in all matters of race — and all that comes with it — it’s never as easy as putting up a sign.

With its small towns and stunning mountain vistas, Shasta County is mostly white and a growing anomaly in this diverse, liberal state. In this Northern California county, 80% of residents are white, compared with just 38% in California as a whole.

President Trump won Shasta County with 65% of the vote. In early February, the county voted to become a “non-sanctuary” zone for immigrants in the country illegally.

Just after Trump won the presidency, a student at Redding’s Shasta High School handed out fake deportation notices to students of different ethnicities. Earlier that year, students at nearby University Preparatory School attending a basketball game against a largely Latino Colusa County team held up signs with pictures of beans and shouted that opposing players were “felons.”

“There’s no diversity. How can you educate kids how to go out into the world when the diversity doesn’t exist?” said Trent Copland, a member of the U-Prep school board and a retired English-as-a-second-language teacher.

It was here, at a campaign rally at the Redding Municipal Airport, that Trump pointed to Gregory Cheadle, a black man in the mostly white audience, and said: “Look at my African American over here! Aren’t you the greatest?”

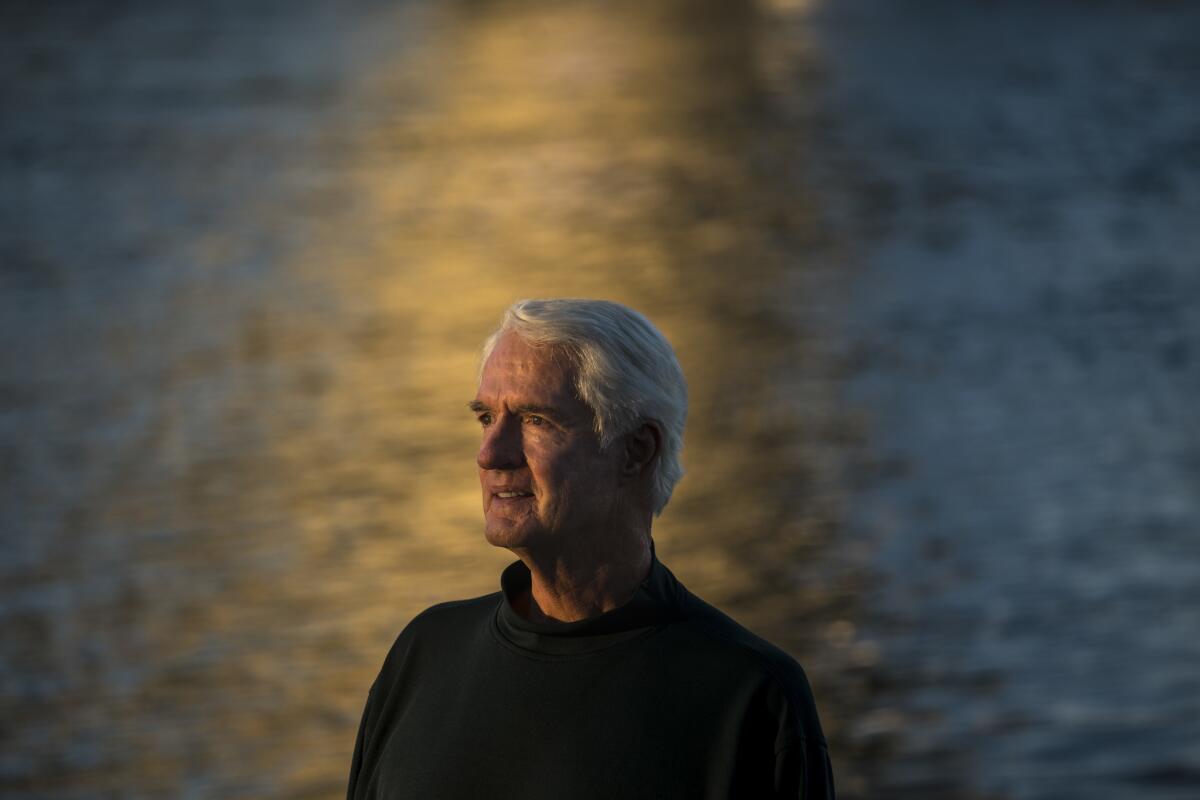

Cheadle, a longtime resident who said “some of the nicest people that you could ever meet” live here, chuckled when asked recently about the No Room for Racism signs. It’s easy to say racism doesn’t exist when you live in a place where the non-white population is so small, he said.

Cheadle, who is running for Congress, said people often tell him they’re not prejudiced, or mention that they have a black friend.

“I think people have good hearts,” Cheadle said. “But you need more than a good heart to put an end to racism. … I appreciate the gesture, but we have to do much more than put up a sign.”

It was a series of tragic events that brought the signs to Shasta County — and, this being a rural place with fewer people and less bustle, dark events tend to linger more intimately in people’s memories.

In the summer of 1988, a black man and a white woman standing together in Redding’s Caldwell Park were shot at by someone in a passing car who shouted racial epithets. No one was physically hurt, but a group of residents were so appalled by the shooting and other racially motivated incidents that they formed a group called Shasta County Citizens Against Racism.

The region, at the time, also was experiencing an influx of Southeast Asian refugees, and one man walked through a predominantly Asian neighborhood in Redding, smashing car and house windows and yelling “Learn English!” and “You’re not welcome here!”

By 1994, SCCAR wanted elected officials and schools to take a stand. They proposed the No Room for Racism signs.

"Our argument was that this is affecting our community. Why don’t we publicly stand up and affirm what our values are?” said Tom O’Mara, a longtime member of SCCAR (which has been renamed Shasta County Citizens Advocating Respect) and a civil rights advocate for the Redding Police Department.

The Redding City Council quickly approved the signs, and the first was posted on Abraham Lincoln’s birthday in February 1995.

The Shasta County Board of Supervisors and the city councils in Shasta Lake and Anderson initially said no to the signs. One reason they gave, O’Mara said, was that the signs would distract motorists. Those governing boards later changed their minds.

In Anderson, that took a decade.

In 2004, a white supremacist in that town burned an 8-foot cross in the yard of a black family in his neighborhood. It so stunned the community that hundreds of people marched in the pouring rain to denounce racism. The municipal signs — which say “No Room for Racism, Hate or Violence” — went up in Anderson shortly afterward.

“I’ve received emails that say, ‘How bad is it that you actually have to put up signs,’” O’Mara said. “I think most of our issues here are due to a lack of exposure. … There are just so many people here who have met very few black people or very few Filipino people or very few gay people. It’s a very white, very Christian community.”

Redding Police Chief Roger Moore said racially motivated incidents stay in people’s consciousness for a long time and that his department tries to discuss and deal with them openly. They distribute pamphlets describing what a hate crime is, and Moore personally reviews each potentially hate-related incident, often with O’Mara. School resource officers are trained to intervene when they learn of a student who might be veering into white supremacist ideology.

“We have realized that if we don’t do something, the wake of disaster [that] could create in a community, and the distrust,” he said. “You can’t get that back for years and years and years, and so to maintain that community trust is essential.”

On Feb. 6, the all-white Shasta County Board of Supervisors — as the boards in nearby Siskiyou and Tehama counties did earlier — approved a resolution declaring the county a “non-sanctuary” zone in defiance of California’s laws seeking to protect undocumented immigrants from deportation. The city of Anderson passed a similar ordinance last year.

The resolution sparked a bitter debate in Shasta County, with detractors calling it racially motivated and unnecessary and supporters calling it a public safety measure.

“If you say something against an illegal, you automatically become a bigot, or you automatically become a racist,” said Supervisor Steve Morgan, who voted for the resolution.

Shasta County doesn’t “have that big of an influx that we know about as far as illegal aliens,” Morgan said. But he wanted to send a message to Sacramento that federal immigration law has precedence over state law.

Supervisor Mary Rickert, who also voted for the measure, said during the board meeting that she doesn’t “look at this as a racial issue whatsoever.” She noted that she and her husband have employed “several Hispanic families” and helped some undocumented people get citizenship.

“I have French heritage,” she said. “My gosh ... the French, they get a lot of bad press. And I’m also Irish and I’m also Scotch. We’re all immigrants, but every single one of my ancestors became citizens of this wonderful country.”

The resolution, Supervisor Leonard Moty, a former Redding police chief, said in an interview, was “nothing more than election year politics” and just an effort to blame a group of people for all the county’s ills. Moty abstained from voting on it.

“Let’s be honest. The immigrant population in Shasta County is not big,” he said. “The immigrant population does not create our crime problem. … What do we have here? A bunch of white people who are committing the crimes, who are doing the drugs. ... It’s not some other population that showed up from some other country.”

Justin, a soft-spoken, 15-year-old undocumented high school student, heard about the non-sanctuary resolution on the news and told his parents it scared him. (He asked that his last name not be used because his family fears deportation.)

“I said, it’s not a sanctuary anymore,” Justin said. “We should leave. … I feel like I have a big red thing on my head, like a target. I’m not really comfortable being here.”

His family fled Mexico City when he was a baby after his mother’s sister was murdered.

Justin, who hopes to be a nurse someday, said kids at school asked him what he thought about Trump right after the election. He lied and said he was a “good guy” so they wouldn’t harass him. He’s been taunted before, called a “beaner” and a “wetback.”

“That really hurts me, you know?” he said, his voice quiet. “I’m really proud of being Mexican. … I love the culture and everything. It’s kind of messed up.”

At the Sikh Centre in Anderson, worshipers remove their shoes before walking into the prayer room. The smell of Indian food wafts through the temple.

In March 2007, just before the temple opened, a man stole a front-end loader tractor from a nearby heavy-equipment yard and repeatedly smashed it into the gurdwara. Authorities said the man thought the building was owned by Arab foreigners who didn’t believe in Jesus and that he was angry at them for building the temple.

Amarjit Singh Grewal, the temple’s priest, had moved to Shasta County from India just before the incident. But he has always felt accepted here, and he actively invites non-Sikhs to visit the temple, he said.

The temple even recently hosted an immigrants’ advocate after the passage of the non-sanctuary resolution to teach people their rights if they are detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents because there is “fear in the community,” Grewal said.

“My nature is to love humanity,” he said. “So, to do that, I love to work in the community, talk to people from different faiths and cultures. I understand there are a lot of differences … but when you come to a common platform, you love each other.”

Displayed in the temple’s sunlit entryway is a green sign: “No Room for Racism.”

To read the article in Spanish, click here

Twitter: @haileybranson

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.