‘It feels like we go from one tragedy to another’: After slayings at North Park Elementary, San Bernardino grieves again

Lili Flores, a staff analyst for San Bernardino County, was at work not far from the Inland Regional Center when a husband and wife opened fire on an office holiday party there in 2015, killing 14 people, most of them her co-workers.

She was at work again Monday when she learned of the shooting at North Park Elementary School, where her son Christian is in fourth grade. She waited in anguish, through the “worst hours of my life,” she said, before learning in a message from his teacher that her child was safe.

“It feels like we go from one tragedy to another,” Flores said. “Not only that but the gang violence, the killings of people, the robberies, the increased rate in crime.”

The slaying of teacher Karen Smith and 8-year-old Jonathan Martinez, and the wounding of a 9-year-old, in a classroom for special needs students at North Park was a tragedy of domestic violence — one that might have happened in any city or town. But it happened in San Bernardino, which has endured multiple waves of heartbreak, especially in recent years.

Confronted by the horror of Monday’s shooting, residents face a grief compounded by experience — with the Dec. 2, 2015, terror attack, with the city’s surge in homicides, with its poverty, its routine violence and crime.

“It’s a lot, and I think people feel a little overwhelmed,” said Pastor Joshua Beckley of Ecclesia Christian Fellowship, who has worked with other pastors on efforts to curb the city’s violence. “We were just kind of settling in to a sense of peace and comfort that some of the activities we were doing to curb crime were starting to take effect, and then this tragedy happens … and it puts the city in an upheaval all over again.”

In a way, though, those experiences have made city leaders primed to respond to that grief in a way few cities might.

“For us as pastors and civic leaders and law enforcement, it becomes about how do we get our people back down, get them comfortable and let them recognize that even though this is a major tragedy, this will not escalate into something we can’t control,” Beckley said.

On Monday evening, as more than 300 residents gathered at Our Lady of the Assumption Church for a vigil to mourn the dead, the city’s history of violence and tragedy was never far from the surface.

One man wore a shirt that read “No more violence in SB.” Others read “SB Strong” — a slogan of resilience that residents adopted after the 2015 attack. A group passed out fliers for a monthly prayer walk to remember those who have been killed in the city.

“We gather to pray … that this community, that has experienced so many things, that we start healing,” Father Henry M. Sseriiso told the mourners.

John Andrews, a spokesman for the diocese, said officials organized the vigil knowing from experience that the community would benefit from having a place to assemble and mourn on the same night as the incident. After the Dec. 2 mass shootings, the first formal vigils were held the following day, he recalled.

“We learned that people are grieving right away and the sooner you can provide them a forum to gather and pray and to grieve together, the better it is to be able to do that,” he said.

As in the aftermath of the terror attack, residents again pledged resilience.

“We’re proud, despite what happens, because of things like this,” said Ericka Gomez, 24, as she looked at the parents, teachers, children and others who gathered outside the church, holding candles and offering prayers for the dead, for their families and for the city.

But for others, like Flores, there is a sense that the city’s burdens have become simply too heavy.

“It’s getting to the point where it feels so unsafe, and so sad,” she said.

A makeshift memorial sprang up outside North Park Elementary School in San Bernardino, where a gunman opened fire on his estranged wife, a teacher at the school, and then killed himself. Stray bullets struck two students, killing one.

While San Bernardino has long struggled with high levels of violence, last year it marked a grim milestone as police recorded 62 killings — making it the deadliest year since 1995.

The numbers have fallen so far this year, but only slightly. There have been 15 homicides, compared with 17 at this time last year, said police spokesman Lt. Mike Madden.

Yet even as it continues to struggle, the city has made strides toward improvement.

It has all but formally emerged from a more than four-year bankruptcy. A new city charter meant to make local government more efficient was adopted. And officials are working to boost the Police Department and to implement an innovative program aimed at blunting the city’s violence.

Residents have also created organizations that work together to respond to crises in the city.

A network of pastors received a text message about Monday’s shooting and within half an hour, Beckley said, dozens of them had responded to offer help, first at North Park and later at Cajon High School.

“Two years ago, where a phone tree got everybody together,” he said, “this time it was just a simple text message because we’d already established an infrastructure for emergency response for clergy and community leaders.”

Terrance Stone, chief executive of the Young Visionaries Youth Leadership Academy, a nonprofit that provides outreach and training to the city’s youth, also rushed to Cajon High School, where North Park parents had gone to reunite with their children.

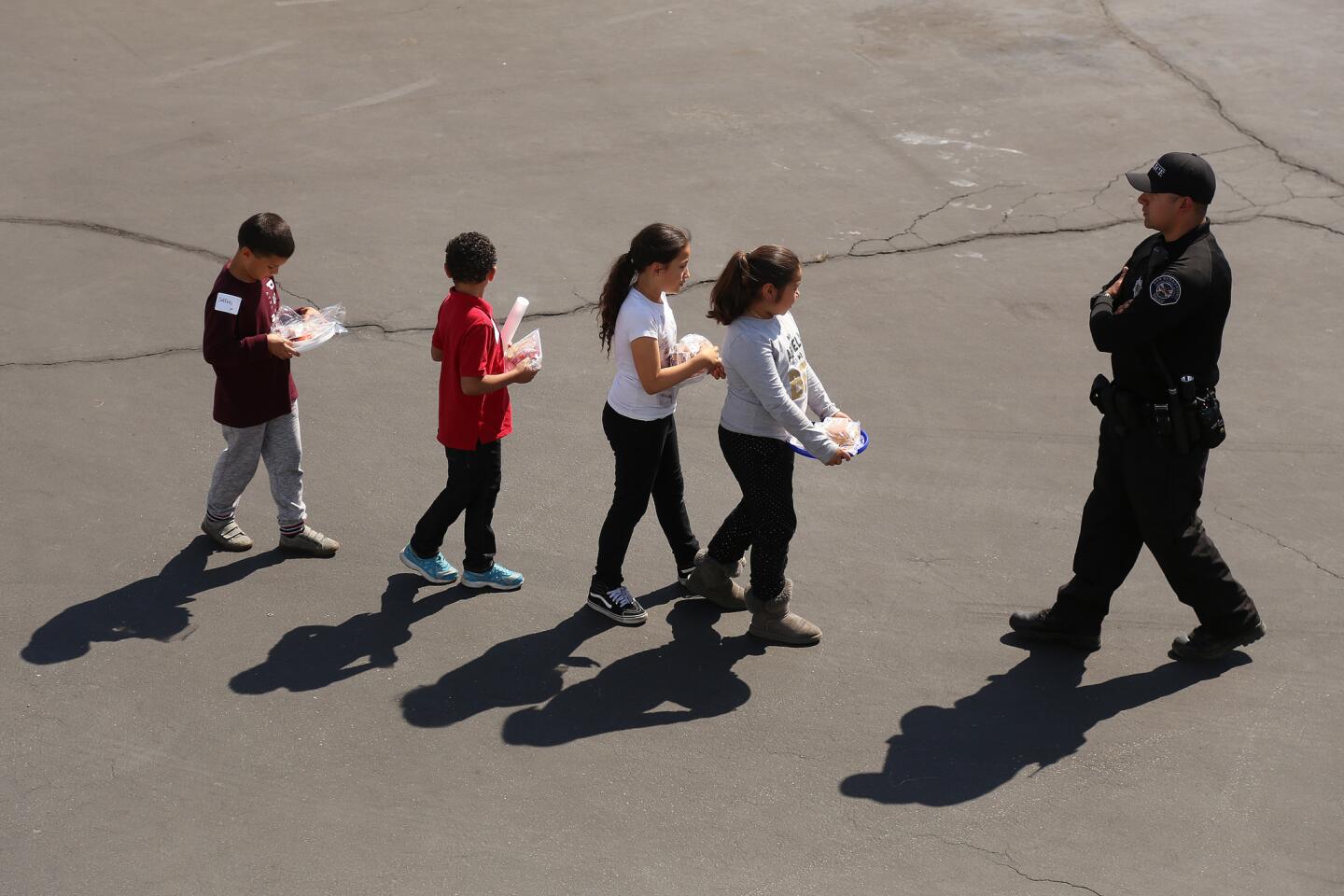

Many of them had anxiously watched TV news images of children gathered on the school playground surrounded by police with long guns, not knowing for sure whether their own children were safe.

Some of the children who would soon arrive at the campus had watched in terror as their teacher and classmates were gunned down.

At Cajon, the volunteers scrambled to provide water, snacks and whatever encouragement they could offer.

A police officer brought Sherlock, the department’s community affairs rescue dog, in hopes of comforting the students.

Providing support was a ritual many of these volunteers had offered on Dec. 2, 2015.

And it’s one that many of them have done since, as they respond to family homes after a homicide.

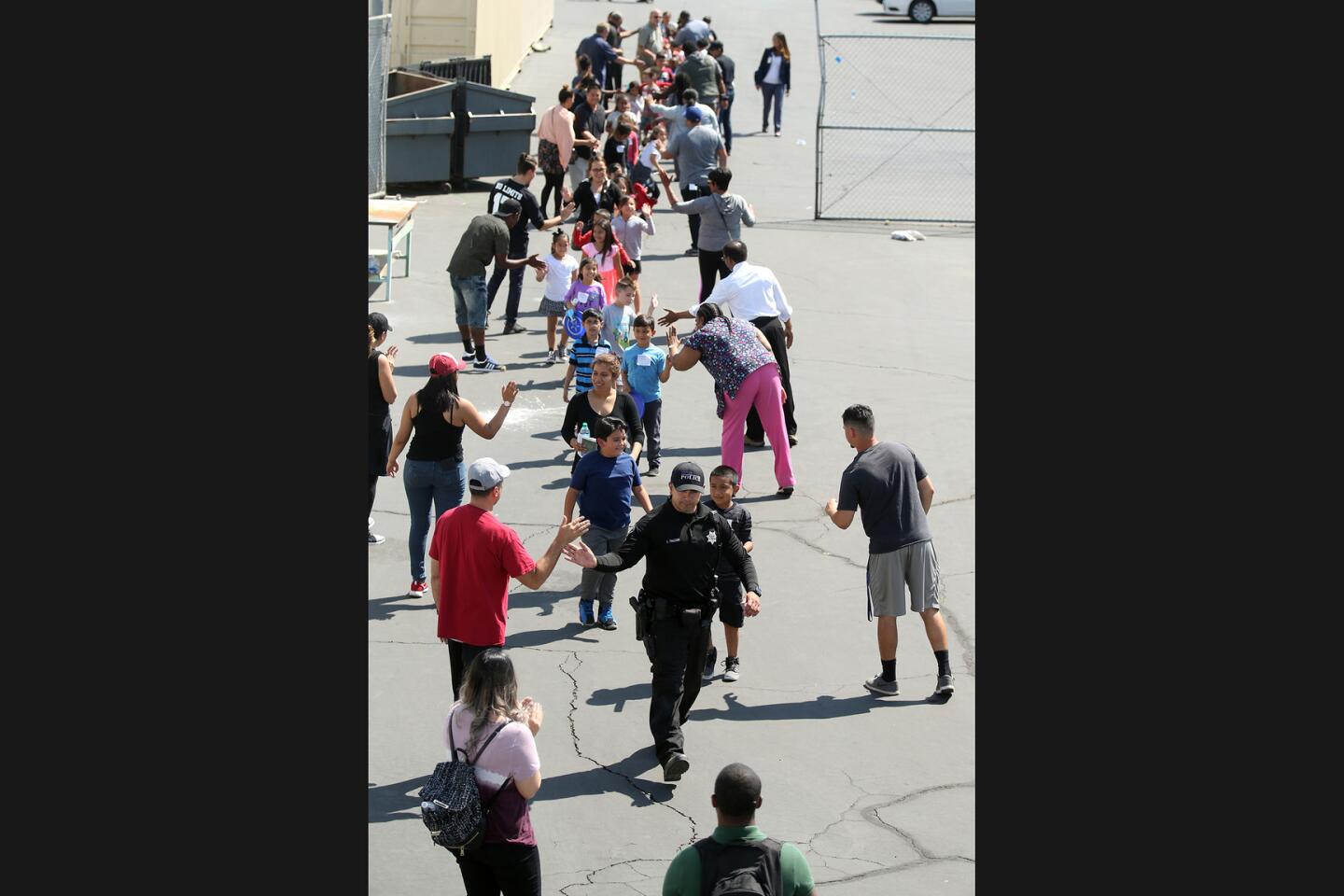

As the students arrived on buses, Stone and the others gathered in parallel lines and formed a cheering squad. Many of the same volunteers had done the same thing at Lincoln Elementary School last year, after the shooting death of 9-year-old Travon Williams. They offered hugs, high-fives and applause.

The idea, Stone said, was to hearten and reassure them that the community was with them.

“We didn’t want to make it any more tragic than it was, or cause any more trauma to those kids,” Stone said.

“Even though our city can’t catch a break,” he said, “one thing I know, and I see, is that this community comes together.”

Twitter: @palomaesquivel

ALSO

Murder-suicide in San Bernardino classroom: ‘He just shot everywhere’

‘She thought she had a wonderful husband, but she found out he was not wonderful at all’

Teacher killed in classroom shooting was devoted to her students, mother says

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.