L.A. may charge drivers by the mile, adding freeway tolls to cut congestion

For years, Southern California lawmakers have tried to steer clear of decisions that make driving more expensive or miserable, afraid of angering one of their largest groups of constituents.

But now, transportation officials say, congestion has grown so bad in Los Angeles County that politicians have no choice but to contemplate charging motorists more to drive — a strategy that has stirred controversy but helped cities in other parts of the world tame their own traffic.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority is pushing to study how what’s commonly referred to as congestion pricing could work in L.A., including converting carpool lanes to toll lanes, taxing drivers based on the number of miles they travel, or charging a fee to enter certain neighborhoods and business districts.

Imposing more tolls would offer a smoother drive for those who choose to pay. Getting more drivers off the road could free up space to speed up bus service, while the billions of dollars in revenue could fund a vast expansion of the transit network, Metro said.

But a shift away from mostly free driving in Southern California, where three in four commuters drive alone to work, would require courageous politicians who are willing to champion the policy, explain it to outraged motorists and stand by it if the implementation gets rocky, experts say.

“It challenges what Angelenos see as their God-given right to drive anywhere they want,” said Manuel Pastor, director of USC’s Program for Environmental and Regional Equity. “It would be a challenging shift in a city that’s very much a car culture and an individual culture.”

Next month, Metro’s board of directors will be asked to approve a study and assemble a panel of experts to examine how congestion pricing would work. The process would take about two years, Metro said.

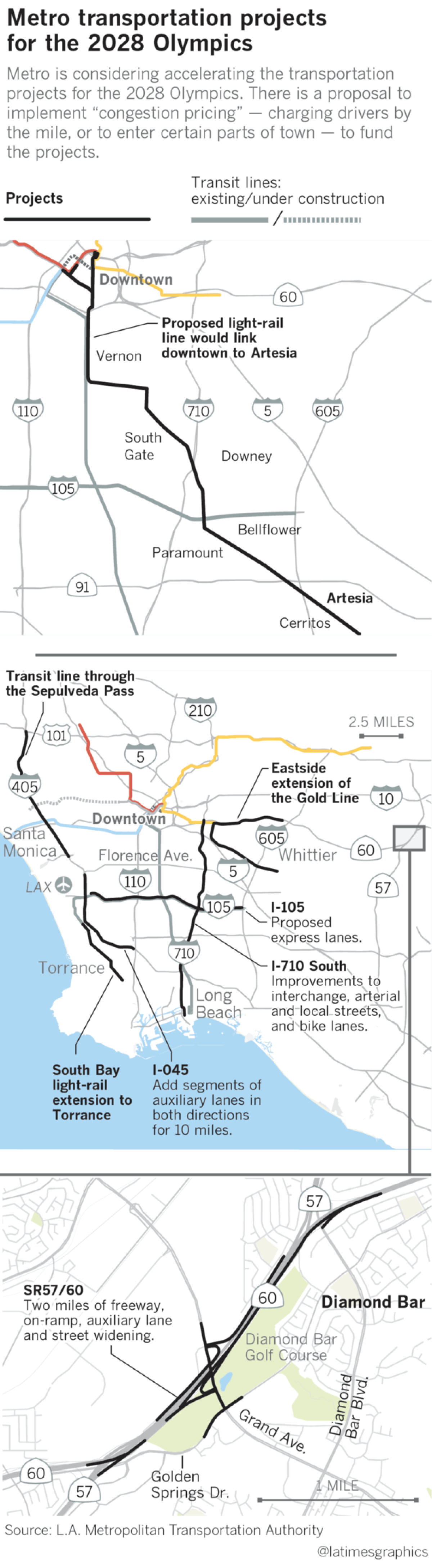

It’s one of many strategies transportation officials are considering to pay for the construction of 28 transit and highway projects before the 2028 Summer Olympic Games, a list dubbed “28 by ’28.”

Twenty of the projects are slated to be finished within the decade, including the Wilshire subway extension to West Los Angeles, and light-rail lines through South L.A. and Van Nuys. Metro would need an additional $26.2 billion to build the other eight projects by then. Those include several interchange improvements, a rail line to Artesia and a Sepulveda Pass transit line.

Using congestion pricing would by far be the most lucrative strategy. According to agency estimates, a per-mile tax on driving could raise $102 billion over a decade, while a fee to enter downtown could raise $12 billion.

“This is the eradication of congestion,” said Metro Chief Executive Phil Washington, who said the benefits would reach beyond 2028. “This is sending out a message to the world that Los Angeles County is doing something about its traffic.”

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti said the Olympics transit and highway projects should be “disentangled” from the question of congestion pricing.

He said Metro can close the $26.2-billion gap by pursuing federal funds and other financing strategies to build on the money raised through Measure M, the sales-tax increase voters approved in 2016.

“I don’t yet support any particular proposal or congestion pricing as a philosophy,” Garcetti said. “But if it can work and if it can help us achieve our goals... I think it’s a conversation worth starting. I’m going to push very strongly to do that.”

Metro’s directors are scheduled Thursday to approve a list of initiatives that Washington calls “sacred cows” — transportation projects too important to be delayed or stripped of funding, even with the $26.2-billion gap. They include an overhaul of the bus network and ongoing system repairs.

Metro also will endorse 11 strategies for finding the funding, including congestion pricing, federal money tied to the Olympics, and a fee added to Uber, Lyft and scooter trips. Officials have cautioned against raising fares or the agency’s debt capacity.

A modest form of congestion pricing is already in place on the 110 and 10 freeways, where drivers who are alone in their cars can pay by the mile to use carpool lanes. As congestion in the lanes rises so do the tolls, to a maximum of more than $20 for a one-way trip.

Expanding those lanes to other freeways would be a good first step toward a more complete pricing system, said Martin Wachs, a distinguished professor emeritus of urban planning at UCLA. That change would help regulate traffic flow and let some drivers pay to get places faster, he said.

Similar strategies have relieved gridlock in every city where they have been tried, including Singapore, Stockholm and London.

In 2003, officials imposed a toll to enter London’s city center between the hours of 7 a.m. and 6 p.m. Over a decade, the change — fought by auto interest groups and business owners — reduced congestion by 10% and raised the equivalent of $3 billion.

In the United States, the idea has been a non-starter. In New York City, the idea has died and been resurrected so often since the 1970s that the New York Times dubbed it “the Lazarus of congestion plans.”

Two years ago, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo backed the idea of tolls to enter Manhattan as a way to raise money for the city’s crumbling, century-old subway system. Congestion pricing, he said, was “an idea whose time has come.”

That time was not in an election year. The plan died in the state Legislature in 2018 but was reintroduced last week in Cuomo’s State of the State speech.

“This would take a very dynamic leader and a very committed leader, and most American politicians back away when they see the opposition,” Wachs said. “Besides it being controversial, one can also say it’s only been adopted in places where someone has made it a cause celebre.”

It’s unclear whether that place is Los Angeles.

The region has never been known for its quick acceptance of new transportation ideas. In the 1970s, a new carpool lane on the 10 Freeway sparked outrage, and its champion was dubbed “the Madwoman of Caltrans.” The elimination of nine miles of traffic lanes on the Westside in 2017 led to an unsuccessful effort to recall L.A. Councilman Mike Bonin.

“As people start complaining, it’s incredible how elected officials’ opinions can change,” Washington said. “This is going to be political intrigue at its best.”

The idea of paying more to drive is unpopular among commuters. In 2016, more than 71% of voters supported Measure M, but just 38% of those supporters favored freeway tolls, according to a recent UCLA study. Among those who didn’t back the tax increase, support was lower, at 16%.

And though voters have shown they are willing to spend billions to expand transit, they don’t ride it themselves. Last year, ridership on Metro’s buses and trains fell to 383 million trips, a 3.4% decrease from 2017 and a 19.7% drop over five years.

Meanwhile, high rents and home prices have pushed Southland residents farther into the exurbs and onto the freeways at rush hour, said Hasan Ikhrata, who spent 10 years as executive director of the Southern California Assn. of Governments.

“We’re not adding any more freeways, period, in the L.A. area,” said Ikhrata, now the executive director of the San Diego Assn. of Governments. “The only thing left to us is to manage the car and price the system.”

To make the charges palatable to drivers, experts say a congestion pricing scheme must be coupled with frequent, reliable public transportation service, so people don’t feel as though they’re being pushed out of their cars with no other options.

“I know that some people need their cars, and we’re not saying to park your car forever,” Metro’s Washington said. “Instead of driving all the way downtown, maybe you drive to a park-and-ride and get on one of our express buses, or the train.”

The billions of dollars that congestion pricing would generate could pay for an investment in transit so major that buses could run every 90 seconds on many streets, Washington said. Metro could also subsidize fares with the revenue, making public transportation free.

If feasible, those plans would address some concerns that tolling would impose a disproportionate burden on low-income residents, similar to the accusations of “Lexus lanes” that were leveled at the toll lanes on the 110 and 10.

Without resolving those equity concerns, congestion pricing “is not going to pass political muster,” Pastor said. “Those FasTrak charges are a big burden to someone who’s a minimum-wage worker or someone who’s a lower-middle-income worker.”

The key, experts say, will be to assure the public that congestion pricing will be a good investment, guaranteeing that if drivers choose to pay, they will save time on their commutes.

“You need the stars to align, in terms of the public’s readiness and a solid plan,” said Carter Rubin, a mobility and climate advocate with the Natural Resources Defense Council. Skepticism is expected, he said, but he hopes people will learn they “can have Sunday morning traffic seven days a week.”

Times staff writer Dakota Smith contributed to this story.

For more transportation news, follow @laura_nelson on Twitter.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.