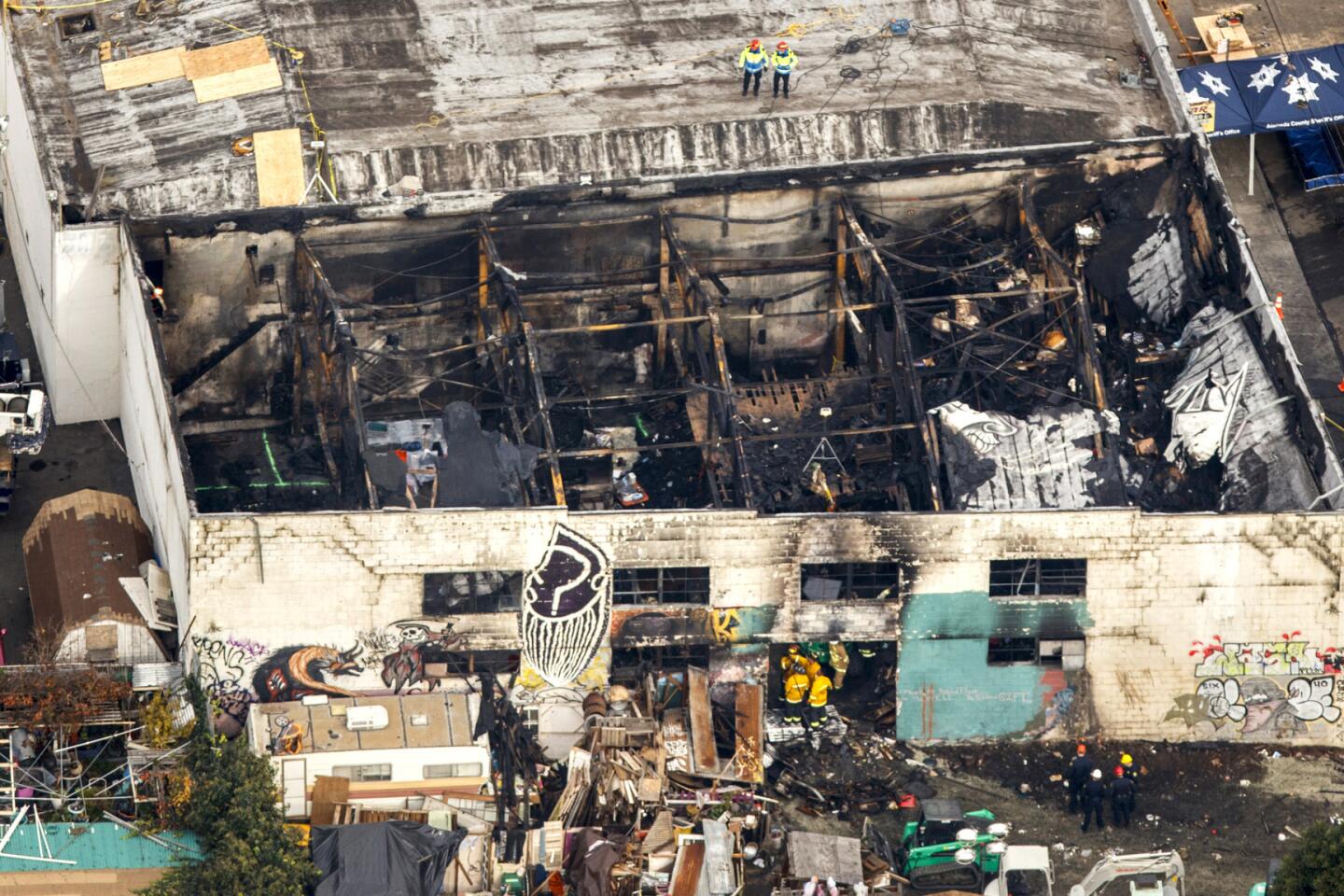

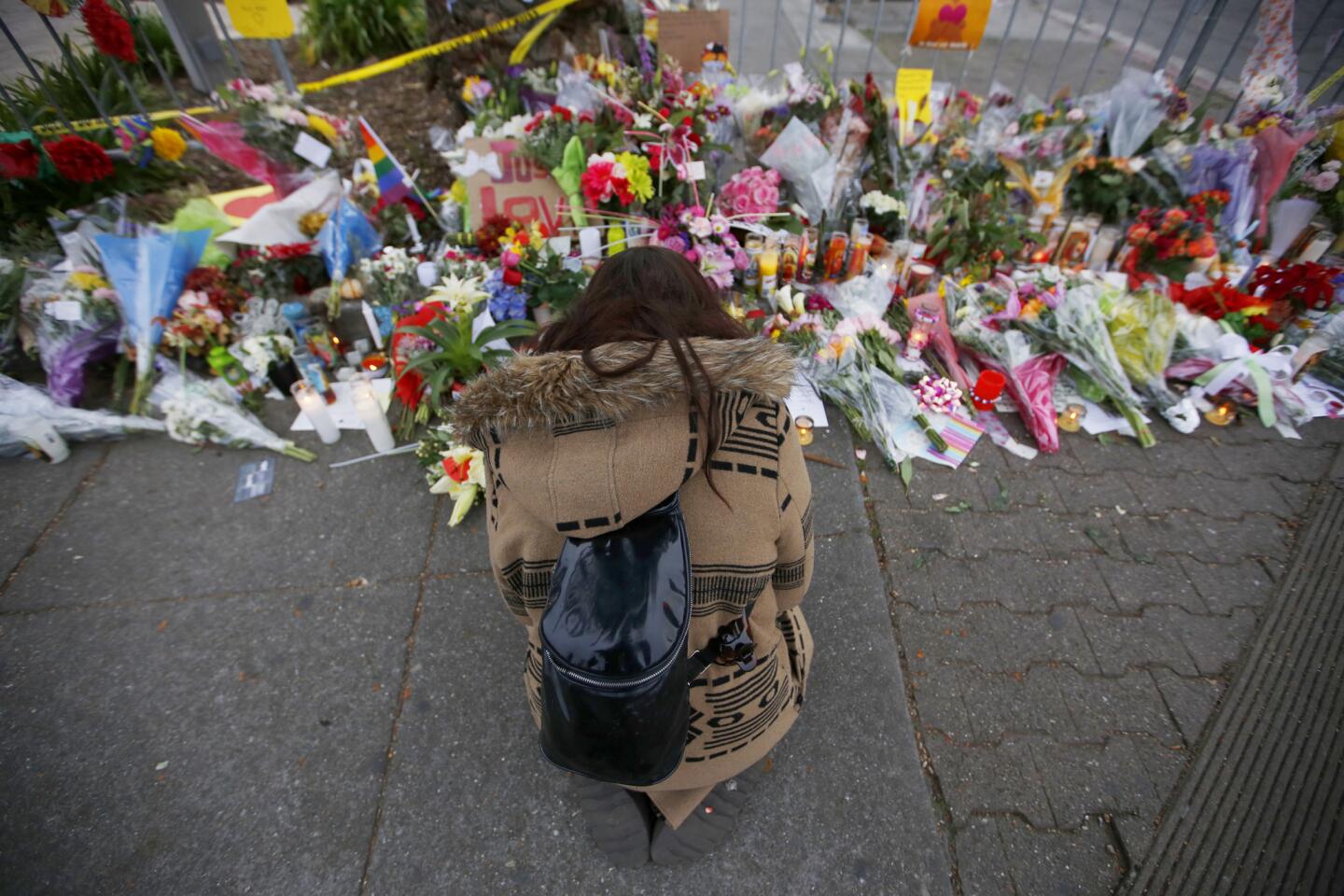

Oakland warehouse manager mournful but defiant after 36 die in fire at artists collective

If the fire is determined to be an arson, prosecutors could bring murder or aggravated arson charges — with one count for each person killed.

The manager of an Oakland warehouse said he was “incredibly sorry” for a devastating fire that killed at least 36 people during an electronic music event Friday night, but balked when asked if he should be held accountable for the loss.

In an interview with the NBC “Today” show on Tuesday, Derick Almena, who manages the building, said he was just trying to create a venue that would host at-risk youth, the gay community and underground artists. Almena said he signed a lease “and I got a building that was to city standards, supposedly.”

When asked if he should be held accountable for the fire, Almena became visibly upset.

Standing outside the fire-gutted building, he said, “What am I going to say to that? Should I be held accountable? I can barely stand here right now.”

Almena declined to talk about reports from former residents who described the building as a “tinderbox” and “death trap” filled with RVs and pianos.

“I don’t want to talk about me,” he told host Matt Lauer. “I don’t want to talk about me. This is not profit. This is loss. This is a mass grave.”

“I am only here to say one thing is that I am incredibly sorry and that everything I did was to make this a stronger and more beautiful community and to bring people together,” Almena said. “People didn’t walk through those doors because it was a horrible place.”

He called himself “the father of this space.”

Almena said he wasn’t at the warehouse on Friday night because he wanted to get a “good night sleep” with his children and wanted to “let the young people do what they needed to do.”

“I didn’t do anything ever in my life that would lead me up to this moment,” he said.

Almena declined to answer questions about the safety conditions inside the warehouse, saying he “would rather get on the floor and be trampled by the parents.”

“I’d rather let them tear at my flesh than answer these ridiculous questions,” he told Lauer.

The warehouse, he said, turned into something more than an artists collective.

“Eventually you can’t pay your rent because your dream is bigger than your pocketbook,” he told Lauer. “When the need for housing, when the need for people to be able to sit down and be warm and make food and take a shower and take a bath and go to bed, so we created something together.”

The building was leased to the Satya Yuga Collective, operated by Almena. According to those who lived there, Almena collected the rent and lived in the warehouse with his wife, Micah Allison, and their three young children.

Almena and Allison’s management of the warehouse was filled with drama and legal sparring with tenants and partygoers.

After an erotic-themed New Year’s Eve party in 2014 — the warehouse’s “twisted stairways,” “hidden coves” and secret nooks strewn with pillows and blankets were billed as attractions — a San Francisco event producer, Philippe Lewis, returned to retrieve his sound equipment, according to court records, and was confronted by Almena, who was angry because his toddler son had found a condom after the party.

“I explained things like that can happen at a large party,” Lewis later told police, according to records.

A shoving match ensued, in which Lewis said he was scratched and his shirt was torn, and a friend who was with him said his arm was pulled out of its socket. An Oakland police officer called to the scene later wrote in his report that he canvassed the building as part of his investigation; the report did not mention any unsafe living conditions or a do-it-yourself electrical set-up, he made no mention of them. From the records, it does not appear any arrests were made.

In a subsequent request for a restraining order against Almena, Lewis said Almena threatened to get a gun during the altercation and noted that there were “a number of bows and arrows” and a box of bullets on display in the warehouse, adding a dash of immediacy to the alleged threat.

“I am afraid this person might be unstable,” Lewis wrote on the form, which he signed Jan. 6, 2015.

Less than month later, Almena filed his own request for a restraining order. His target was a tenant, Shelley Mack, who Almena said refused to pay rent and was physically and verbally abusive.

Mack, 58, told The Times that in the winter of 2014 she paid $700 a month to live inside a trailer parked in the warehouse. She had been drawn to the space by a Craigslist ad promising cheap rent. Once there, she and several tenants — between 10 and 20, depending on the day — shared a single bathroom. The building had no heat, and in November 2014 a transformer blew, cutting off power.

“There was no electricity, and it was freezing in there,” she said.

For his part, Almena said Mack tormented him and his family. During one altercation, Almena said, one of Mack’s associates pulled a gun and chased him with it while Mack “robbed personal property,” according his request for the restraining order.

Almena said Mack also repeatedly called child protective services with false accusations aimed at having his children taken away.

Alameda County Social Services removed Almena’s children, then ages 11, 6, and 4, in March 2015, court records show. The reasons for the removal were not clear from the records.

Earlier this year, Almena’s wife posted photos on her Facebook page showing the family reunited.

Mack, who said she was never served with Almena’s complaint, denied the allegations Monday night.

Neither Almena nor Allison could be reached for comment by The Times.

For breaking news in California, follow @VeronicaRochaLA on Twitter.

ALSO

Oakland officials fielded multiple complaints about warehouse

Before deadly Oakland fire, Ghost Ship warehouse was scene of legal sparring and tenant drama

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.