Nancy Reagan dies in Los Angeles at 94: Former first lady was President Reagan’s closest advisor

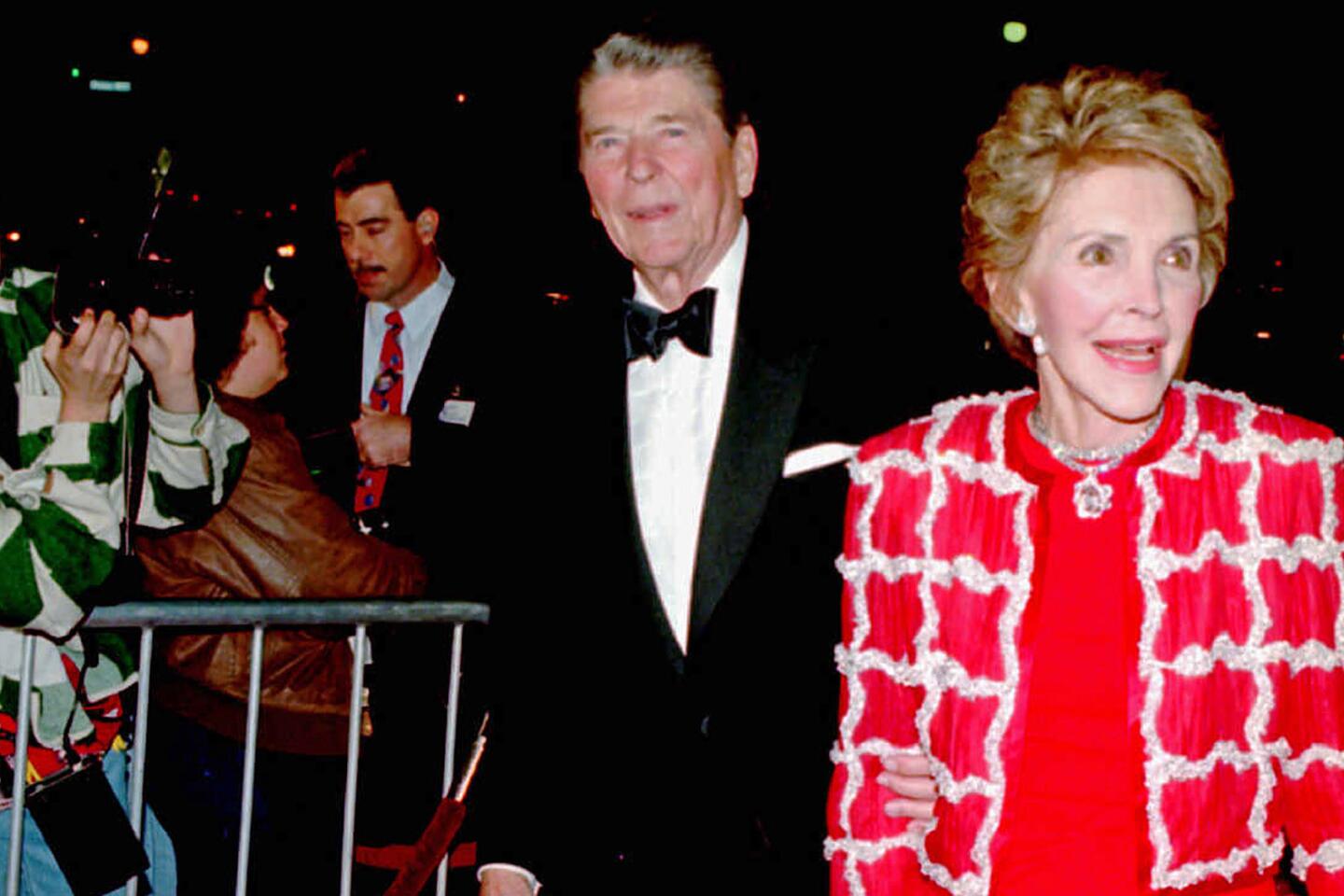

Former First Lady Nancy Davis Reagan, whose devotion to her husband made her a formidable behind-the-scenes player in his administrations and one of the most influential presidential wives in modern times, died Sunday of congestive heart failure, her office said. She was 94.

Although Reagan pursued some programs of her own as first lady, she considered her most important role promoting the political, physical and mental well-being of Ronald Reagan. Launching one of history’s most extraordinary partnerships with their 1952 marriage, she became his closest advisor, wielding her influence to defend his interests and advance his goals.

NEWSLETTER: Get essential California headlines delivered daily >>

Particularly tough-minded on the hiring and firing of key staffers and Cabinet members, she often played bad cop to his good cop, forcing difficult decisions that the famously easygoing chief executive was loath to make.

“Reagan knew where he wanted to go,” biographer Lou Cannon once wrote of the iconic California politician who became a two-term president, “but she had a better sense of what he needed to do to get there.” Nancy Reagan, Cannon maintained, “did more than anyone to help him get what he wanted.”

Former First Lady Nancy Reagan remembered.

One of the 20th century’s most popular presidents, Ronald Reagan, who died in 2004, was nicknamed the “Teflon president” because of his ability to deflect almost any controversy or criticism. But his wife was the “flypaper first lady,” as longtime advisor Michael Deaver once quipped, because nearly everything negative stuck to her.

She was lambasted for her opulent taste in designer clothes and redecorating the White House, particularly when she ordered $200,000 worth of new china for state dinners. Ridiculed for the reverential looks she gave her husband, she was the first lady feminists loved to disparage.

When she appeared to feed her husband a line at a news conference (“Doing everything we can” on arms control), she was accused of stage-managing the president. When her displeasure with White House Chief of Staff Donald Regan became front-page news and he was fired, critics called her a dragon lady.

A new legacy developed in the post-White House years, after her husband’s announcement in 1994 that he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, a degenerative brain disease. She devoted herself to his care, rarely leaving their Bel Air home where he was cloistered for the last decade of his life.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

Taking an unusual public stand against President George W. Bush, she also became a vocal advocate of federal funding for embryonic stem cell research, which Bush opposed despite scientists’ belief that it could lead to cures for incapacitating diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

Alzheimer’s eventually robbed President Reagan of the ability to recognize his wife, removing him to “a world unknown to me,” Nancy Reagan wrote in a letter to Bush. The disease had taken him to a world beyond speech and memories of the remarkable life they had shared, but she met the challenge with such grace and fortitude that the American people came to view her as “a human being,” historian Lewis L. Gould observed, “instead of a political caricature.”

Born in New York City on July 6, 1921, she was named Anne Frances Robbins, “but for some reason,” she wrote many years later, “I was always called Nancy.”

Her parents — Edith Prescott Luckett, a stage actress, and Kenneth Seymour Robbins, a car salesman — lived in a poor section of Flushing, N.Y. “It wasn’t a good marriage,” Reagan wrote in “My Turn,” her 1989 memoir, “and by the time I was born their relationship was so tenuous that Kenneth Robbins wasn’t even at the hospital.” When she was 7, her parents divorced.

She adored her mother, who led a glamorous life in a social circle that included some of Hollywood’s most famous names. Nancy grew up calling Spencer Tracy “Spence” and spent holidays at the home of another well-known actor, Walter Huston. But she also missed her mother, whose frequent absences for work meant Nancy had to stay with relatives.

Life improved when her mother met Dr. Loyal Davis, a divorced neurosurgeon from Chicago and a staunch conservative. When he married Edith in 1929, Nancy moved into their new home on the shores of Lake Michigan and enrolled in the exclusive Girls Latin School. When she was 14, she asked her natural father to give up his parental rights so that Davis could adopt her.

At Girls Latin, Nancy Davis discovered a passion for acting. She went on to major in drama at Smith College. After graduating in 1943, she returned to Chicago and worked as a nurse’s aide but kept up with acting by performing in summer stock.

Cast in a touring company of a play that took her to New York, she landed a small role in the Broadway production of “Lute Song,” a musical that starred Yul Brynner and Mary Martin. Her mother helped arrange a screen test overseen by distinguished director George Cukor that led to a contract with MGM at $225 a week. She moved to Hollywood and earned her first screen credit in “The Doctor and the Girl,” a 1949 drama starring Glenn Ford and Janet Leigh.

Over the next decade, she made nearly a dozen movies, usually appearing as a young or expectant mother. She dated some of Hollywood’s most eligible bachelors, including Clark Gable. But, as she would often say in later years, her life “didn’t really begin until I met Ronnie.” That meeting came about after she discovered her name in a Hollywood trade paper on a list of Communist sympathizers — no small concern in the blacklist era of the late 1940s. Apparently mistaken for another actress named Nancy Davis, she was advised to consult the head of the Screen Actors Guild. That was Ronald Reagan, who was recently divorced from actress Jane Wyman.

Reagan invited Davis to dinner to discuss the name problem. “I don’t know if it was exactly love at first sight,” the future Mrs. Reagan wrote years later, “but it was pretty close.”

After a two-year courtship, they were married at Little Brown Church in Studio City on March 4, 1952. Seven months after that, they started their family.

“During that year, we had Patti, who was born — go ahead and count — a bit precipitously but very joyfully, on Oct. 22, 1952,” Nancy wrote in “My Turn.” A son, Ron, was born in 1958.

In addition to her son and daughter, she is survived by stepson Michael, her husband’s adopted son with Wyman, and three grandchildren. Maureen Reagan, her husband’s daughter with Wyman, died in 2001.

Reagan wanted to quit work after she became a mother but continued to accept roles in TV and film because her husband’s acting career was in decline and they needed the money. She appeared with him in “Hellcats of the Navy” (1957).

When I say my life began with Ronnie, well, it’s true. It did. I can’t imagine life without him.

— Nancy Reagan

Shortly after that, he was hired by General Electric and crisscrossed the country giving speeches at GE plants and honing his conservative views.

In 1964, he gained national attention with a televised speech endorsing Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign. In 1966, he challenged California Gov. Pat Brown, a popular two-term Democratic incumbent, and won by 1 million votes.

For Nancy Reagan, a bruising political education commenced.

She was branded a snob for refusing to live in the governor’s mansion, a 30-room Victorian relic located on a truck route across from a motel and a gas station. In 1967, the Reagans decamped to a Tudor-style house with a pool in the Sacramento suburbs that some of their millionaire friends had purchased for $150,000 and leased back to them.

In 1968, writer Joan Didion interviewed Reagan in the new house, producing a piece for the Saturday Evening Post magazine titled “Pretty Nancy,” in which she portrayed the governor’s wife as a superficial woman who smiled too readily and who seemed to be “playing out some middle-class American woman’s daydream, circa 1948.” Reagan was deeply hurt by the story, which set the tone of coverage for years to come.

Her good deeds were barely noticed. She championed the Foster Grandparent Program, a cause she would continue to promote in Washington. She took a special interest in Vietnam veterans, hosting emotional dinners for returning prisoners of war and sitting at the bedsides of young soldiers at the veteran’s hospital in Westwood.

During her husband’s second term in Sacramento, she raised $1 million from Republican donors to build a new governor’s mansion on a scenic site above the American River in nearby Carmichael. When it was completed — not in time for the Reagans to live in it — critics found the 16-room, ranch-style residence architecturally deficient. Gov. Reagan’s successor, Jerry Brown, called it a “Taj Mahal” and chose a humble apartment for his residence. It was sold by the state in 1983.

When the Reagans moved to the White House in 1981, the new first lady followed the example of many of her predecessors: She redecorated. But unlike previous first ladies, such as Jacqueline Kennedy, whose refurbishing stirred little negativity, Reagan’s efforts were portrayed as evidence of insensitivity to the poor.

Television reports on the redecorating, funded by $800,000 in donations from wealthy Republicans, were juxtaposed with news of rising unemployment and homelessness. Reagan’s order of $200,000 worth of new White House china coincided with the administration’s decision to make ketchup a vegetable suitable for school lunches.

It did not help that Reagan’s wardrobe came from expensive designers such as James Galanos and Adolfo, who often gave her free clothes (for which she later sought tax write-offs). Nicknamed “Queen Nancy” by critics, she became a symbol of conspicuous consumption as a national recession set in. On late-night TV, Johnny Carson quipped that her favorite junk food was caviar.

“Virtually everything I did during that first year was misunderstood and ridiculed,” Reagan complained in “My Turn.”

When polls showed that she was dragging down her husband’s ratings, his advisors hatched a plan.

The centerpiece of their strategy unfolded at the White House press corps’ annual Gridiron Dinner in 1982. To the astonishment of 600 members of the media, the surprise guest performer was none other than the first lady, dressed like a bag lady in white pantaloons, yellow rain boots, a red housedress, fake pearls and a straw hat festooned with feathers and flowers. It was an appropriately tacky get-up for the song she sang, set to the tune of “Second Hand Rose.” Special lyrics by a White House speechwriter poked fun at her haughty image: “Even though they tell me that I’m no longer Queen, Did Ronnie have to buy me that new sewing machine? Secondhand clothes, secondhand-clothes, I sure hope Ed Meese sews.”

Her self-deprecating spoof won rave reviews in the next day’s newspapers. For much of the rest of her White House tenure, she enjoyed noticeably kinder coverage.

With new confidence, she formalized a longstanding interest in fighting drug abuse with the “Just Say No” campaign, aimed at the nation’s youth. She carried the message to television talk shows and schools across the country and sparked a grass-roots movement, with more than 5,000 “Just Say No” clubs launched in the United States and abroad and collaborations with such groups as the Girl Scouts and Kiwanis Club International. She also hosted two international conferences on the problem, including one at the United Nations in 1985.

Although experts would debate whether the program had any lasting effect, its impact on the first lady was measurable: By early 1985, she had higher poll ratings than the president. Her reputation within the White House was another matter. She had sharp words for any staffer she thought was serving her husband poorly. Reagan speechwriter Peggy Noonan said she hid behind a pillar when she saw the first lady coming.

“She was the personnel director of the Reagan operation, so to speak,” Stuart Spencer, a veteran political strategist who ran Ronald Reagan’s gubernatorial campaigns and was a prominent advisor in the presidential campaigns, told biographer Bob Colacello in 1998. “She wanted to know who was going to be around Ron and who they were. She made a lot of decisions about people coming and people leaving. She was right 90% of the time.”

She was widely credited with forcing the departures of several high-level administration figures, including Interior Secretary James Watt, Labor Secretary Raymond Donovan, Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler and two national security advisors, Richard V. Allen and William Clark.

The most public and acrimonious dispute involved Regan, her husband’s chief of staff during the Iran-Contra affair. When the news broke that millions of dollars Iran had paid for American military equipment had been diverted to the Nicaraguan contras, she blamed Regan for the scandal that engulfed her husband’s presidency and repeatedly urged the president to fire him.

When Regan finally was ousted in early 1987, New York Times columnist William Safire wrote a piece headlined “First Lady Stages a Coup” and said her “political interference” made her husband look weak. Regan took revenge in his 1988 memoir, “For the Record,” which disclosed the first lady’s reliance on San Francisco astrologer Joan Quigley. Reagan had long consulted astrologers but gave such advice more weight after March 30, 1981, when her husband was gravely wounded in an assassination attempt by John Hinckley Jr.

She admitted that consulting Quigley had been a “terrible mistake,” but what she regretted more, she later wrote, was “the enormous embarrassment I caused Ronnie. And now, of course, I realize that I was foolish to think it was possible to have any secrets in the White House.”

All in all, 1987 was a brutal year. Her husband had prostate surgery; she underwent a mastectomy after learning she had breast cancer; and her mother died.

The Regan controversy stirred debate over the proper role of a first lady, who has no constitutional or statutory duties, but she made no apologies.

“Did I ever give Ronnie advice? You bet I did,” Reagan wrote in her memoir. “I’m the one who knows him best, and I was the only person in the White House who had absolutely no agenda of her own — except helping him.”

During the Iran-Contra controversy, she backed the White House staffers who believed that the president needed to take responsibility for the crisis. She also arranged for influential figures — including former Sen. John G. Tower (R-Texas), who headed the commission that investigated the affair — to press the case with him in private.

Her remarks to White House speechwriter Landon Parvin helped shape the address President Reagan ultimately made, in which he acknowledged that the arms trade had been a mistake. Once he made that admission, the headlines quickly faded. The first lady, Cannon said in a PBS documentary years later, “rescued the Reagan presidency.”

She was often a moderating force in her husband’s administration. To the dismay of the president’s more ideological advisors, she played a key role in arranging a White House meeting with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin and urged her husband to meet with Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko before the 1984 election. She advocated a softer stance toward the Soviet Union, which her husband had famously labeled the “evil empire.”

Though the Reagans had campaigned under a banner of traditional family values, their own family was far from model. Nancy bore the brunt of the criticism.

To Michael, who came to live with the Reagans when he was 14, Nancy was the unwelcoming stepmother who wouldn’t give him his own room or include him when the family went to church on Sundays. To Patti, who used Davis as her last name to distance herself from her father’s politics, her mother was overbearing, high-strung and overly fixated on her father.

“My parents’ world has two people in it,” Patti wrote in 1992, and anyone else was “extra baggage.”

Reagan later acknowledged their pain. Writing in “My Turn,” she said that all four children “have felt at one time or another that Ronnie and I were so devoted to each other that there wasn’t room for them in our affections, and that they were somehow left out. That was never our intention, and if they sometimes felt that way, I am truly sorry.”

That she reveled in her role as Mrs. Ronald Reagan was undeniable. Her look of wide-eyed adoration, derided by the press as “the look” or “the gaze,” said it all. Almost from the day they met, she wrote, “Ronald Reagan has been the center of my life. I have been criticized for saying that, but it’s true.”

So his illness — what she called “a truly long, long goodbye” — was devastating.

His diagnosis of Alzheimer’s brought reconciliation with children Michael and Patti, who said that her mother’s lonely years of caring for her husband had softened her in many ways.

In 2014, she was photographed visiting her husband’s grave on the 10th anniversary of his death. Though in a wheelchair, she looked elegant in a cream colored pantsuit and earrings by a favorite designer, Kenneth Jay Lane.

Reagan told ABC’s “Good Morning America”: “I learned a lot from Ronnie while he was sick — a lot. I learned patience. I learned how to accept something that was given to you, and how to die.”

For some time before his death, he had not been able to recognize the woman who had been his soulmate for 50 years. But, as she later recounted, in his last moments he opened his eyes, which he had not done in weeks, and looked at her. She murmured, “That is the greatest gift you could have given me.”

Former Times staff writers Pamela Warrick and Claudia Luther contributed to this report.

ALSO

From the archives: As Ronald Reagan fades, Nancy takes on a new role

From ‘Diff’rent Strokes’ to high fashion, Nancy Reagan was giant of 1980s

Nancy Reagan: Visitors pay their respects at the presidential library in Simi Valley

Live updates: Nation mourns Nancy Reagan, influential former first lady, who died at 94

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.