When this farmworker shelter started taking in asylum seekers, it lost its biggest donor

The Our Lady of Guadalupe Shelter doesn’t seem like much, but for the migrant farmworkers who descend on this impoverished desert town, it’s a welcome retreat from the fields and dirt parking lots they once called home.

In this renovated grape packing plant in the eastern Coachella Valley, farmworkers rise before the sun, wipe thin foam mattress pads with a rag sprayed with disinfectant and rest their folded black cots against the walls of what used to be the walk-in refrigerator.

Outside, illuminated by a half moon, they rummage through metal lockers that will store their lives for the next several months, packed almost to bursting with towels, blankets, clothes and dirt-caked boots

The shelter was started a little over a year ago, thanks in large part to hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations from Mary Ingebrand-Pohlad. It was her way of meeting a dire need for the farmworkers, who pick table grapes, lettuce, bell peppers and other crops.

But late last year, she grew concerned about asylum seekers being welcomed there.

Fearing that the focus had shifted away from the farmworkers, and that the new migrants could draw immigration enforcement to the shelter, Ingebrand-Pohlad decided in November not to renew her contribution. The move created an uncertain future for those who have been trickling in over the past few weeks in preparation for the grape harvest.

Her decision raised unusual questions about the mission of helping immigrants — and just which immigrants, exactly, even if they were bound by shared cultures and languages and dreams.

“I felt that we weren’t helping the people we set out to help and the mission had really changed,” Ingebrand-Pohlad said. “I cautioned the board that I was not in alignment with this new mission of taking anybody who knocks on the door. Whether they’re worthy or not — that wasn’t the point.”

Gloria Gomez, founder of the Galilee Center a non-profit that runs the shelter, said there weren’t many farmworkers around the time they began taking asylum seekers, with the peak harvest season being May through July. Although Ingebrand-Pohlad did not want the shelter to take in asylum seekers, “it’s my mission to receive every human being that comes to my door,” Gomez said.

The Diocese of San Bernardino gave the shelter funding for January and February, and the shelter took in 1,098 asylum seekers over those two months. When the diocese was unable to provide funds, the shelter stopped taking in asylum seekers. The Galilee Center relies on donations.

“If we had the money we would continue doing it, but we don’t have the money,” Gomez said. “Now I don’t have asylum seekers and I’m running out of money for our farmworkers.”

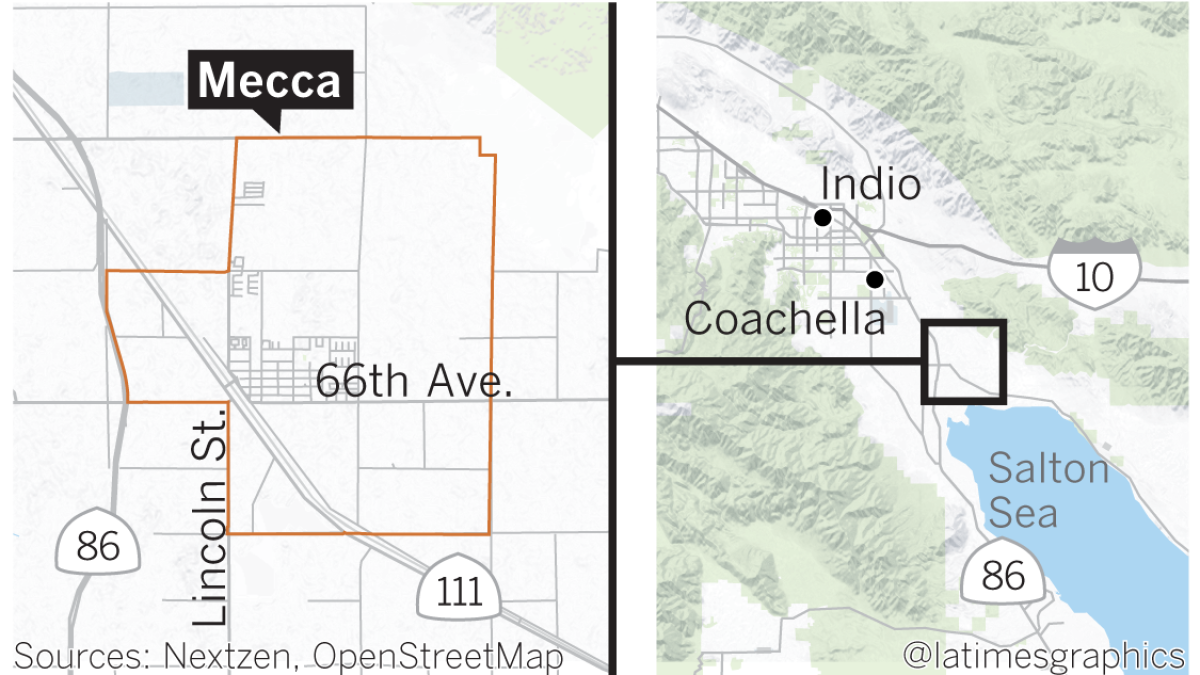

At 5 a.m., Mecca is a hive of activity, as farmworkers trek out into the dark to begin their day. Many get into trucks or hitch rides with friends to the fields, jamming up desert roads.

At markets near the shelter, foremen fill orange jugs with water for the day to provide for the laborers. Small groups clump together at Leon’s Meat Market, taking a chance that a foreman might need one of them for the day.

Among those at the market is Jesus Lara, 62, who spent the morning sitting in his car, waiting for the Our Lady of Guadalupe Shelter to open around 1 p.m. He had been working in the vineyards for two days before he was told not to come in because the vines were getting sprayed.

He sat in his black car, his skin weathered from the sun and his boots almost black from the dirt that cakes them. Seagulls paced the parking lot, a place Lara has slept many times in the more than 20 years he’s been coming to Mecca.

“We’re used to sleeping like dogs on the ground — because that’s how we lived for many years,” Lara said. He recalled times where he bathed in canals.

Since the shelter opened, he has spent his nights there.

“If they close it, it’s back to the ground again,” said Lara, who traveled to Mecca from San Luis, Arizona where he lives. “Back on the cardboard.”

The unincorporated town, a literal mecca for migrant farmworkers, has long struggled with how to house men and women arriving from across the country and south of the border to work in the vast farmlands. In 1992, Cesar Chavez chose to kick off a higher-wage campaign here, citing the workers’ abysmal accommodations.

"The housing conditions here in the Coachella Valley are some of the worst I've seen anywhere," Chavez said at the time.

Although apartments for farmworkers have sprung up around the Coachella Valley, beds tend to fill up fast, leaving many farmworkers struggling to find a place to sleep at night. Some cannot afford the rent on a room and even when they can, they often have no air conditioning or a place where they can cook.

Many farmworkers spend their nights sleeping in a parking lot, only visible to passersby as shadows moving in cars or campers. Others live in trailer parks.

“Housing is tough to come by for these folks,” said Javier Lopez, director of community relations for the Coachella Valley Housing Coalition, a non-profit developer of affordable housing. “Whatever is out there is good for these folks, because otherwise they’re going to be sleeping in their cars, on the sidewalks, under the trees and in the fields.”

Nearly two years ago, a Desert Sun story about the lack of housing for migrant farmworkers caught Ingebrand-Pohlad’s attention. The Galilee Center, which for years provided farmworkers a place to shower, wash their clothes and get a hot meal, wanted to open an overnight shelter but didn’t have the budget for it.

The article haunted Ingebrand-Pohlad, who has volunteered teaching English, reading and art in Thermal and Coachella for more than a decade. She decided to donate to the Galilee Center for the shelter and indicated she was willing to pay for operating expenses for the next couple of years.

The overnight shelter opened its doors in December 2017. Last year, Ingebrand-Pohlad said, an average of 90 people a night slept there.

Then, in November, she learned that the Diocese of San Bernardino had asked the shelter to help take in asylum seekers until they could get bus tickets to go to family members across the country. That month alone, the shelter took in 364 people.

Ingebrand-Pohlad called the situation “heartbreaking,” but expressed concerns that immigration officers dropping off asylum seekers — who have become particular lightning rods under the Trump administration — would deter farmworkers, some of whom are undocumented, from staying there.

Eventually, she made it clear that she would not renew her commitment to the shelter if it continued, she said. Before the month was over, she recused herself from the first and only board meeting she attended.

“The mission was derailed. We were no longer able to serve the people we set out to help, and that to me is tragic,” Ingebrand-Pohlad said.

Caught in the middle are the farmworkers.

When the sun is in retreat, they leave vineyards where they’ve spent the day en el deshoje — the removal of leaves from grape vines. The cold had set everyone behind and many are waiting to be called into work.

Outside the shelter, the farmworkers’ huaraches scraped against the asphalt as they lined up outside of a former maintenance room that has since been turned into a kitchen. The workers heaped their plates with carne asada, pico de gallo and tortillas and the men plopped down at picnic tables nearby.

After dinner, Jose Luis Castro clutched his flip phone to his ear, listening intently as his daughter mentioned his granddaughter’s upcoming first communion. He told her to make a nice dinner, something to celebrate the occasion he’d be missing.

Castro, a lawful permanent resident, got to the shelter less than a month ago and has been waiting ever since to begin harvesting chiles. The 66-year-old, originally from the Mexican state of Michoacán, has been coming to Mecca since 1993 and has slept wherever he could, in small rooms with no air conditioning, in heat that at times reached 110, and sometimes on the ground with dozens of others.

“If we didn't have this shelter, we’d stay outside, underneath a tree,” Castro said. “This place is perfect — beautiful.”

By 7 p.m., staff begin arranging the black cots around the gymnasium-style room, where a TV often features either soccer matches or telenovelas. Nine men are staying the night.

They share stories of young children they left had behind in Mexico and of birthdays they celebrated before setting off for California, knowing they’d be deep in the harvest by the time the day came. By now, the men have adjusted to the distance, knowing that the money they make chasing the seasons will help their family more than what they will make back home.

On this night, many of the men were asleep by 8 p.m., but outside, at one of the tables, Ricardo Olvera Martinez made a video call to his family in Mexicali, although he knew he should be sleeping already.

“Dónde está mi niña?” he called out, asking for his daughter who is nearly two. He called her “amor,” trying to hold her attention long enough to catch a glimpse of her face. When he saw his 14-year-old son, he asked him about school as he tapped his foot against the concrete. As he spoke to his family, he rested his head in a hand, telling his wife that he was tired — followed by a quick “everything is fine.”

He broke out in a smile often, taking a screenshot of the video chat, something to remember them by. When he told them he was heading to bed, his wife told their daughter to say goodbye.

“Adiós, amor,” he said, throwing up a hand to wave to his daughter. Bye, my love.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.