Fresh out of prison, a former lifer finds his footing training for the L.A. Marathon

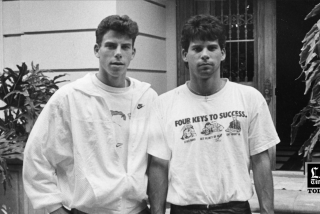

In a photo taken during his murder trial, Gilbert Anthony Romero’s face is blank, expressionless. Though he had pleaded guilty to first-degree murder and attempted murder, he hadn’t apologized or shown remorse. It would take decades for him to show — or even feel — remorse.

The judge in a San Bernardino courtroom sentenced Romero to life in prison. The year was 1991. Romero was 19.

Joyce Bright, the mother of his victim, explained in a letter to the San Bernardino County Sun why she favored a sentence of life in prison. “At one time, I would have said ‘death,’ but God said, ‘Vengeance is mine.’”

She added: “He will come up for parole in about 29 years. I pray he never gets out.”

On an early Sunday morning in January 2019, a dozen people gathered in the lobby of Beit T’Shuvah, a rehab facility in west Los Angeles. They were dressed in running gear, and a coach handed out slips of paper. “You all have course maps?” she asked.

Among the runners was Romero, now 46. He bounced in place, shifting his weight from one foot to the other. White socks partially covered tattooed calves. He wore a white bandanna.

Romero was released on parole last September. One of his goals now that he’s on the outside: run the Los Angeles Marathon — all 26.2 miles.

The 34th Los Angeles Marathon gets underway early Sunday »

He trained with the team at the Jewish faith-based rehab center, where he lives as part of his alternative sentencing. Many on the team, Running 4 Recovery, are working to beat addictions: drinking, gambling, hard drugs.

Training as a team gives members two main things, said coach Leslie Gold, who founded a nonprofit group to bring running to rehab patients: self-confidence, and a sense of connection and camaraderie.

“Finishing the marathon means something different to each person,” she said. “You cross the finish line and get a medal placed around your neck, and you have a symbol of something you accomplished, that’s going to stand for what you’re capable of.”

After she gave the word, Romero and the others filed out to the sidewalk. He’s an athletic guy who played handball and soccer in prison, but he’s a novice runner. He broke into a jog.

Later, he was still jogging steadily as team members shouted encouragement. After 14 miles, he crossed an imaginary finish line and slowed to a walk. Gold and another runner slapped him high fives.

Running a marathon is something Romero never thought he would do. That’s why he’s doing it. It’s a step forward. A step away from his past.

Looking back now, Romero knows the moment his life took a dark path, when he went from a shy kid, playing alone with Star Wars action figures, to someone filled with rage. He was 11.

Romero was raised by a single mom in Whittier, and she tried to bring him up right. She took him to the library, to the park, to museums. She also took him to church, and some of his happiest childhood memories are from there.

He was 9 when his mom gave birth to a boy she named Isaac. Isaac was born with severe brain damage, and Romero prayed, with a child’s simple faith, that God could do anything: “Please heal my brother.”

When Isaac died suddenly, his mother went into depression, and Romero got angry — he began to hate God.

It was then, at age 11, Romero said, that he started getting high and drunk with a relative.

Soon he was hanging out with older kids. Soon he was doing speed, then dealing speed. Soon he was breaking into cars, getting into fights, robbing houses.

Still, he managed to avoid trouble with the law. He graduated high school and got a job at a grocery store.

But by 18 he was deep into a life of addiction, crime and selfish actions taken with no consequences. Until one Friday night in 1990.

It was after midnight on Oct. 6 when a Volkswagen Beetle tore down a residential street in Rialto. Romero was behind the wheel and his best friend, Hector Komiyama Jr., sat in the passenger seat with a .22-caliber rifle.

The car barely missed two pedestrians. One was Razzael Bright, 13. According to various accounts of what happened next, he yelled out something like, “Hey, what are you trying to do?”

The car turned around and drove back, its lights off. Razzael exchanged words with the men. A shot rang out. Police said the bullet pierced Razzael’s heart.

That was just part of the violence they unleashed that night. Three other people were shot. The shootings weren’t gang-related or robberies. Just random violence.

Razzael’s older brother, Raphael Bright, was 22 when his brother was killed.

“This is something that’s been on my mind, on my conscience, on my soul, for 30 years,” he said recently. “Mr. Romero doesn’t have any idea of what fractured our family forever in so many ways.”

The pain of losing Razzael was compounded, Bright said, by the disrespectful behavior and lack of remorse shown by Romero and Komiyama, who fired the fatal shot and also was sentenced to life.

Bright’s voice broke as he recalled: “Razzael Kenny Bright, a dynamic young man; a character to behold; a lot of creativity. The world lost a good young human being on that day; that Friday night. He was my little brother.”

For his first decade behind bars, Romero continued the lifestyle he was accustomed to: alcohol, drugs and violence.

“I had no hope,” Romero said recently. “I was never supposed to get out.”

It wasn’t until 2002 that Romero decided, at age 30, that he felt the need to take control of his life — to stop being a follower who tried to please others. He took classes: Criminals and Gang Members Anonymous, Life Skills, Cage your Rage, Celebrate Recovery.

“I was broken,” he said. “You buy a box of a puzzle, shaken up, and that was me. I wanted to figure out what was wrong with me, take each individual piece, put it back together.”

One piece of the puzzle was empathy. Romero felt nothing after Razzael’s death, but when his grandmother died in 2004, he realized he had never been able to say “I love you” one last time.

“That was the first moment I really got to feel what Razzael’s family felt,” Romero said. “That was my moment when the light bulb went on and was like, ‘This is what you denied that family.’ That’s when I started getting in depth with taking responsibility, trying to feel empathy and remorse for what I did.”

Now he thinks about his friend in the passenger seat with the rifle and wrestles with the question: “Why didn’t you stop him?”

A few years ago, after classes had helped Romero better understand himself and his past, he wrote letters to the people shot that night in 1990: to James Cardey, Perry Reyes, Roberto Ruiz, and to the family of Razzael Bright.

“It hurt,” he said. “It hurt to write these letters because I was feeling remorse. It hurt that I had to put these people through hell for no apparent reason. That’s the thing, for no reason. I terrorized these people for no reason.”

He wrote to apologize for what he had done. He doesn’t know if they ever received the letters.

“I’m not asking for forgiveness,” he said in an interview. “How can you…” his voice trailed off. “I wasn’t going to do that. All I could say was I’m sorry for who I was.”

When he was 18, Romero said, he was arrogant, selfish, greedy and violent.

“I am not the same person I was back then,” he said. “I can’t even say I was a person back then. I have to call myself a monster.”

Romero’s chance for freedom came in 2015 with the passage of a new law giving youth offenders a chance at parole. He was rejected on his first attempt in 2016, but last year the parole board granted him his freedom.

Romero has been struggling with a sore ankle, but he’s been back at training and is determined to finish the marathon Sunday — “even if I have to crawl.”

Sometimes, during a long run, he questions why he is plodding down the street. Then he feels the sun on his face, the wind in his hair. He looks about and soaks it all in; feels immensely grateful for it. All of it. The trees, the sky. Even the buildings.

He’s found work as a machinist and plans to move out of Beit T’Shuvah soon.

As he tries to rebuild his life, he said, he will carry a piece of Razzael Bright with him.

“The only thing I can do is try to honor his life,” Romero said. “Me doing the positive things, talking to youngsters, trying to help them — doing positive things wherever I can, being in service to whoever I can, that’s showing some kind of honor to Razzael — ‘You did matter. You’re not forgotten.’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.