Reaching inside the jails to break the cycle of homeless arrests

A door opened, and three men walked out of captivity into a sun-drenched waiting area. It’s a scene repeated hundreds of times a day at Los Angeles County Men’s Central Jail.

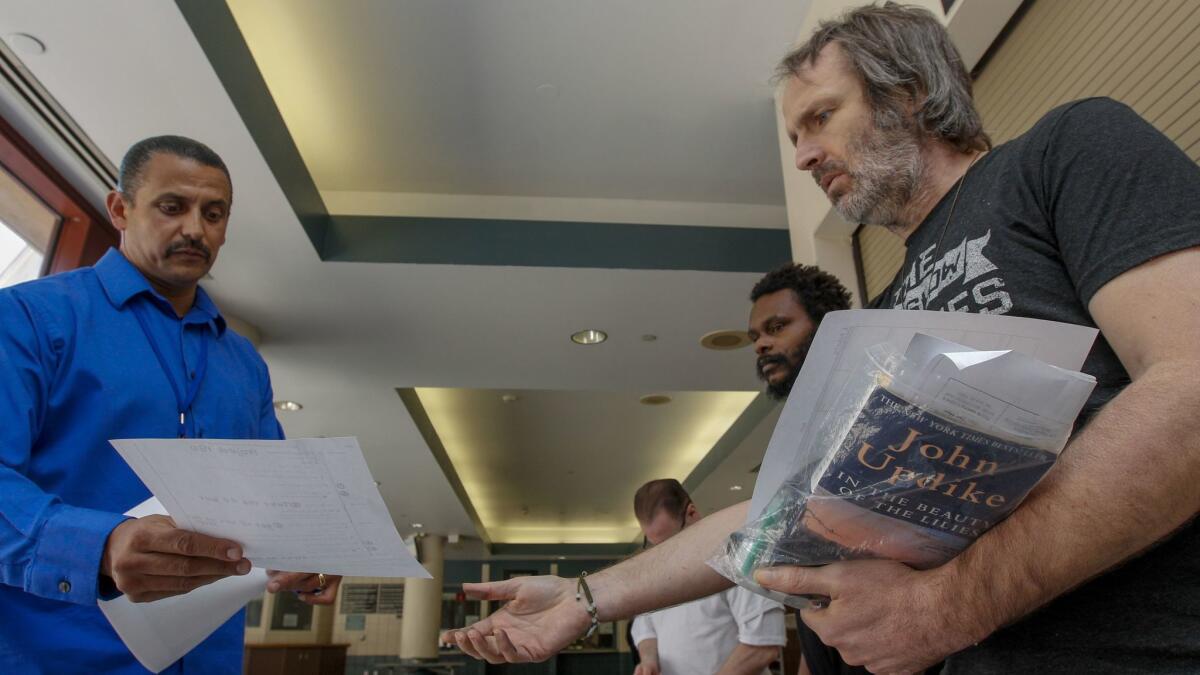

But instead of being greeted by family members and friends, these men were met by Victor Key, a case manager for Project 180, a downtown agency that is on the front line of a homeless strategy called jail in-reach.

The three men had been arrested for felonies. A psychiatrist had diagnosed them with mental illnesses that contributed to their crimes.

All agreed to take a step that could end years of homelessness and incarceration. As a condition of probation they would enter an interim housing program designed to lead to permanent housing. It’s part of a new effort by Los Angeles County aimed at breaking the cycle of incarceration among the mentally ill and substance abusers. By providing a small percentage of homeless being released from jail a path other than back on the streets, officials hope to reduce the chronic recidivism that has long plagued this portion of the homeless population.

In a region where homelessness is on rise and solutions remain vexing, the program is being closely watched and has received an infusions of both public and private money.

After a quick briefing, Key led them across the street to a van. Thirty minutes later, they walked into a freshly painted gray and orange building on West Vernon Avenue, a recently opened crisis housing center run by First to Serve Outreach Ministries.

The men were assigned bunks in one of the shelter’s mini-dorms, each holding four to eight men or women. That would be their home for three to six months while case managers worked with them to acquire permanent apartments with medical and mental health support.

Their choreographed release from jail was arranged by the Office of Diversion and Reentry, an agency within the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services Although it does not directly target homelessness, the inmate housing program contributes to the county homeless initiative because its clients are generally also homeless.

The Office of Diversion and Reentry grew out of L.A. County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey’s 2015 report “Blueprint for Change,” addressing the treatment of the mentally ill by law enforcement and the justice system.

“Our jail should not be used to house people whose behavior arose out of an acute mental health crisis merely because it is believed — whether correctly or otherwise — that there is no place else to take that person to receive treatment instead,” the report said.

The county Board of Supervisors created the office in November 2015 and funded it with $100 million to start and $30 million annually. Besides jail in-reach, the office also operates sobering centers and recuperative centers for homeless people leaving hospitals.

The office contracts for interim beds across the city and can draw on the county’s flexible housing subsidy pool to place 150 former inmates into permanent housing each year.

The program’s capacity will soon more than double. In October it received a $10-million commitment from organizations including the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation and UnitedHealthcare to subsidize housing for 250 more a year for four years.

Under a funding model called Pay for Success, the sponsors are lending the money to the county and will be reimbursed if the program meets its recidivism and housing retention goals. At the end of the contract the county will be responsible for maintaining the subsidies.

Since last fall, when jail intake officers began recording housing status, about 190 inmates entering the jail each week have declared themselves homeless. Until recently, they would cycle through the jail like other inmates and ultimately be released to the streets.

Currently, the Office of Diversion and Reentry deals with a small portion of that population: inmates who have been diagnosed in jail with a mental illness or substance abuse disorder.

The program’s medical director, Kristen Ochoa, a psychiatrist, identifies candidates for community treatment and then petitions the court for their release with a requirement that they stay in treatment.

Ochoa started out small in 2015 focusing on misdemeanor offenders found to be mentally incompetent to stand trial.

Unlike other defendants, they do not get speedy trials, do their time and get out. They receive treatment from the jail’s psychiatric staff and remain locked up until they are found to have regained their competence. Those who don’t are held for the maximum sentence for their alleged crime, usually six months to a year.

Ochoa has now obtained conditional releases for more than 500 such inmates. They remain under court jurisdiction until their maximum sentences expire, returning regularly to mental health court for progress reports.

There, Superior Court Judge James Bianco addresses each in a fatherly way.

“Wow, you’re doing great! I’m so proud of you,” he told one during a court hearing earlier this year, then quickly changed tone for the next.

“I want to remind you about how badly you were doing,” he told a woman who was balking at taking medication. “The last thing I would want to happen to you is to find you in the same condition as when you were in jail.”

Last summer, the Office of Diversion and Reentry launched a supportive-housing program for a larger population of inmates, including alleged felons who were competent to stand trial but still diagnosed with a mental illness.

After receiving referrals from jail mental health staff, judges, attorneys or custody assistants, Ochoa diagnoses each and recommends those she thinks would do well in treatment.

Prosecutors and defense attorneys review the recommendation. If they agree, they reach a plea deal with treatment as a condition of probation. Case managers then pick up the inmate for the “warm handoff” to the residential facility.

More than 700 inmates were referred for diversion from August through September, said Corrin Buchanan, the program’s interim deputy director. About 200 were in interim housing and 98 had obtained permanent homes.

Not all of the cases end well. Of the three inmates released to First to Serve that spring day, one remains in interim housing and one is now living in his own apartment, said Emily Bell, Project 180’s director. The third left the program and has not stayed in contact with a case manager.

It is too soon to judge the program’s overall success because recidivism rates are measured on two years of data, Buchanan said. A formal evaluation will be done by the Rand Corp., examining changes in substance abuse, recidivism and use of public services.

So far, the two diversion programs have reached only a small percentage of homeless inmates. That is changing.

In July, the Board of Supervisors committed about $3.3 million over three years from Measure H to contract with four agencies, including Project 180, to do case management in the jail. It will pay for 12 case managers, four social workers and four sheriff’s custody assistants

For now their goal is modest — making sure that every homeless inmate is entered in the database used by social agencies across the county to prioritize people for housing. Despite past encounters with case workers, few of them are in the database, outreach workers with Project 180 say.

Homeless people in encampments are often reluctant to answer questions on the street but have an incentive when they’re in jail.

“For the most part it’s hope,” said case manager Larry Gray. “I remind them of the history of their homelessness. I had a guy last week who broke down in tears. Just the thought of having the opportunity to have housing, really made him more engaging and more willing to participate in the survey.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.