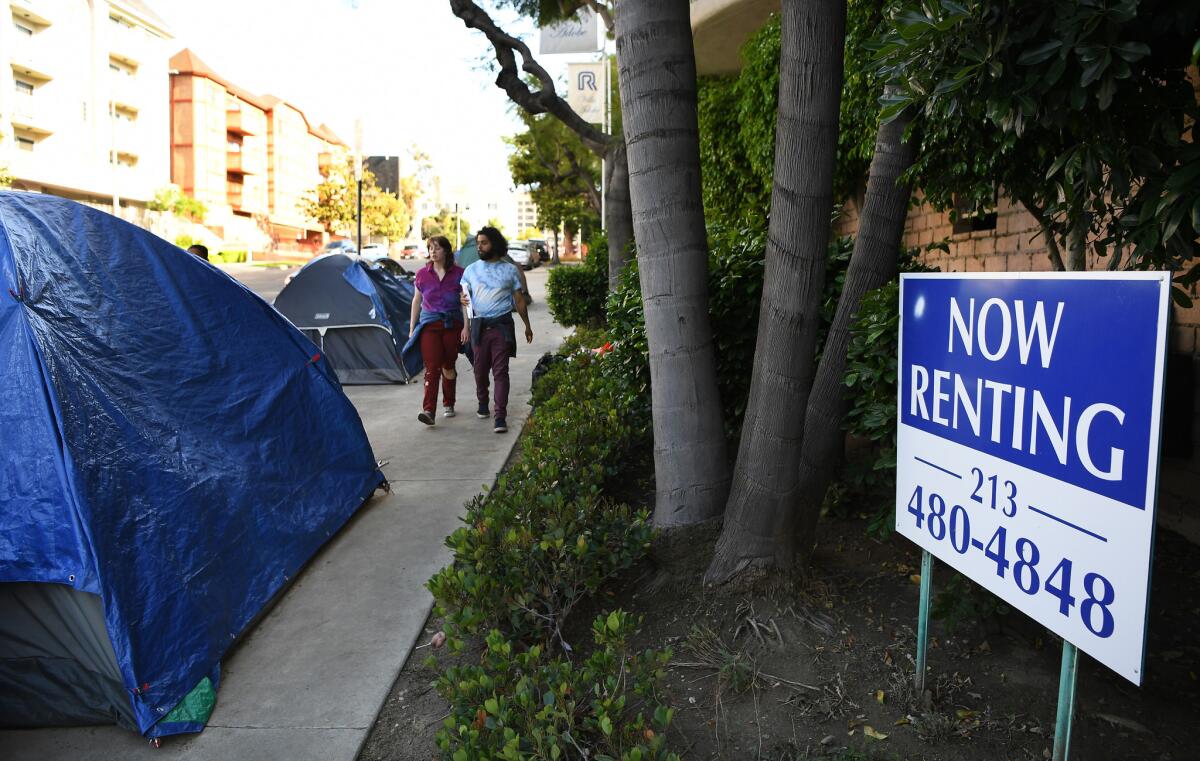

L.A. is swamped with 311 complaints over homeless camps. But are the cleanups pointless?

Austin Yi said he couldn’t take it anymore. Noise from the tents along Shatto Place rose to his third-floor Koreatown apartment at night: yelling, screaming, the clanging of tools as people repaired bikes.

When he couldn’t drown out the racket with white noise, the 27-year-old and his wife would drag blankets into the hallway to sleep on the floor. Yi regularly lodged complaints through the city’s 311 system.

“At first I had so much sympathy,” he said, recounting the times he had handed over money or offered to buy food. “Now it changed me. … I wish they would just go away.”

Around the corner from Yi, Fernando Alvarado lamented the items he lost to city sweeps of homeless encampments: his shoes. His identification card. A blanket to ward off the night chill.

The latest sweep, Alvarado said, happened two weeks ago. But he and a few others quickly camped out again in front of a vacant lot on Westmoreland Avenue.

Los Angeles has been deluged with requests to clean up homeless encampments in recent years. Between 2016 and 2018, such requests shot up 167%, according to a Times analysis of 311 data. The trend has continued this year, with requests up 37% in the first few months compared with the same period a year earlier.

The surge in cleanup requests has happened as L.A. and other cities have seen hefty increases in the number of people without permanent shelter. The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority announced Tuesday that the homeless population had jumped by 16% in the city and 12% across the county. Most — 75% — were living outdoors, including in vehicles.

City officials say they have relied on complaints to plan cleanups, in part, because there aren’t enough crews to regularly clean the entire city. Homeless activists have denounced that method as arbitrary and are calling for an overhaul of a system they decry as dehumanizing and wasteful.

As complaints have surged, L.A. politicians have faced competing pressures from activists, business owners and residents, spurring fresh soul-searching at City Hall about the sweeps. City Councilman Mike Bonin, whose coastal district includes the homeless hot spot of Venice, recently declared that “it is nearly impossible to find anyone who is satisfied with the result.”

The Times identified more than 100 locations where calls and other 311 service requests became so persistent that the city was responding to complaints weekly for at least five weeks in a row. Such cycles have occurred from the West San Fernando Valley to Venice but were most common downtown, in Hollywood and Koreatown.

One such place is the short stretch of Shatto Place where Yi used to live, around the corner from where Alvarado beds down. The city fielded 172 requests there in just a year and a half.

At the apartment complex that Yi left, property manager Samantha Son has urged tenants to lodge complaints with the city and tracked requests with a spreadsheet. Son worries that the encampments alongside the building are driving away prospective tenants — even though the number of tents has declined in recent months.

“Whenever the people come to visit, they like the unit inside,” said Son, who lives on the second floor. “But then they see the outside and don't come back.”

Across the street, the Rev. Gonggun Hwang has heard his congregants complain that they feel unsafe walking to and from the Won Buddhism of Los Angeles temple. One homeless man routinely slept outside the temple’s doors, and Hwang said he has had to repeatedly clean up urine and feces.

“As a Buddhist, I didn’t really want to bother them,” Hwang said. “But I couldn’t help but do something.”

For a while, he turned to 311 to complain. The tents dwindled at times, but didn’t disappear.

Now “I understand they got nowhere to go,” Hwang said. “So I gave up.”

Homeless encampments are only a small fraction of the 311 requests fielded by the city, which are topped by demands to pick up bulky items and clean up graffiti.

But it is the fastest-growing category and presents the city with an expensive and bedeviling challenge. The city budgeted more than $30 million this fiscal year for homeless encampment cleanups and is planning to spend nearly $40 million in the coming year, according to city officials.

A coalition of activists called Services Not Sweeps has launched a campaign to push Mayor Eric Garcetti to scrap the city’s existing system, saying that cleanups shouldn’t be triggered by complaints but be regularly scheduled so homeless people can prepare. They want bins and trash bags provided to people so they can throw out trash before city crews arrive. And they don’t want police on the cleanup teams, as officers are now.

“We can have a system that treats homeless people like something to be cleaned up … or one that deals with the reality that we’re facing,” said Mike Dickerson, an organizer with Ktown for All, a grassroots group that assists and advocates for homeless people in Koreatown and is part of the Services Not Sweeps coalition.

Even some of the people who dial 311 — like Hwang at his temple — are uneasy about the process. Many homeowners and business owners, in turn, are frustrated that the cleanups seem to do little, complaining that tents and trash come back after each sweep.

“Last Tuesday they cleared out, disinfected, painted the side of our building — and by 1 o’clock they’d all moved back,” said Mitch Blumenfeld, vice president of a South L.A. business that sells mannequins, shelving and other fixtures for stores.

“Then Wednesday, we had a fire. What’s going to happen when a building like this goes up in flames and they lose all the revenue?”

Complaints to 311 trigger a step-by-step process: City workers visit the location identified by the requester to check whether it is really a homeless encampment or just some abandoned items, according to the Bureau of Sanitation. At hot spots like Shatto Place, the city checks on requests in batches on the same days that trash is collected.

Source: data.lacity.org

Rahul Mukherjee / Los Angeles Times

If sanitation workers find a mattress or a couch, they can pick it up and reclassify the complaint as a “bulky item” request, according to the department. Hundreds of other complaints are closed on the day of the assessment without a cleanup.

But if homeless people are present, the Bureau of Sanitation needs to get additional approval for a cleanup, including a sign-off from the Homeless Services Authority after it has done outreach. That can take as long as three weeks, according to the city.

“If I could do it quicker, I would. But that outreach component has to be there,” said Jose “Pepe” Garcia, assistant general manager for sanitation.

He added that unlike abandoned couches, homeless camps cannot simply be carted away. L.A. has repeatedly been sued for violating the rights of homeless people, and last year, a federal appeals court ruled that homeless people cannot be punished for sleeping on public property if they have no access to shelter.

On a gray morning, Darryl Dolberry and other members of the authority’s Homeless Engagement Team stopped along a spartan stretch of Alameda Street and 41st Place in South L.A., checking whether anyone was home at a makeshift shelter of tarps and plywood alongside a drab industrial building.

The surge in cleanups has pulled workers such as Dolberry away from their regularly scheduled efforts to proactively reach out to homeless people in assigned neighborhoods, rerouting them to sites slotted for cleanups so they can try to help people before city crews arrive, said Heidi Marston, the chief program officer for the homeless authority.

Dolberry called out and knocked, but no one was there.

The makeshift shelter was the home of Rickey Harris, who later said he had lived on the street for years. Before becoming homeless, Harris said he used to remodel houses in the neighborhood. Now he scrapes by making money with recycling and doing odd jobs.

He had no interest in going to the shelter suggested by outreach workers, saying he might not even get a spot if he went.

Nearby, a flier posted on a telephone pole warned that a cleanup was coming in a few days. City workers are supposed to post a flier 24 to 72 hours in advance, telling homeless people they will have to remove their belongings.

Homeless people also can face “rapid response” teams, which enforce rules against keeping too much personal property on the sidewalks. And if they camp out on private property, they can be ejected without the same warning.

Critics argue that relying on 311 complaints can politicize the cleanup process. In one case publicized by Adrian Riskin, a blogger on MichaelKohlhaas.org, Garcetti aides asked police officials via email to make sure a South L.A. encampment was cleaned up before the mayor visited a construction site in the area.

“There's no attempt at having a plan, so they can use their resources to actually address the problem,” Riskin said. “It looks like it’s a political tactic.”

Garcetti spokesman Alex Comisar said the emails “do not reflect the mayor’s approach to interacting with Angelenos experiencing homelessness, and he was unaware of this exchange.”

Days after the flier went up on the street where Harris lived, nearly a score of city workers arrived at 41st Place to clear his shelter. They came with a trash truck, a flatbed loaded with supplies for a hazardous-waste team, and a front loader to remove trash piled high on the street — some of it likely dumped by local businesses. Police officers blocked the street with their squad cars.

This was all for one man’s ramshackle home.

“Until they find the adequate housing, I’m responsible for who and what is out here,” Garcia said as he watched his crew load broken pallets into a trash truck.

Harris bundled some clothes and other belongings into shopping carts and rolled them over to the next block, where he pulled out some cushions and shut his eyes against the morning cold.

“I couldn’t sleep last night, knowing they was coming,” he said after waking. Yet he was calm, even philosophical. “Ain’t nothing I can do about it. All that negativity pulls all the positive energy.”

A block away, four people in white protective suits and face masks cut back the tarps that covered his home, revealing the things he had left behind: a bed that was made, a pile of folded clothes, instant coffee, a container of Vick’s Vap-O-Rub, rubber sandals, mini flashlights and a Granny Smith apple.

When Harris returned later, it would all be gone, either tossed out or stored elsewhere.

As he chatted with reporters, a young couple greeted him. One neighbor paused in his truck, waiting for Harris to wave. If he doesn’t stop by a local truck for coffee or a breakfast sandwich, Harris said, people ask him, “What’s wrong?”

“I wouldn’t want to move out of this neighborhood,” he said.

Days later, he was back at the same spot where his shelter once stood, sleeping on a cushion flanked by shopping carts.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.