Q&A: ‘Godzilla’ El Niño: Unbelievable rain for California, dry winter for Midwest

We’ve heard that a “Godzilla” El Niño could be coming this winter and could help bring some relief from California’s punishing four-year drought.

But what do Godzilla El Niño winters really mean, based on past experience? Let’s take a look.

1. Unbelievable rainfall in a short amount of time.

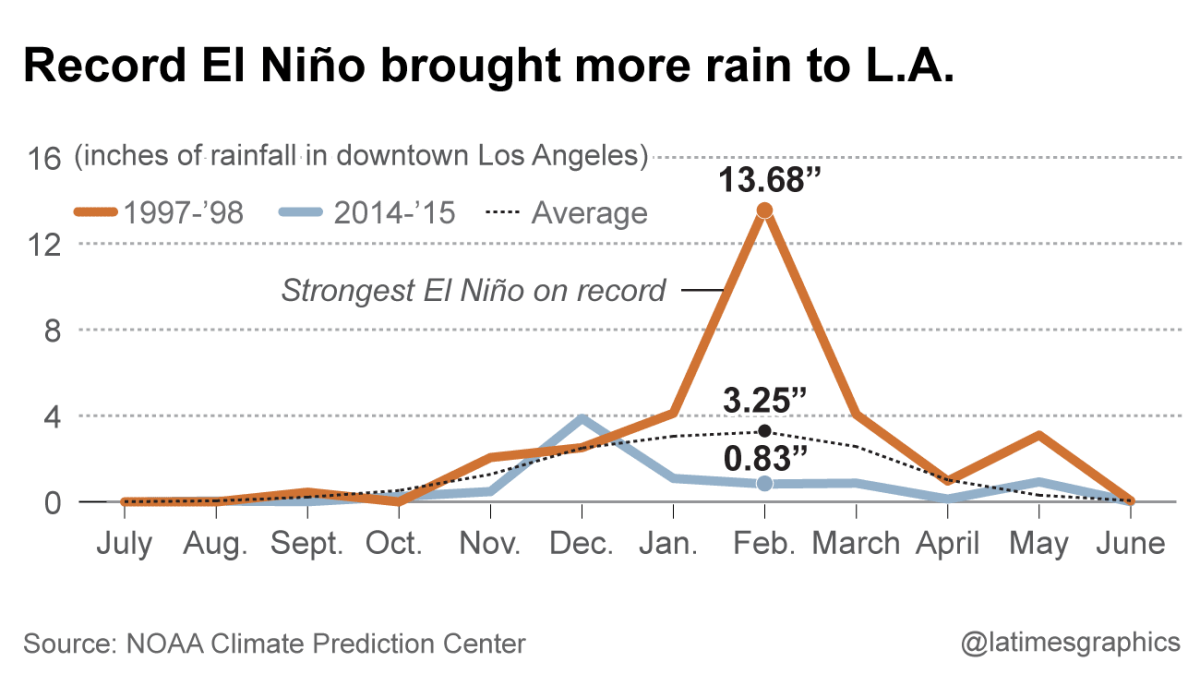

In the two biggest El Niños on record, the heaviest above-average rains in Los Angeles came during only four months – January, February, March and May, says Bill Patzert, climatologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge. Here’s what it looked like in 1997-98:

Lorena Iñiguez Elebee/Los Angeles Times

February was by far the worst. With 13.68 inches of rain that month -- almost a year’s worth of rain -- it was the wettest February since records for L.A. began being kept more than 130 years ago.

“What happens during an El Niño is that you get these larger-than-normal storms,” Patzert said. “So, after awhile, you’re getting mudslides.”

One devastating mudslide hit Laguna Beach at the end of February in 1998. Glenn Alan Flook, a lanky, athletic 25-year-old, had taken refuge in a neighbor’s home when it was struck by mud. He was thrown through a window as the room collapsed; his body was found wedged beneath a mobile home 50 yards downstream.

A mudslide had also crushed much of the home of Nicholas Allen Flores, 43. His body was found in a fetal position on a green sofa in the family room.

Water and Power is The Times' guide to the drought. Sign up to get the free newsletter >>

2. What was February 1998 like?

There were actually only a handful of storms that month, and each storm by itself was not historically big. It was the fact that they were all compressed in the space of a month.

“In that February of 1998 alone, we had four big storms and two small storms, and we got almost a year of rain in one month,” Patzert said. “So February looked like something that should’ve been spread over the entire winter.”

“Things get saturated,” Patzert said, “and the soil can’t absorb it.”

During the 1997-98 rain season, downtown L.A. got roughly double its average rainfall for the year.

3. What does El Niño mean for the rest of the United States?

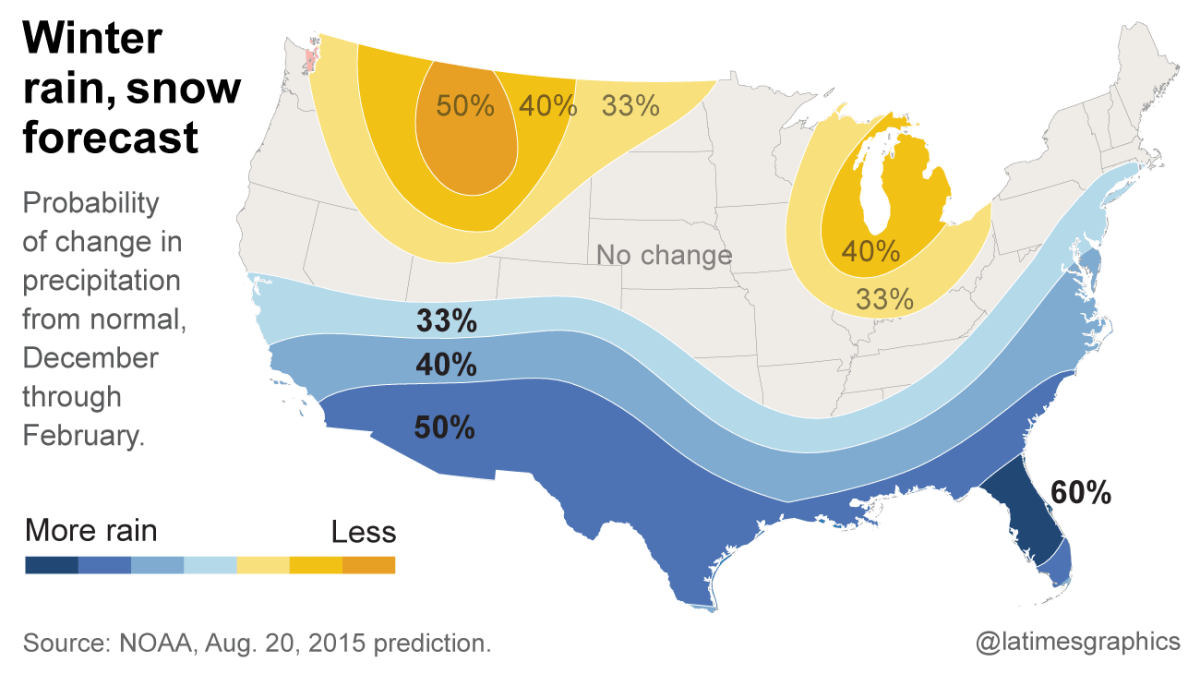

The current outlook for the winter calls for a wet south and a dry north.

Len De Groot/Los Angeles Times

It’s bad news for states like Washington, which, like California, is suffering through an intense drought. But it could mean a mild winter for Chicago and Detroit.

4. How can El Niño bring such a dramatically different winter from the last several years, which saw a parched California and relentless snow in Boston?

California’s drought has been worsened by a mass of relentless high pressure sitting atop the Gulf of Alaska, scaring off the cool, wet storms ferried by the jet stream away from the West Coast.

“It moved the jet stream into northern Canada, swooping it into the Midwest and Boston,” Patzert said. In California, “we were left high and dry, and Boston got our rain in the form of blizzards.”

The high pressure pushing on the surface of the northeastern Pacific Ocean has also caused it to heat up, forming a “blob” of warm water, which some scientists say further reinforces the drought-worsening “ridiculously resilient ridge” of high pressure.

The blob’s unusually warm waters have wreaked havoc on marine wildlife, say some experts, who blame it for thousands of seabirds and emaciated sea lion pups that have been washing ashore on California beaches. Cooler waters happen to be home to fatty, nutrition-packed plankton, the foundation of the sea’s food chain. Warmer waters bring leaner, less-nutritious plankton.

5. Will a strong El Niño be able to overcome the drought-worsening, blob-creating mass of high pressure?

Some scientists say yes.

The good news is that the weather conditions in the western Pacific tropics that are thought to have created the menacing mass of high pressure have already changed, said Mike Halpert, deputy director of the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center, to reporters last week.

Halpert says he expects El Niño to assert itself, and the ridge of high pressure to fade away.

(Officials also say that it is almost impossible for an El Niño to end California’s four-year drought in a single year. By one calculation, California’s mountainous north would need 2.5 times to three times its average precipitation to end this drought, and the record is only about double the average rain and snowfall.)

6. How does El Niño affect the path of winter storms into the United States?

In strong El Niños, the subtropical jet stream that ferries wet storms over the jungles of southern Mexico and Central America moves northward, putting a train of storms over Southern California and the southern United States, Patzert said.

The only two Godzilla El Niños on record, which hit in 1982-83 and 1997-98, were powerful enough to shift the entire jet stream to cover all of California, giving the south double its rainfall and the north double the snowpack, Patzert said. Covering the north with snow is essential, because that’s where California’s largest reservoirs are located, and they need to be fed at a gentle pace by snow melting through the spring and summer, Patzert said.

7. How is El Niño doing?

It has been at moderate strength, Halpert said, and getting stronger.

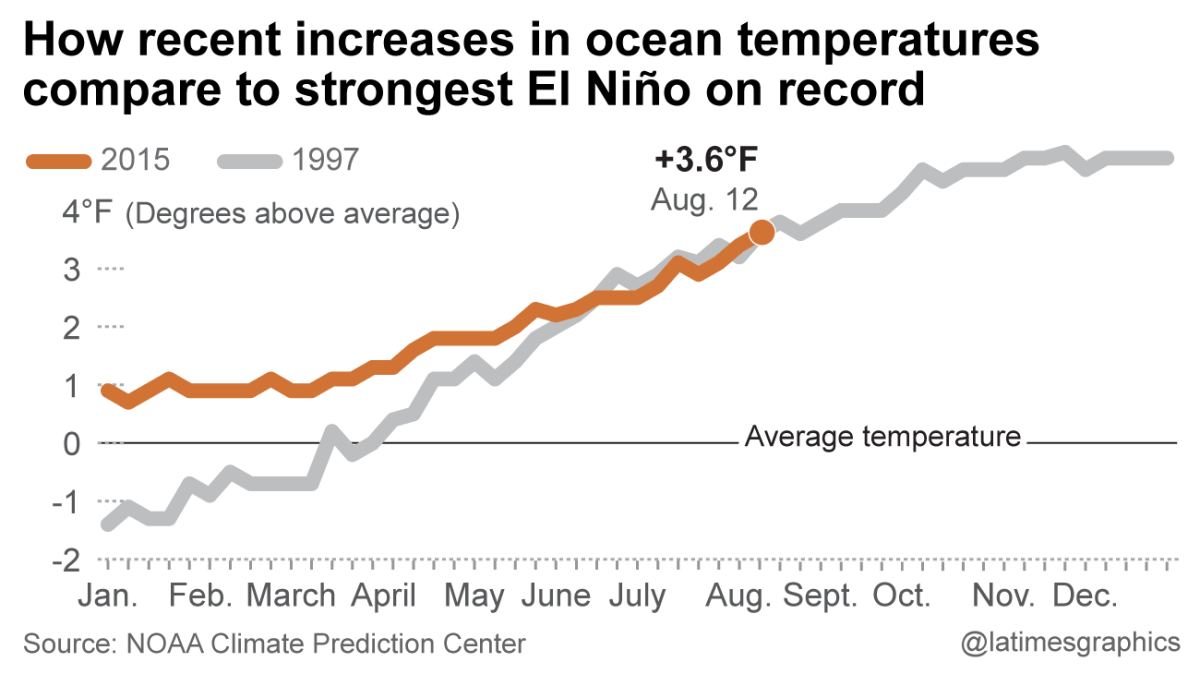

As of Aug. 12, the sea-surface temperatures at a benchmark location west of Peru were at 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit above average, the highest since this El Niño was officially declared in March.

As the following chart shows, the temperatures now are closely tracking what happened in the summer of 1997, which led up to the strongest El Niño on record.

Lorena Iñiguez Elebee/Los Angeles Times

8. Why are scientists more confident about this El Niño, when predictions in the last couple of years fizzled?

Scientists are more confident because of the remarkably warm ocean temperatures. In fact, in this benchmark location of the Pacific Ocean last month, the temperature was the highest it has ever been for the month of July since the summer of 1997.

El Niño is a weather phenomenon that involves a warming of the Pacific Ocean west of Peru. The temperature change can cause dramatic changes in weather patterns worldwide, bringing wet rains to California but drought to Indonesia and Australia.

9. Is there any risk that El Niño could sputter?

Yes. There’s one more ingredient for this El Niño to get on to steroids -- and it involves the wind.

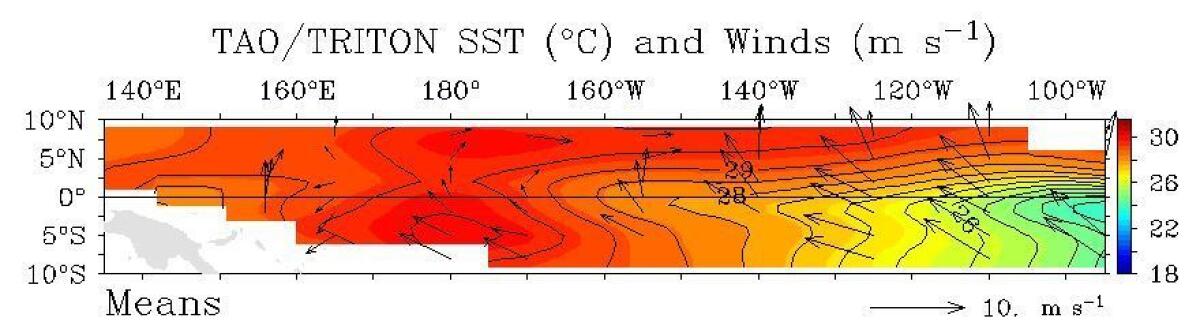

Typically, winds atop the ocean on the equator blow from east to west. These so-called trade winds allowed Spain to send its silver-laden galleons from Mexico to the Philippines. The winds are also a reason why the western tropical Pacific Ocean is so warm -- there’s time for the waters to warm up as they blow over to make the beaches of Indonesia and Malaysia so tempting.

Here’s a visual of what the trade winds are normally:

Normally, the winds at the surface of the Pacific Ocean along the equator move from east to west. This keeps the eastern Pacific Ocean cool and the west warmer.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Tropical Atmosphere Ocean Project

Note the island of New Guinea to the west, and how the winds are moving westward.

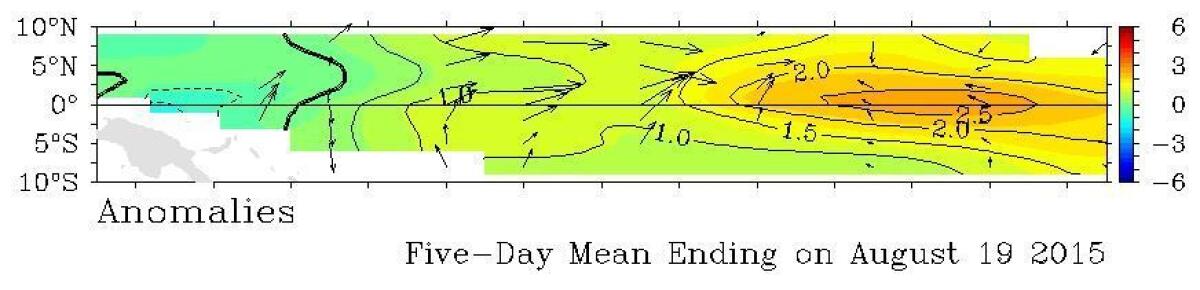

Here’s what the winds were doing this week:

The winds have dramatically weakened from their normal direction and in some cases, are moving backwards. That’s allowing warm water to pool in the eastern Pacific Ocean, which will allow El Nino to strengthen, and could mean a wetter winter than normal for California.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Tropical Atmosphere Ocean Project

They’re weakening or even reversing directions, going from west to east. That's allowing warm water to surge toward the Americas, where it needs to be for El Niño to strengthen, Patzert said.

That’s a good step, but it needs to keep happening.

"The trade winds have to continue to be weak," Patzert said, for this El Niño to grow into a Godzilla. There needs to be a sustained weakening of these winds as occurred in 1997, he said.

10. Why is the strength of this El Niño important?

Only Godzilla El Niños have been strong forecasters of heavy rainfall for California. Mediocre El Niños have a mixed track record.

“If it’s a Godzilla El Niño,” Patzert said, “it’s the best forecasting tool ever.”

“But if it’s not a Godzilla, it’s a pretty shaky forecasting tool. Because we know pretty modest El Niños can give us pretty dry winters,” Patzert said.

One of those was the moderate El Niño of 1986-87, Halpert said. The jet stream, he said, “ended up south into Mexico and they had to deal with the flooding and landslides. And California, in that particular event, was not particularly wet at all.”

While the consensus among many forecasters is that El Niño is strong and headed toward getting stronger, it's still possible something unexpected could occur. And if those trade winds don’t collapse like they did 18 years ago, Patzert said, “Godzilla could become El Gecko.”

Follow me on Twitter: @ronlinMORE ON EL NINO:

With fierce El Niño forecast, county officials look for vulnerabilities

Another El Niño sign: Ocean temps hit highest level of the year

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.