In L.A., federal grant to combat extremism stirs up concerns about targeting Muslims

Los Angeles lawmakers are wrestling with whether to accept a federal grant to counter extremism, a move that critics believe would lead to targeting Muslims.

The debate has roiled City Hall, where dozens of people turned out Tuesday to urge city officials to turn down the money. Some shouted angrily from the crowd as an aide to Mayor Eric Garcetti told lawmakers that the money would fund programs to combat Islamophobia and hatred and provide culturally appropriate services to help communities.

Los Angeles is poised to get $425,000 from the Department of Homeland Security under the Countering Violent Extremism program. Under the federal grant, L.A. would enter into contracts with local groups to foster “proactive efforts to build healthy communities,” address hate and promote youth leadership, according to a city report.

The plan alarms the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California and other groups that argue that the federal program, initiated under the Obama administration, has only become more worrisome under President Trump. ACLU staff attorney Mohammad Tajsar said it was “fundamentally flawed.”

“These programs identify individuals as potential targets of radicalism if they adhere too closely to particular strands of the Muslim faith. If they exhibit certain political ideologies. If they hang out with the wrong crowd,” Tajsar said. “All things that are protected and lawful.”

When lawmakers last vetted the proposed grant at a committee meeting in January, City Councilman Mitch O’Farrell said the fears among community members were understandable, but “I have complete confidence that accepting this grant is not tantamount to cooperating with the Trump administration in any way, shape or form.”

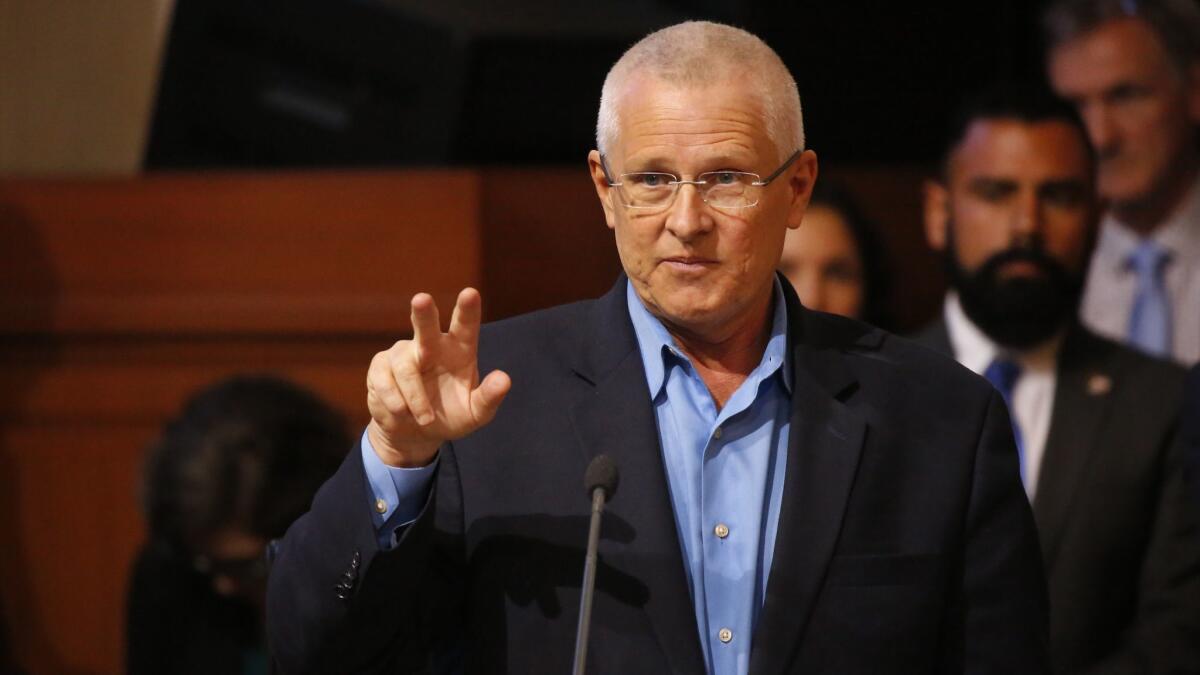

That committee recommended accepting the federal grant. But at Tuesday’s council meeting, Councilman Mike Bonin argued that although local officials had made admirable efforts to “modify” the program, the city should not be partnering with the Trump administration on terrorism because the federal government was “very clearly determined to racially profile.”

“If you lay down with dogs, you’re going to get fleas,” Bonin said. “And this is a flea-ridden program nationwide.”

After a brief back-and-forth at the council meeting, City Council President Herb Wesson asked to shunt the issue back to the committee for more discussion.

In a report issued last year, the Brennan Center for Justice concluded that the Countering Violent Extremism grants had been focused almost exclusively on American Muslim communities and that many programs “label people as potential terrorists using disproven criteria.”

“I pray five times a day. Does that mean I’m radicalized?” Ishmail Marcus Allgood of Islah L.A. asked at a January hearing at City Hall. “If I speak out on social justice issues, am I radicalized?”

Garcetti aide Joumana Silyan-Saba said that the L.A. programs would not be rooted in the radicalization theories that alarmed community activists and attorneys, but would instead focus on “protective factors,” identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, that reduce the risk that people will be attracted to violent extremism.

The federal money could pay for supportive services for individuals and families, as well as programs to encourage youth leadership, financial literacy and immigrant integration, Silyan-Saba said. She stressed that some of the funds would go to an Encino counseling center that serves a wide range of communities, including Spanish, Armenian and Farsi speakers, and some would go to a group focused on curbing the influence of white supremacists.

At the council meeting Tuesday, she told lawmakers that such programs would help battle hate and bias in all forms, including white supremacy and Islamophobia, and would operate “outside of the lanes of law enforcement.”

“Giving back this money will leave a vacuum for law enforcement solutions only,” Silyan-Saba told council members, and returning the funds would “essentially leave it open for this administration to do as they please with it.”

Some local groups, including Muslims for Progressive Values, sent in letters urging L.A. to accept the grant. But at the Tuesday meeting, only opponents spoke up.

Both critics and supporters of the federal grant have pointed to an earlier program in L.A. called Safe Spaces, a federally funded effort that included community workshops and discussions that promoted mental health, wellness and suicide prevention and explored “taboo topics” such as romantic relationships and identity, according to a report on the program. Dozens of people also got therapy or counseling.

Islamic Center of Southern California board chair Hedab Tarifi said that during that program, “there were no law enforcement involved and we were in control.”

“I trust that the mayor will not do anything harmful to the Muslim community,” Tarifi told lawmakers in January.

But critics contended that the program was nonetheless meant to target the communities it purported to serve. In a letter to the council, they complained that the final report on the pilot program reached the “unfounded conclusion” that there were symptoms that could lead to violence if they were not addressed, despite the fact that no one who had gotten counseling had made any threat of public violence.

Garcetti aides said that under the program, the city would not collect any personal identifying information or require groups that get money to turn it over to them. Lawmakers have suggested requiring a quarterly report on where and how the money is being used, as well as what information is being collected and who has access to it.

Laboni Hoq, litigation director for Asian Americans Advancing Justice — L.A., called that “cold comfort.” She argued that even if community groups do not have to turn over information to the city, they could still end up collecting information that could ultimately fall into the hands of the federal government.

Her group joined with the ACLU, the Council on American-Islamic Relations and the grassroots Vigilant Love coalition to sue the city last week, alleging that the mayor’s office, the Los Angeles Police Department and a city commission had failed to fully answer requests for public records on the grant. Attorneys said they wanted to get those records to arm residents with information before they decided whether to participate in programs.

Garcetti spokesman Alex Comisar declined to comment on the lawsuit Tuesday.

Twitter: @AlpertReyes

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.