Earthquake on the beach: Scientists think a 7.4 temblor could reach from L.A. to San Diego

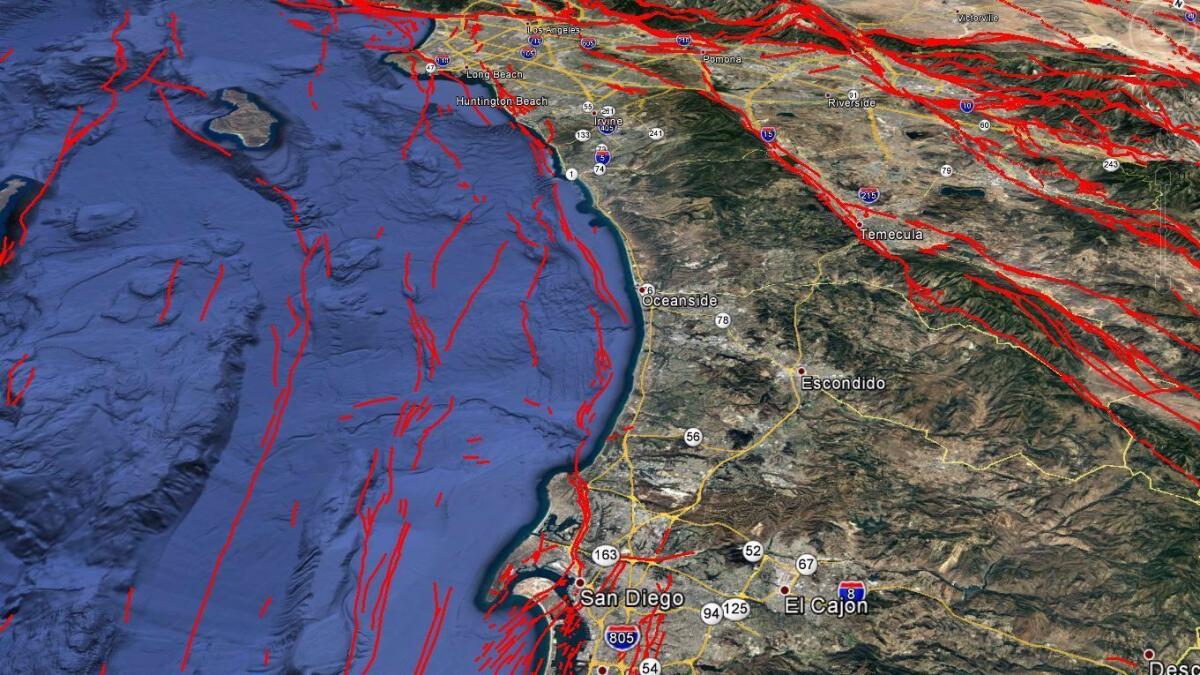

The discovery of missing links between earthquake faults shows how a magnitude 7.4 temblor could rupture virtually simultaneously underneath Los Angeles, Orange and San Diego counties, a new study finds.

Such an earthquake would be 30 times more powerful than the magnitude 6.4 Long Beach quake in 1933, which killed 120 people.

But to get to a 7.4, the earthquake would not only have to again rupture the Newport-Inglewood fault in Los Angeles and Orange counties. It would also have to jolt the adjacent Rose Canyon fault system, which runs all the way through downtown San Diego and hasn’t ruptured since roughly 1650.

“These two fault zones are actually one continuous fault zone,” said Valerie Sahakian, the study’s lead author, who wrote it while working on her doctorate at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego. Sahakian is now a research geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

In the past, scientists reported gaps between the two fault systems of as much as 3 miles apart. But the latest study shows the gaps are actually less than 1¼ miles apart.

“That kind of characterizes it as one continuous fault zone, as opposed to two different, distinct fault systems,” Sahakian said, making it far easier for an earthquake to keep shaking land as it races down a longer fault, widening the seismic reach of the temblor.

There had already been consensus among scientists over the last three decades that the fault systems were actually one, said Caltech seismologist Egill Hauksson, who was not involved with this study. “We now have real evidence that this is the case,” Hauksson said.

The difficulty in proving it was caused by the location of the gap — under the Pacific Ocean between Newport Beach and La Jolla. Drawing a better map meant trying to figure out where the fault was underwater.

So Scripps researchers hopped aboard boats, and in the fall of 2013 spent more than 100 days at sea collecting data. They created an image of what the earth looks like under the seafloor to estimate where the fault lies.

To do so, they used a technique kind of similar to how submarines use sonar or bats use echoes to see.

From the ship, scientists towed a machine that generates acoustic waves that bounce off the seafloor and deeper underground layers and returns to the ship, giving the data the scientists need to produce a better map of where the faults actually are located. The researchers also used previously collected data to perfect their new map.

The study was published online Tuesday in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

Work on this fault is a reminder that major earthquakes can strike Orange and San Diego counties, regions that have not undergone catastrophic seismic damage in recent generations.

Orange County, for instance, is sandwiched between the Newport-Inglewood and Whittier faults, Hauksson said. Also underlying the region are the Elsinore fault and Puente Hills thrust fault.

And there’s the problem of the fault being located along the shoreline, Hauksson said, “which can have a soft, water-saturated soil.

“So you would see a lot of liquefaction in the coastal areas, which means there will be a lot of damage to all kinds of coastal structures or piers,” Hauksson said.

In such a quake, hard-hit areas might need to reach out as far as the Inland Empire and Ventura and Santa Barbara counties for help.

There is one possible bright spot for the beaches. The chance of a major temblor in our lifetime on the Newport-Inglewood/Rose Canyon fault is less than a temblor on the southern San Andreas fault, which runs further inland through mountains, valleys and desert.

That’s because the land on either side of the southern San Andreas is moving fast, pushing against the other at a rate of more than 1 inch a year. The fault is accumulating energy that will be suddenly released in a major earthquake some day.

In contrast, the Newport-Inglewood/Rose Canyon fault is moving far more slowly. At its north end, the fault is moving one-hundredth of an inch annually.

“These faults are moving pretty slowly compared to the San Andreas, so the likelihood is pretty small — but it’s still there,” Hauksson said. “It’s almost like a lottery ticket. If you buy a ticket, you have some chance of winning, but it’s exceedingly small.”

While San Diego County may be spared the worst from a San Andreas earthquake, Orange County could be hit hard from either the coastal fault or the San Andreas, which is expected to send powerful seismic waves into the Los Angeles Basin, whose soft soils exacerbate shaking like Jell-O.

“They’re on the same soft sediment as the city of Los Angeles,” Hauksson said of Orange County.

The funding for the fault research came from Southern California Edison, the operator of the San Onofre nuclear power plant located on the north tip of the San Diego County coast. The nuclear plant stopped producing electricity in 2012 and is being decommissioned.

Two years earlier, the California Energy Commission directed Edison to evaluate earthquake faults that could affect the power plant. One result of the research was finding that the seismic risk to San Onofre was less than previously feared, with experts concluding that a hypothetical Oceanside blind thrust fault did not actually exist, according to Edison spokeswoman Maureen Brown.

The other finding — the proof that the Newport-Inglewood and Rose Canyon faults connect — does not change the risk assessment for the power plant, where radioactive nuclear waste is stored.

Buildings that house the nuclear waste are expected to withstand ground shaking from a hypothetical magnitude 7.5 earthquake, larger than what the coastal fault is capable of producing, according to Brown.

Edison decided to decommission the plant after a small amount of radiation leaked in one of two steam generators that had been recently replaced. The generators convert water to steam from heat produced through the nuclear reaction. The steam powers a turbine that creates electricity.

The nuclear power plant’s closure was not related to the earthquake study, Brown said.

The northern end of the Newport-Inglewood/Rose Canyon fault zone is near the northwestern border of Beverly Hills and the Westside of Los Angeles.

Among the cities that the fault cuts through are Inglewood, Carson, Long Beach, Signal Hill, Seal Beach, Huntington Beach, Fountain Valley, Costa Mesa and Newport Beach. At that point, the fault goes under the ocean and parallels the coast of Orange and San Diego counties. The fault resumes its path under dry land through the La Jolla neighborhood of San Diego, and continues through downtown and Coronado.

Besides Sahakian, the study’s other authors are Neal Driscoll and Alistair Harding of Scripps, as well as Jayne Bormann, Graham Kent, and Steve Wesnousky, who were affiliated with the Nevada Seismological Laboratory at University of Nevada, Reno while conducting the study.

ALSO

A section of the San Andreas fault close to L.A. could be overdue for a major earthquake

Preliminary quake map shows fault lines under schools, hotels, homes

Get ready for a major earthquake. What to do before — and during — a big one

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.