DNA identifies suspect in 1986 killing of Agoura Hills boy

Miguel Antero hopped off the school bus on a spring day in 1986 but he never came home.

His body -- covered in stab wounds -- was found hours later amid brush near an Agoura Hills commune where he lived.

Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies scoured the scene along Triunfo Canyon Road for clues, but the case grew cold until March of this year.

One of the original detectives on the case, retired sheriff’s Sgt. John Laurie, was watching the news at his Orange County home when he spotted a likely suspect.

On television, Laurie saw that Pomona police had arrested 53-year-old Kenneth Rasmuson in Idaho in connection with the 1981 killing of a 6-year-old boy who was kidnapped from his Anaheim Hills home.

“I said, ‘That’s our suspect.’ I obviously recognized him,” Laurie recounted Thursday.

He called the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department’s cold case unit and asked a trusted investigator to gather up all the evidence from Miguel’s killing.

“Take it to the lab and just run it through. I’m convinced this is our suspect,” Laurie recalled.

After extensive DNA analysis established a match, the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office filed a murder charge Thursday against Rasmuson, alleging he killed the first-grader while performing a lewd or lascivious act, according to the complaint.

Rasmuson is scheduled to be arraigned Wednesday in Pomona. Prosecutors have not yet decided whether to seek the death penalty.

Laurie said he had long suspected that Rasmuson had killed Miguel.

Exactly one year after Miguel’s death, on April 8, 1987, Rasmuson abducted a 3-year-old boy from a home west of downtown Los Angeles and sexually abused the child before abandoning him in a remote area along Kanan Road in the Agoura area, authorities said. The boy was found naked by a passerby.

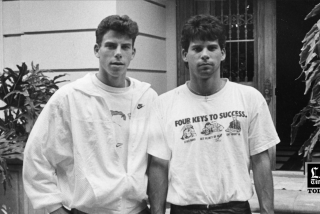

Days after the sexual assault, Rasmuson, then 25, was flanked by his parents when he walked into the LAPD’s Rampart station and surrendered. He pleaded guilty to kidnapping and molestation charges. A judge sentenced him to the statutory maximum of 17 years in prison after a prosecutor called Rasmuson “an unrepentant child molester.”

The timing of the abduction, right down to the day, drew Laurie’s attention.

Along with his partner at the time, Det. Jack Fueglein, he obtained a search warrant to canvass Rasmuson’s Santa Barbara residence and secured a jailhouse interview.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

But Rasmuson invoked his right to an attorney, effectively ending the interview. The search of his home unearthed evidence, but not enough to make a case, he said.

“There were never any other suspects,” Laurie said, “but we did not have enough to proceed.”

Rasmuson was arrested March 27 at the home he shared with his parents in Sandpoint, a resort town in the Idaho panhandle.

According to Pomona detectives, DNA connected him with the 1981 strangling death of Jeffrey Vargo, who vanished from Orange County and was found dead at a Pomona construction site.

Rasmuson had been living quietly in Idaho for about five years, although his arrival there triggered protest because of his criminal history.

He was committed in 1982 to Atascadero State Hospital in Central California after being declared a mentally disordered sex offender for sodomizing and orally copulating an 11-year-old Santa Barbara boy. He was released after two years.

After completing his prison sentence in connection with the 1987 abduction, Rasmuson spent time in Santa Barbara County, Oregon and Washington before going in Idaho.

For the investigators, other cases came and careers carried on. Fueglein died in 1995, and in 2003, Laurie retired from the department.

For Miguel’s family, the unsolved killing was like a festering, untreatable wound -- a sharp contrast from life before April 8, 1986.

“Things were looking good,” Shankara Antero recalled Thursday of the time leading up to his son’s death. He said he and his wife had just moved from Colorado to California “on the notion that the grass was green.”

His family created a home at the Vedantic Center, a commune of about a dozen families founded by Alice Coltrane, widow of jazz musician John Coltrane. There, Eastern philosophy coupled with Buddhist, Islamic and Christian texts to imbue spirituality into everyday life.

That serene, bucolic life vanished when Miguel failed to come home from school.

“The trap door fell from under me,” Antero said. He and his wife later divorced, and he bounced around, living in Florida and Colorado. For more than a year, he said, he was homeless. News of the DNA link to a suspect in his son’s killing brought a measure of relief, he said.

Miguel’s mother, Ana Bradshaw, said she never lost hope that her son’s killer would be found. Each year, she called the sheriff’s department, telling detectives, “I’m a taxpayer. Do not close that case. We need to get that monster off the streets.”

When sheriff’s Det. Joe Purcell called her Thursday to inform her of the charges against Rasmuson, she thought he was playing a cruel hoax. After the news set in, the strain of an agonizing, 29-year-long wait gave way.

“I just broke down in tears,” Bradshaw said from her Fayetteville, Ga., home. “It took a long way into the middle of the night just to stop sobbing.”

In the aftermath of her son’s death, she said, she fell into a hole – moving from place to place, burdened by grief. She credits her daughter Enid, who was 11 at the time of Miguel’s death, with pulling her out, along with her new husband, who had two sons of his own. Now, she has five grandchildren.

At Rasmuson’s next court appearance, Bradshaw said she plans to sit in the courtroom.

“I want to see that person, eye-to-eye,” she said. “I want that person to look into my eyes. I don’t want to say anything to him. I want to know if he has something to say to me.”

For breaking news in California, follow @MattHjourno.

ALSO:

L.A. coroner investigating case of stolen leg

Man who was beaten by San Bernardino deputies arrested (again) on assault charge

British court blocks extradition of sex-abuse suspect, saying California law violates human rights

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.