Could Venice be cut out of L.A.’s new rules on Airbnb-type rentals?

In the enduring battle over Airbnb and similar rentals in Los Angeles, perhaps no turf has been more hotly contested than Venice.

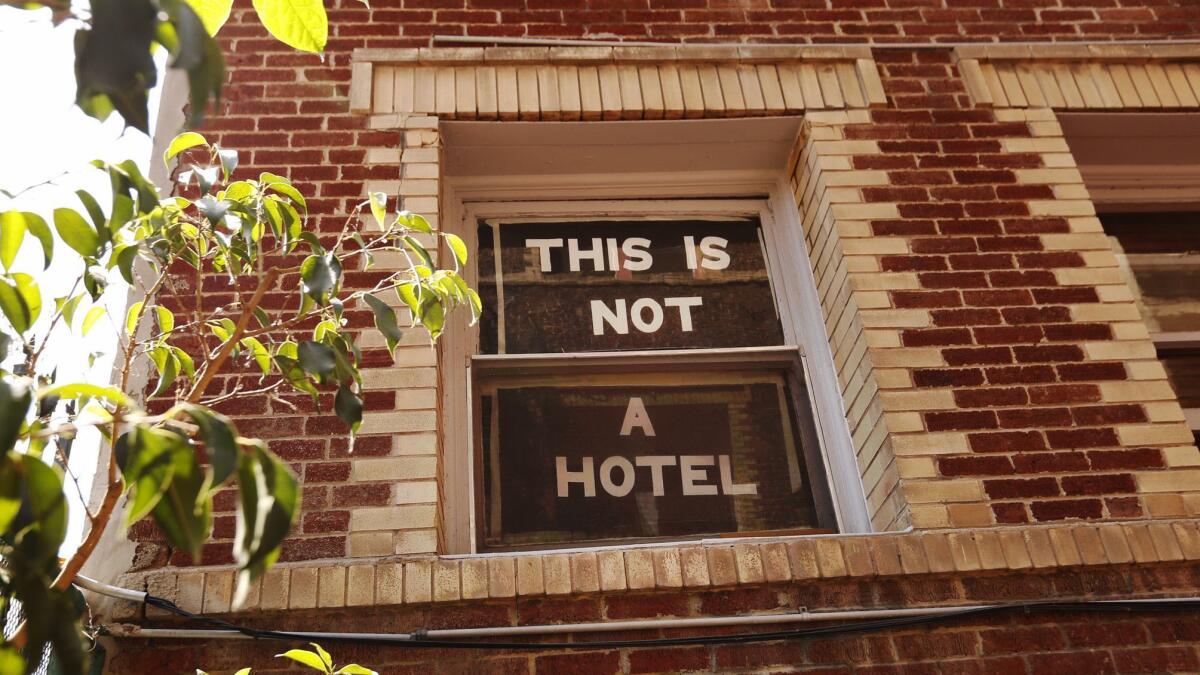

Tenant activists complain that apartment buildings here have mutated into beachside hotels for a revolving door of tourists, who flock to this bohemian stretch of the California coastline and its eclectic boardwalk.

The losers, they say, are longtime renters pressured out of their homes to make way for travelers paying steeper rates.

Now a new law is supposed to put a stop to what City Councilman Mike Bonin dubbed “rogue hotels.”

But critics argue that it cannot be enforced in Venice and other coastal parts of Los Angeles. And they plan to go to court to stop it.

L.A.’s rules, which go into effect in July, allow Angelenos to rent out only their own primary residence for short stays, barring them from offering up a second home or investment property to travelers.

The rules are intended to prevent apartment buildings from being bought up and run like hotels, exacerbating the housing crisis.

Critics have argued that the new rules will eliminate lodging options for families and other vacationers who do not want to go to a hotel, dealing an economic blow to neighborhoods.

As July draws near, some charge that the city has failed to properly vet its plans with the California Coastal Commission, which regulates coastal areas across the state.

Two and a half years ago, the commission chair warned cities that although it supported “reasonable and balanced regulations” on short-term rentals, banning such rentals entirely in coastal areas could violate the Coastal Act. The concern was that an outright ban could put beach vacations out of financial reach for many Californians.

The Coastal Commission urged cities to make sure that such regulations were either incorporated in a comprehensive plan called a Local Coastal Program — which L.A. is still working on — or authorized with a coastal development permit.

Attorney Thomas Nitti, who represents building owners, said L.A. did not appear to have done that.

“It seemed that no one at the city considered that they had to collaborate with the Coastal Commission,” said Nitti, who said he is preparing a lawsuit for several rental operators.

“It’s a very serious issue,” he said. “The city is putting an obstacle in the way of low- and moderate-income people who would like to stay in the coastal zone.”

In reaction to questions about the issue, Coastal Commission spokeswoman Noaki Schwartz said commission staffers do not believe that the L.A. rules are legally enforceable in the coastal zone without some kind of authorization under the Coastal Act, which the city has yet to obtain.

However, commission executive director Jack Ainsworth added that “our intent is not to punish our local government partners as they grapple with the challenging issues and competing interests” surrounding such regulations.

Ainsworth said that commission staffers had been working with L.A. to incorporate its rental rules into a Venice Local Coastal Program that is being developed.

Los Angeles officials, in turn, said that the city was on track to start implementing the ordinance citywide in July.

“We are working closely with Coastal Commission staff to memorialize our home-sharing regulations through the ongoing [Local Coastal Program] process,” planning department spokeswoman Agnes Sibal-von Debschitz said in a statement. “In the meantime, we believe we will be able to implement the ordinance as planned.”

L.A. officials pointed to a court battle over Hermosa Beach, which banned renting out homes for short stays in residential zones.

Rental operators went to court to block the rules, arguing they were preempted by the Coastal Act, but an appellate court concluded last year that the Hermosa Beach law “did not fall under the auspices of the Coastal Commission.”

But in Santa Barbara, similar rental restrictions were halted along the coast after Theo Kracke, whose business manages vacation rental properties, challenged them in court.

In his decision, a Superior Court judge found that unless Santa Barbara got a coastal development permit or a certified amendment to its coastal plan to authorize the restrictions, the city was not operating in line with the Coastal Act when it took action to “nearly eliminate” such rentals from the coastal zone.

Santa Barbara City Atty. Ariel Calonne said the city strongly disagrees with the decision, arguing that the city merely stepped up enforcement of a long-standing rule, but has not yet decided whether to appeal. It plans to update its Local Coastal Program to regulate such rentals in coastal areas.

Robin Rudisill, a Venice resident who ran unsuccessfully against Bonin for City Council, said she had raised the issue with Coastal Commission staffers, asking them to talk to L.A. city officials and make sure the new rules could go into effect along the coast.

The issue worries Keep Neighborhoods First co-founder Judith Goldman, whose group advocated for tighter regulations on short-term rentals.

“Let’s hope the city has a plan and that this isn’t an oversight that’s coming up at the 11th hour,” Goldman said.

The legal dilemma could have big implications for tenants and rental operators in Venice, one of the hottest spots for short-term rentals in L.A.

At the Ellison, a brick building steps from the beach, Brian Averill and other tenants have accused their landlord of trying to pressure them out with an ongoing stream of travelers renting rooms for a few nights, neglected repairs, and noisy shows in the courtyard.

Bonin has denounced the Ellison as the “poster child” for the problem the city is trying to solve.

The company that owns the Ellison, Lance Jay Robbins Paloma Partnership, has denied such claims and argues the Venice building had been wrongly categorized decades ago by the city as an apartment house.

The firm argued that the building had a vested right, based on its historic use, to be rented out for short stays.

At a hearing last month, the West Los Angeles Area Planning Commission rejected those arguments.

But the building owner, who is represented by Nitti, has since sued the city over that decision — the latest step in a long battle over the Ellison. Fewer than a dozen tenants remain at the rent-stabilized building, which is advertised online as the “Ellison Suites.”

If L.A. cannot enforce the new rules in Venice, “it would be heartbreaking,” Averill said. “It’s like getting the rug yanked out from under us.”

L.A.’s soon-to-be-effective rules impose several restrictions on renting out homes for short stays. In addition to limiting hosts to renting out their own primary residence, the regulations prohibit such night-to-night rentals in apartments covered by the Rent Stabilization Ordinance.

They also cap the number of nights that homes can be rented out to travelers annually, although Angelenos can exceed that cap if they meet specific requirements.

“We crafted these regulations to allow people to rent an extra room to help make ends meet, while still putting in place smart and enforceable rules that protect neighborhoods, and keep affordable housing from becoming exclusive short-term rentals,” Bonin said in a statement, adding that his understanding is that the planning department is “working to ensure” that the new rules go into effect citywide in July as planned.

Philip Minardi, director of policy communications for the vacation rental company HomeAway, argued that although L.A.’s ordinance was not an outright ban, barring people from renting out a second home or investment property for short stays would nonetheless raise a “red flag” for the Coastal Commission.

“The reality is that you’re banning a huge swath of this industry, particularly in those coastal zones,” Minardi said.

Twitter: @AlpertReyes

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.