The Clampers: A historical drinking society or a drinking historical society?

Everyone had forgotten about the Butt Lake Dinky by the time workers in 1996 dredged up the rusty H.K. Porter steam locomotive that had been submerged in a reservoir for eight decades.

That lack of remembrance didn’t sit right with the Order of E Clampus Vitus, a men’s fraternal organization with chapters scattered around Gold Country. They commemorated the teeny train with a bronze plaque.

From his perch at the Plumas Club, a dive bar that serves as his chapter’s de facto headquarters, Ron “Right-On” Oxley swirled a vodka and cranberry juice and tried to sum up his often misunderstood group.

“A lot of people get confused and think we’re a bunch of drunkards,” said the resident of Quincy, a small mining town. “We’re actually a nonprofit historical organization.”

America is full of memorials for epic battles and soaring monuments and somber cradles of famous historical figures. The men of E Clampus Vitus — a.k.a. the Clampers — don’t bother with those.

“We believe in the absurd,” said Gene Koen, a Clamper from Oroville.

In Truckee, the group paid homage to the Tin Can bar from the early 1900s and Dot’s Place, a brothel. In Mono County, a Clampers plaque honors the Legend of June Lake Slot Machines: illegal machines said to have been tossed in the lake in the 1940s and sought by cold-water divers.

In a kind of running theme, the Clampers seem to celebrate a fair number of places overtaken, biblical-like, by water.

The group once paid tribute to the town of Prattville, whose original buildings are submerged beneath Lake Almanor. A bunch of Clampers in 1973 got a boat and chucked a plaque into the water.

The Clampers, according to the Frank C. Reilly Chapter of Northern California, have plaqued hundreds of places, “from ghost towns to saloons, from bordellos to ranchos, from heroes to madmen.”

According to Clampers lore, their first California lodge was established in Mokelumne Hill in 1851.

The group parodied the sashes and ceremonies of stuffier and wealthier social clubs, like the Odd Fellows and Freemasons. Clampers wore red shirts symbolizing miners’ long-john underwear and cut pieces of tin cans to pin to their vests.

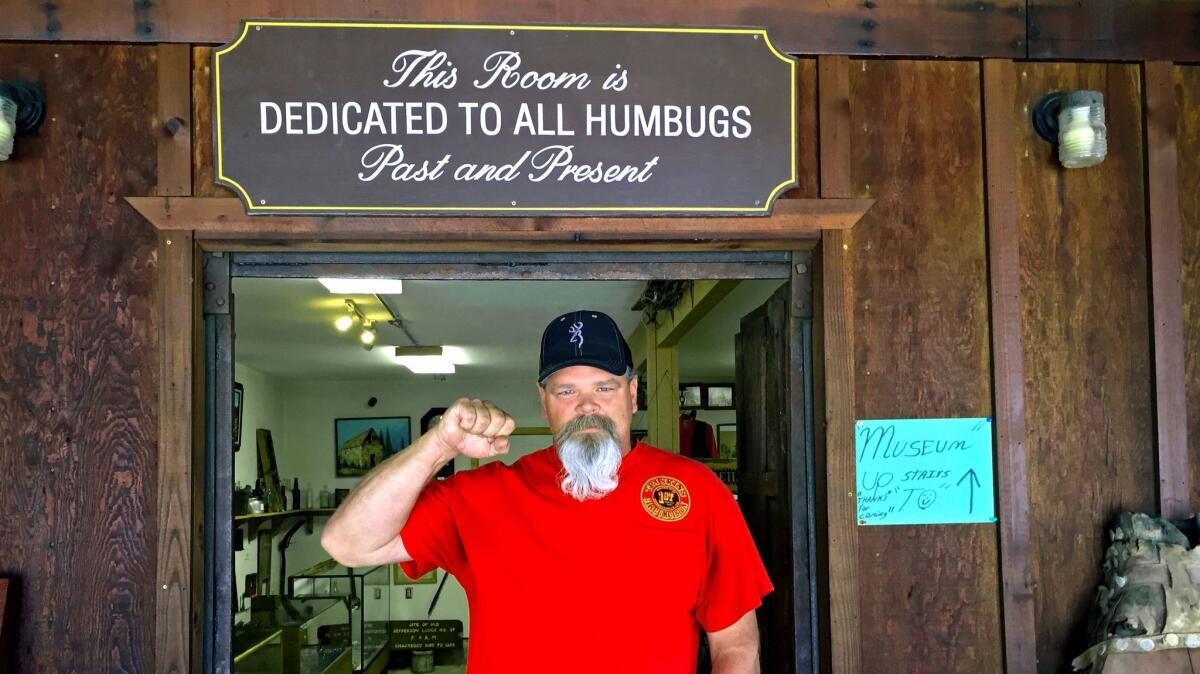

Chapter presidents hold the ceremonial title of Noble Grand Humbug. The sergeant-at-arms is the Damfool Doorkeeper. They’re secretive about initiation rites.

What, exactly, does “E Clampus Vitus” mean? No one knows. Their motto is Credo Quia Absurdum, which, in Latin, roughly translates to “I believe because it’s absurd.”

The organization today claims 45 chapters in eight Western states and thousands of members. Enter a bar in a small town in the Sierra Nevada, and you’re likely to run into a Clamper.

“The Clampers really like to promote the drunken historian persona … but when it comes down to history, they are pretty serious, even though they might not pick the most conventional places,” said Nicole Grady, a librarian at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, which holds an extensive Clampers archive.

The group is not well-known outside California. Grady said she’d never heard of them until she started working with their archives. Now she gets excited when she spots an ECV bumper sticker or plaque.

Perhaps nowhere are the Clampers more revered than in the Sierra Nevada, where they flourished in the small towns and prospector camps during the Gold Rush.

Drive through the remote Northern Sierra town of La Porte — population 26 — and it’s hard to miss the Clampers’ presence. On serpentine Main Street, with mining equipment from 1911 sitting out front, sits the Frank C. Reilly Museum, a two-story Clampers repository named after a local saloon owner who was Chapter 5978’s first Humbug.

The museum boasts a treasure-trove of Clampers relics, Gold Rush artifacts and antiques from the area’s once-large Chinese population. There’s also the “World’s Largest Butter Dish Collection,” an assortment of ornate dishes with delicate painted flowers, glass cherries and fragile flourishes.

On a recent Sunday, Gene “Chainsaw” Koen, an appliance repairman with a bushy white goatee, kept watch over the collections. Koen has been a Clamper for 17 years and has served as the Chapter 5978 Humbug. When it’s quiet at the museum, he spends the afternoons reading up on local history.

Asked how he got the name Chainsaw, he explained that a fellow Clamper years ago somehow got it in his head that Koen had cut off his own kneecap with a chainsaw. He lifted the leg of his jean shorts and shrugged as he revealed the absence of any scar to support the story — and Koen’s nickname.

For him, it was the charity work of E Clampus Vitus that drew him in. In La Porte, the Clampers often clean up, and put up a fence around, the pine cone-strewn cemetery, where wooden and marble headstones date to the 19th century and where Frank C. Reilly is buried.

Koen said the group has long been known for helping “widders and orphans,” a phrase dating to the Gold Rush era. Back in the day, if a miner got killed and left behind a wife and children, Clampers made sure they were well cared for, he said.

“We don’t put up with no hittin’ on women or beatin' on kids,” Koen asserted.

Clampers signage is all over La Porte, the site of what’s believed to be the Western Hemisphere’s first organized downhill snow skiing tournament in 1867. A miner named Cornish Bob was victorious.

The Clampers paid tribute to the area’s skiing history and the Alturas Snowshoe Club that organized the tournament with a monument that read, “Dope is King!” — a reference to the homemade wax that skiers applied to their 12-foot-long wooden skis.

About 30 miles north, in the town of Quincy, is the Plumas Club, with a neon ECV sign in the window. A plaque says the bar was built in 1914 and operated as a dairy store with slot machines during Prohibition.

“Ancient photos indicate that ECV No. 8 has made this their ‘offishul’ waterin’ hole,” it reads.

On a recent afternoon, Garth Brooks’ “Friends in Low Places” played over the speakers, and a few Clampers sat around the well-worn wooden bar.

“Big” Bruce Robbins, a county worker and three-time Humbug from Quincy, said most people around here feel comfortable hanging around bars. As a boy, he said, he’d take a school bus from near a bar, and after school, that’s where everyone seemed to be.

Robbins, who does not drink, clutched a Pepsi.

Oxley, a fellow member of the Las Plumas Del Oro Chapter, sat by the bar’s memorabilia-filled corkboard called the Wall of Comparative Humbugery.

A construction worker originally from Muskogee, Okla., Oxley said he didn’t know anything about Gold Rush history until he joined the Clampers in 2010. Now, he can’t stop reading about it.

Across the bar, someone heard them talking about the group and hollered.

“Buncha drunkards!”

Twitter: @haileybranson

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.