L.A. is hemorrhaging bus riders — worsening traffic and hurting climate goals

To be on time for her 9 a.m. class at Cal State Northridge, Yurithza Esparza has learned the hard way that she needs to be at the bus stop no later than 6 a.m.

She would prefer to drive the 30 miles from her home in Boyle Heights, but the car she saved to buy was totaled when another driver ran a red light. So she is back on public transit, taking three buses and a train to get to school.

“Driving here is a pain because of the traffic, but it’s still more convenient,” said Esparza, 23, who can spend five hours a day commuting. “On the bus, I just can’t get from Point A to Point B whenever I need to go. I hate it.”

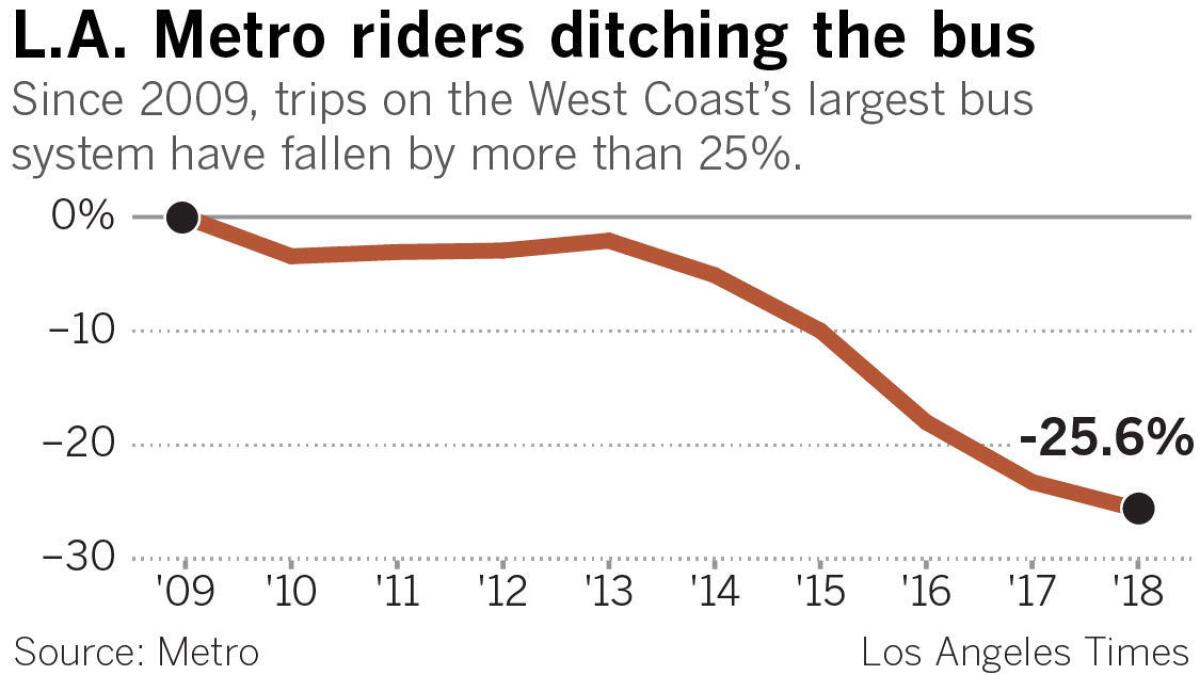

Over the last decade, both Los Angeles County’s sprawling Metro system and smaller lines have hemorrhaged bus riders as passengers have fled for more convenient options — mostly, driving.

Southern Californians are capitalizing on a stronger economy by buying cars in record numbers, experts say. They also point to half a dozen other factors putting pressure on bus systems, including falling immigration rates, rising rents that have pushed low-income families to more remote areas, and a law that allows immigrants in the country illegally to apply for driver’s licenses.

Dropping ridership follows years of complaints about bus routes that are rarely as fast or reliable as driving and often require long waits, multiple transfers and delays in rush-hour traffic. More recently, a surge in the region’s homeless population has sparked concerns about safety and sanitation.

Ridership has fallen on almost all local bus systems, including routes in Santa Monica, the San Gabriel Valley, the Antelope Valley and Orange County, mirroring a national slump in bus ridership.

Metropolitan Transportation Authority buses, which carry most of the county’s bus riders, have lost nearly 95 million trips over a decade, according to federal data. The 25% drop is the steepest among the busiest transit systems in the United States and accounted for the majority of California’s transit ridership decline.

The bus exodus poses a serious threat to California’s ambitious climate and transportation goals. Reducing traffic congestion and greenhouse gas emissions will be next to impossible, experts say, unless more people start taking public transit.

Now, transportation officials and advocates are puzzling over how to transform the humble bus into something more than a last resort.

That will require attracting some of the 14 million Southern California residents who rarely, if ever, set foot on a bus or train. Fewer than 3% of residents take more than 25% of the region’s transit trips. The vast majority of riders are Latino or black, studies show, with no access to a car and little time to lobby for better service.

“We have neglected buses in Los Angeles for a long time,” said Jessica Meaney, the executive director of the nonprofit organization Investing in Place. “We’ve lived with subpar service for so long that it’s hard for people to rally around improving it.”

Improving Metro’s market share

To reverse the slump, Metro is preparing to redesign its network of 165 lines and 14,000 stops for the first time in a generation. A study launched two years ago is examining where people go and what can be done to make the bus more competitive with driving.

The analysis is based on data from 5 million phones, tablets and other devices showing where residents, tourists and business travelers go and whether the bus or train can get them there. In the vast majority of cases, Metro could, said Conan Cheung, a senior executive officer overseeing the study.

How long it would take is another question. When taking the train or bus was as fast or faster than driving, people took transit 13% of the time. Metro’s market share falls off sharply from there.

“Having a good basic service is critical, and that service has to be run well,” Cheung said. “If it’s not on time, if we don’t have priority, or if we can’t speed up our service in relation to driving, then it’s going to be difficult to capture new riders.”

It will also be difficult to keep current ones. Last year, UCLA researchers found that Southern California families have scrimped and saved to put even modest pay increases toward cars, aided by the rise of low- and zero-interest auto loans. From 2000 to 2015, the share of households that had no access to a car fell 30%. In immigrant households, it fell 42%.

Soon, that will include Maria Sanchez, 52, who rides the Metro Line 16 bus to reach the homes she cleans in Beverly Grove.

When her family lived in Westlake, her commute was easier. Rising rents pushed them to El Monte. Now, she spends more than three hours a day on the bus.

“Every day is long,” Sanchez said, as the bus crawled down 3rd Street in rush-hour traffic. She was recently hired to clean another home, she said, and she and her husband are saving the extra income for a car.

Experts have urged Metro to focus on improving a dozen workhorse bus lines that have accounted for more than one-third of its ridership losses this decade. Those lines have shed nearly 30 million trips along major corridors, including Sunset and Wilshire boulevards, and Western and Vermont avenues.

Trips on the Line 66 bus, which Esparza rides from Boyle Heights to downtown on the first leg of her journey to CSUN, have fallen by half. Some passengers have shifted to the Gold Line, which opened to Boyle Heights in 2009. Others have left transit altogether.

Erick Huerta got around L.A. for three decades on the bus and his bicycle. When he took a job at a nonprofit in South L.A. four years ago, he tried for months to find a reliable, predictable way to get from Boyle Heights without driving — but often wound up waiting for half an hour or more in the sun, or arriving at work sweaty and late.

He and his girlfriend eventually pooled their money and bought a used Saturn SUV from a friend. The purchase, he said, “has been completely worth it.”

“Metro has this laser focus on getting people who grew up with cars, or who are regular drivers, to take public transportation,” Huerta said. “They should start with continually supporting the folks who rely on it.”

Buses sit in traffic, and traffic is getting worse

The average speed of a Metro bus has dropped 12.5% over the last 25 years, according to data analyzed by UCLA. The delays are worse on major corridors, including Vermont, which has at least 10 hours of severe congestion per day and an average local bus speed of 9 mph.

The only lasting solution, advocates say, is to carve out space for buses on major streets using bus-only lanes and bus rapid transit.

Bus rapid transit — such as the Orange Line in the Valley — works much like rail, with platforms, dedicated right-of-way and frequent service. But it costs far less to build. Revenue from Measure M, the sales tax increase voters approved in 2016, is funding four of the projects over the next 40 years, including on Vermont.

A bus lane is just paint on the street, but can still achieve major speed improvements. A temporary 1.8-mile bus lane on Flower Street in downtown, put in place during closures on the Blue and Expo lines, is expected to save riders 7 to 9 minutes per trip, Metro officials said.

“You can see the bus zoom by traffic,” Meaney said. “That really resonates with people. Whatever you give priority to, people will pick that.”

Bus lanes come at a cost for drivers: a loss of parking, a loss of driving space, or both. Earlier this year, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti joked that bus lanes are only “slightly less controversial than congestion pricing, once your street gets announced.”

A meeting last week in Eagle Rock on a rapid bus lane between North Hollywood and Pasadena erupted in shouting. A Metro hearing on a similar project drew more than a dozen Valley homeowners who said the bus line would destroy their property values.

Advocates have also urged an expansion of “all-door boarding,” which allows riders to enter through any door on two of Metro’s busiest rapid bus routes on Wilshire and Vermont.

The strategy could reduce wait times by 42 seconds when 30 people board at one stop, a Metro analysis found. The strategy could make sense on other busy lines, Cheung said, but he said he could not yet say whether it would be expanded.

Riders to Metro: Just run more buses

Julia Griswold’s worst days used to start with a Metro bus that pulled away from the stop just before she arrived, or blew past without stopping. Once she boarded, sweaty and stressed, she would fret about being fired from temp jobs and think, “I don’t have money, so I don’t matter. No one cares if I get to work on time.”

Last summer, Griswold bought a used Chevy Spark for $9,000. The purchase was worth it, she said, but without a full-time job, she would not have been able to afford it.

For everyone who can’t, she said, Metro needs to run buses frequently enough to eliminate “the humiliation of running as fast as you can to catch a bus, and watching it pull away as you’re gasping and sweating.”

“It should matter that thousands of people a day can get where they’re going easily,” she said. “If the bus is only coming every 48 minutes, you’re really screwed. But chances are, you’re really screwed if you’re relying on that bus anyway.”

Over a decade, the number of hours that Metro buses spent on the street fell 10%, mostly during the Great Recession. Scheduled service hours fell from nearly 7.78 million in the 2008 fiscal year to 7 million in 2018, according to budget documents.

Rail service hours nearly doubled over the same time period, to 1.25 million hours, as new lines opened to East Los Angeles, Azusa and Santa Monica.

The new Measure M sales tax is expected to raise more than $160 million annually for transit operations. Metro should use those funds to improve frequency and lower fares, as it did during periods of high ridership in the mid-1980s, said Denny Zane, the executive director of the transit advocacy group Move L.A.

“The spending suggests the agency has been captured by the excitement over rail,” Zane said. “But we can’t lose sight of people who need transit service now. Metro can afford to do both.”

Cheung said Metro is considering more frequent service on routes that are conducive to trips of less than two miles. Those trips — to a daycare, a laundromat, or a grocery store — represent 46% of the county’s travel, but just 2% are taken on transit, he said. Most are made outside rush hour, in the afternoon or evenings, when buses run less frequently.

Metro could see an additional 500,000 trips per day if its share of short trips tripled to 6%, more than enough to make up for recent ridership declines, Cheung said.

But it would require running buses frequently enough that riding would be faster and easier than walking, biking or driving. Metro is considering designing bus routes that stop more often within major commercial and residential centers, and stop less often outside those areas.

Though Los Angeles voters have agreed to raise sales taxes twice in 10 years to pay for more transit, few ride the bus or train themselves — which, transportation experts ruefully note, sounds like an excerpt from a now-infamous headline in the Onion: “Report: 98 Percent Of U.S. Commuters Favor Public Transportation For Others.”

And shifting those habits will be a challenge. When someone buys a car, they become less likely to take transit and more likely to drive, studies show. Non-car owners now have more alternatives than ever, including Uber and Lyft, car-sharing services like Zipcar, and rental bikes and scooters.

Although Esparza, the CSUN student, is taking transit again, she isn’t boarding as many buses. The final leg of her journey in the Valley is a local bus that runs twice an hour. If she misses it, her trip could be an hour longer. Now, she’s more likely to call an Uber.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.