The ‘bad old days’ in Boyle Heights are gone, but for how long?

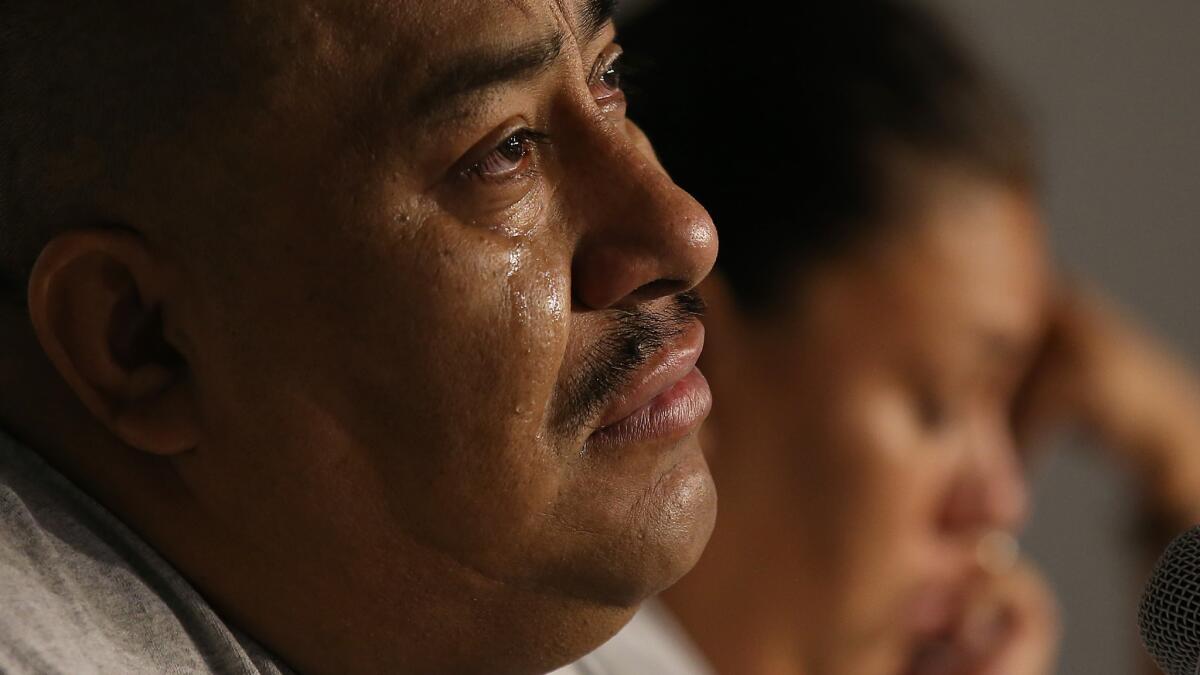

Last month, Los Angeles police officers fatally shot 14-year-old Jesse Romero in Boyle Heights during a foot chase.

The shooting — one of five at the hands of police in the Eastside district this year — sparked a protest outside the Hollenbeck police station that drew about 30 people who demanded answers and condemned the violence.

Later that night, more than 100 people converged on the same spot. But instead of protesting, they came to watch a screening of “Kung Fu Panda 3” hosted by the Los Angeles Police Department for families.

The LAPD has focused much effort in the last decade on reaching out to the Eastside neighborhood, part of a citywide community policing effort that department brass cited as one factor in a dramatic drop in crime there. Once a hub of gang violence, the neighborhood has seen homicides and other violent crimes plummet compared with levels in the 1990s.

But over the last two years, crime has been creeping up again, both on the Eastside and citywide.

The shooting of Romero on Aug. 9 — along with several other high-profile police shootings — is testing the LAPD’s effort to continue the strong community relations. Spread over just six square miles, Boyle Heights has had more fatal on-duty police shootings this year than any other neighborhood in Los Angeles, according to data compiled by The Times.

And the two youngest people shot by LAPD officers this year died in Boyle Heights: Romero and a 16-year-old, Jose Mendez.

The five Boyle Heights shootings make up more than a third of the 14 deadly shootings by on-duty LAPD officers in L.A. so far this year. By comparison, there were three people shot by on-duty LAPD officers in Boyle Heights last year, one of whom died.

An LAPD officer was shot in the arm during one of the deadly encounters in Boyle Heights this year.

Like many neighborhood shootings, the killing of Romero is fraught with conflicting accounts.

Romero was with two others behind an apartment complex, tagging gang-type graffiti when gang officers approached, the LAPD said. The three bolted, police say, with Romero “grabbing his front waistband.”

As they approached Breed Street, officers heard a gunshot, the LAPD said, adding that a witness saw Romero fire a handgun in the direction of the pursuing officers.

In a statement released Friday, the LAPD said that as “one of the officers looked south on Breed Street from the southwest corner, he saw Romero crouched on the sidewalk with his right arm extended toward the officer. Fearing Romero was going to shoot at them, one officer fired two shots at Romero, striking him twice.”

One woman, however, said she saw the teenager throw a gun toward a fence and then heard gunfire.

Romero’s mother said she didn’t think her son was involved in a gang, though posts on social media show the boy throwing gang signs and tributes from friends indicated he was a member of the Tiny Boys, whose graffiti pocks the sidewalks and power poles along streets near where Romero lived.

But, one of Romero’s friends emphasized, the teenager was also “someone’s son, a brother, a friend.”

“He was a human being and he meant something positive to many of us who knew him,” the friend wrote in an anonymous letter that was read at a recent rally. “I don’t want Jesse to be remembered as a gang member or a crew member.”

Many residents say Boyle Heights feels safer than in the past. People feel more free to walk in their neighborhoods at night, and the once common sound of gunfire has definitely abated, they say. The district has seen a controversial though still early creep of gentrification that has brought new businesses into the predominantly working-class Latino neighborhood, something many believe possible because Boyle Heights doesn’t have the level of gang crime and other violence it had a generation ago.

In 1992, the LAPD’s Hollenbeck Division, which patrols Boyle Heights, had 97 homicides and about 57% of those were gang-related. Last year, there were 12 homicides — 83% gang-motivated or related, according to LAPD Det. Jose Ramirez, a homicide investigator in the Hollenbeck Division.

The crime rise over the last three years has been noticed across the community, even if it’s still small compared to the 1990s. Violent crime has risen 57% through Aug. 27 compared with the same period in 2014, according to LAPD statistics.

Rosa Garcia said she has worked to keep her children away from other teenagers affiliated with gangs. But the shootings of Romero and Mendez, the 16-year-old shot in February, also make her wonder whether her children have something to fear from the police.

“Just because you have a badge, you have the right to draw your gun and kill?” she asked. “One is more scared of police than gangs because no one knows how police are going to react.”

Others see the police as a partner. Margarita Amador, a lifelong Boyle Heights resident who sits on the neighborhood council and a community police advisory board, said that Romero was carrying a gun when he was killed and that he has inaccurately been portrayed as an innocent victim.

“It’s a community problem more than a police problem. We can’t point fingers. We have to work together,” she said. “The officers that work at Hollenbeck, they don’t wake up in the morning to say, ‘I’m going to come and kill a 14-year-old.’”

Neighborhoods like Boyle Heights have a long history of activism and protests, including criticism of law enforcement. On Monday, another vigil was held over the shooting of Romero on the 43rd anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium, a mass protest by mostly Mexican Americans from Eastside neighborhoods against the Vietnam War and in support of civil rights.

But there has also historically been a strong counterweight of support for police in the neighborhoods, influenced partly by the large number of officers who have personal ties to the neighborhood or whose backgrounds mirror the working-class, largely Latino immigrant community.

Across the LAPD, nearly half of the sworn officers are Latino, almost perfectly matching L.A.’s demographics.

The LAPD also worked to ease tensions in certain neighborhoods, including in and around the Ramona Gardens public housing development, which for many years was the scene of physical confrontations between police, gang members and some residents who accused officers of heavy-handed tactics. Police officers in turn said that for years going into the neighborhood without backup was dangerous because of the risk of being shot at and ambushed by gang members.

In recent years, the LAPD has cultivated stronger ties to that neighborhood, and gang activity has declined as police and residents interacted more, including through community and athletic events like baseball games. LAPD officers now coach a football team and lead a Girl Scouts troop in the housing project.

LAPD Capt. Martin Baeza said he believed the shootings by officers in Boyle Heights were the result of the increased violence in the neighborhood and surrounding communities. Sixty-six people have been shot in the LAPD’s Hollenbeck Division this year, more than double from the same period in 2015.

There’s a consequence to people not remembering the bad old days: We’re kind of seeing a resurgence of the bad old days.

— Father Greg Boyle

Each of the five people killed in police shootings were armed with either a gun or a knife, the LAPD has said.

“I completely understand how certain members of the community are in outrage that a 14-year-old was shot, because it is tragic,” Baeza said. “But I think what we need to do is work together and address the violence that leads to a young person getting killed, whether it’s by another person or an officer-involved shooting.”

A major problem, Baeza said, is a resurgence in gang activity in Boyle Heights, the cradle of some of the city’s oldest gangs. In June, a 10-year-old girl was struck in the head during a drive-by shooting. In August, a 26-year-old man was fatally shot after confronting two taggers.

Still, some in the community question whether the LAPD is too quick to resort to violence.

Mendez, the 16-year-old, was the first person fatally shot by police in Boyle Heights this year. Police say he was driving a stolen vehicle and carrying a sawed-off shotgun that he pointed at officers.

In April, an officer shot and killed Arturo Valdez, a 27-year-old who police say broke into an 82-year-old man’s home and took him hostage. The officers saw Valdez holding a knife to the man’s neck and thought he was going to kill him, police said, prompting one officer to shoot.

A month later, police say, Robert Mark Diaz, 28, fired a handgun at gang officers after a short chase, striking one in the arm. The other officer returned fire at Diaz, who died at the scene.

In late July, an officer working a gang unit fatally shot Omar Gonzalez, 36, after a short car chase that abruptly ended in a cul-de-sac. Police say Gonzalez got out of the car and fought with officers while armed with a handgun.

Both police and residents say they have noticed another troubling trend: The gang members are getting younger, some just creeping toward the edge of puberty.

Father Greg Boyle, whose gang outreach efforts began decades ago at a Boyle Heights church, said he believed up-and-coming gang members had forgotten how violence ravaged the neighborhood decades ago. He pointed to the late 1980s and 1990s — a time Boyle calls “the decade of death.”

Back then, Boyle said, people who saw the killings and shootings first-hand grew weary of the violence and began to shy away from gangs. Now, he said, that memory has faded.

“Now you have a generation that’s born with no collective memory of how terrible it was,” he said. “There’s a consequence to people not remembering the bad old days: We’re kind of seeing a resurgence of the bad old days.”

Boyle said he’s surprised by the number of people fatally shot by police in the neighborhood because despite a bump in crime, the levels of violence still don’t match what happened a generation ago. And the LAPD has evolved from the much harsher tactics it employed back then.

The priest said he has buried more young people shot dead by police in the last year than he can remember.

“I never did that before. Didn’t do it 20 years ago, even in the worst period,” Boyle said. “Are things better in terms of community policing relations? Absolutely, there’s no question of that. We’re in a good period, which is the head-scratching part.”

At the same time, Boyle said he was surprised by the protests over the Romero shooting.

“It sort of doesn’t happen here very often,” he said. “There were other things and people were upset, but you didn’t see people gathering and marching.”

Boyle said what everyone could agree about was that no one wanted a return of the “bad old days” when the Eastside, like much of L.A., was convulsed by the kind of violence that saw more than 2,000 people killed in the county some years.

“You carry that with you,” he said. “Even though things have been calm, you still in the marrow of your bone remember what it was like and it’s still kind of present. So people aren’t as shocked by things.”

Twitter: @brittny_mejia

Twitter: @katemather

Times staff writer Ben Poston contributed to this report.

ALSO

This Mojave Desert solar plant kills 6,000 birds a year. Here’s why that won’t change any time soon

California’s heavy water users could face penalties if drought persists

A flawed missile defense system generates $2 billion in bonuses for Boeing

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.