A massive 895-home development on Southern California’s coast is shot down

Olga Zapata Reynolds of the group Saving Banning Ranch Together speaks about Wednesday’s vote.

After a marathon day of testimony, California coastal commissioners voted to deny a controversial proposal to develop one of the largest open private parcels of land on the Southern California coast.

The 9-1 vote came at about 10:30 p.m. Wednesday, more than 11 hours after the hearing started. The proposed development called for construction of 895 homes, a hotel and shops on an Orange County oil field overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

The denial was more an expression of frustration with competing staff and developer proposals for Newport Banning Ranch than an outright rejection of the project.

“I don’t think if we support denial today that’s the end of this project,” commission Vice Chairwoman Dayna Bochco said before the vote.

The developers can submit a new proposal in six months or challenge the decision in court. “We are extremely disappointed. It is too early to speculate about our options,” said Banning Ranch spokesman Adam Alberti.

The project intensified public outrage over the commission’s dismissal of Executive Director Charles Lester this year — and perceptions that a leading reason for the ouster was Lester’s unwillingness to cave in to pro-development pressure.

Last fall, the commission’s staff experts recommended denial of Banning Ranch’s proposal for a 1,375-home and hotel project on the grounds that the site, though disturbed by nearly 70 years of oil production, remained a crucial ecological refuge for plants and animals all but gone from coastal Southern California.

Embracing the developers’ arguments that the land was a blighted industrial site in need of restoration, commission Chairman Steve Kinsey and others on the panel pressured the staff in emails and during hearings to reevaluate its environmental assessments.

Staffers backpedaled this spring and recommended approval of a smaller project on as many as 55 acres.

Then in another twist, the staff late last month said the development’s footprint needed to shrink to about 20 acres to avoid destroying foraging habitat for burrowing owls that winter on Banning Ranch.

Acting Executive Director Jack Ainsworth acknowledged that the staff was late to stake out the owl habitat. “We do have to own that,” he said Wednesday, but added that it was important to consider all the facts, regardless of when they were presented.

“Your decision is one of the most important decisions this commission has faced in its 40-year history,” Ainsworth told the commissioners. “It’s critical you get it right.”

Controversy has stalked the commission this year, and the vote’s outcome likely hinged in part on one of the most contentious issues — the practice of holding private meetings, also known as ex parte communications, with parties who have an interest in a project.

Kinsey left the dais during the Banning Ranch discussion. He was forced to sit out the vote because he met privately with Banning Ranch developers and never reported it, as required by the Coastal Act.

Commissioner Mark Vargas was eight months late reporting a meeting he and several other commissioners had with project opponents. But a commission attorney advised Vargas at the hearing that he did not need to recuse himself. So he didn’t.

Commissioner Wendy Mitchell, a political consultant and friend of Susan McCabe, an influential lobbyist on behalf of developers, did not attend Wednesday’s hearing.

Commissioner Roberto Uranga was the sole yes vote Wednesday.

The latest staff recommendations would have permitted roughly 480 multifamily and single-family homes in two clusters on the property’s east-central edge, as well as creation of a 329-acre nature preserve centered in the tract’s northern wetlands.

The hotel, a road from Pacific Coast Highway and about 400 residences planned for the southern half would have been dropped — cuts that the development team denounced as a de-facto denial of the project and an unconstitutional property-taking.

The staff proposal “goes too far” and produces an “unbuildable project,” said Banning Ranch consultant Steven Kaufmann, an attorney who represented the Coastal Commission from 1977 to 1991 while working in the state attorney general’s office.

The fight over one of the biggest developments to go before the commission in years has revolved around the staff’s identification of much of Banning Ranch as environmentally sensitive habitat area, or ESHA, a key Coastal Act protection.

Under the act, only resource-dependent uses such as nature trails or low-impact camping are allowed in environmentally sensitive areas. Courts have ruled that housing development is not permitted, and the staff maintained that a large-scale project would violate coastal law.

Project supporters argued the habitat is highly disturbed and insisted that unless the project moved forward, the 401-acre tract would remain a fenced-off oilfield closed to the public for decades to come.

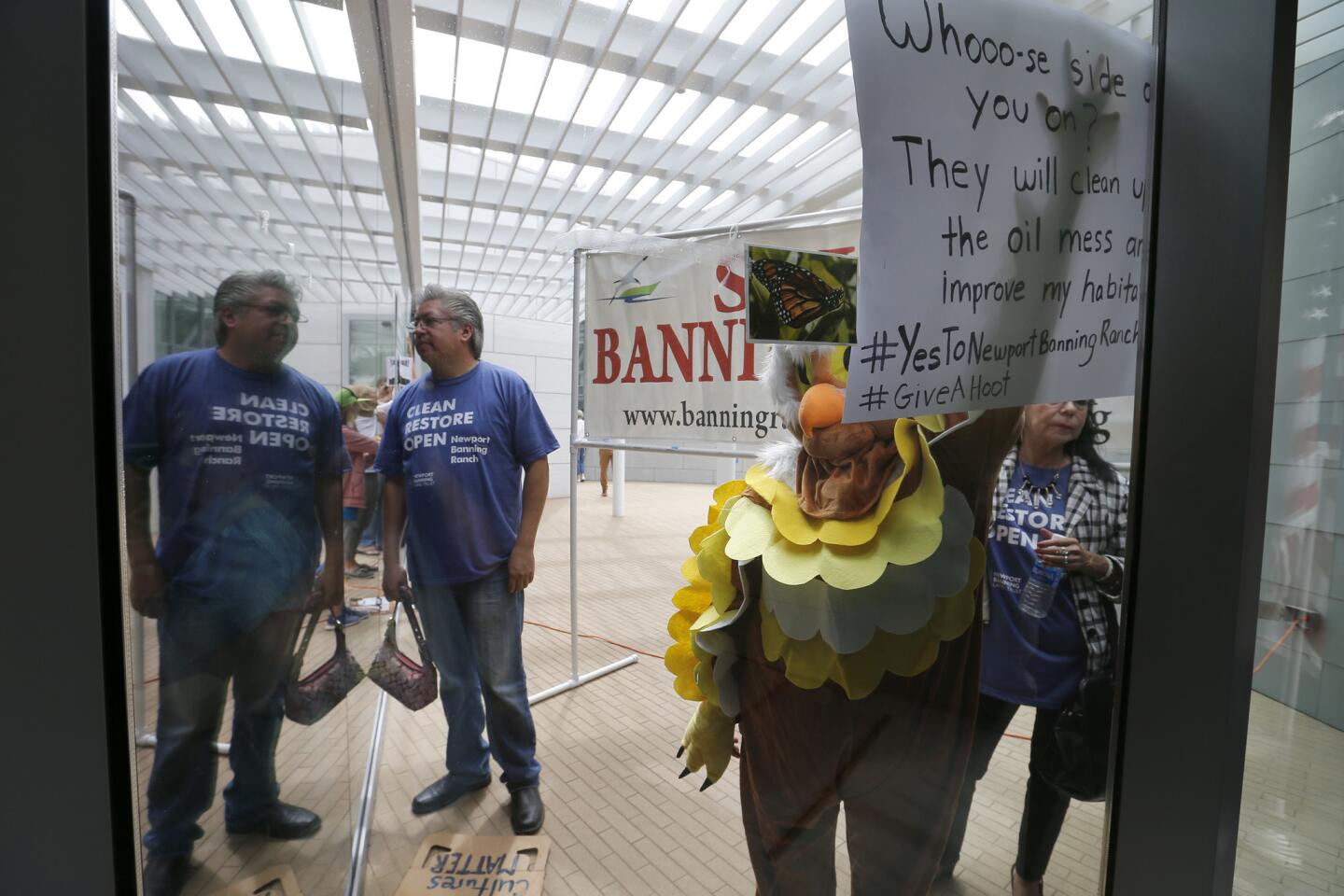

The development team’s websites, videos and news releases wrapped the proposal in green, portraying it as a “progressive environmental project” that will restore and open to the public a prized piece of coast.

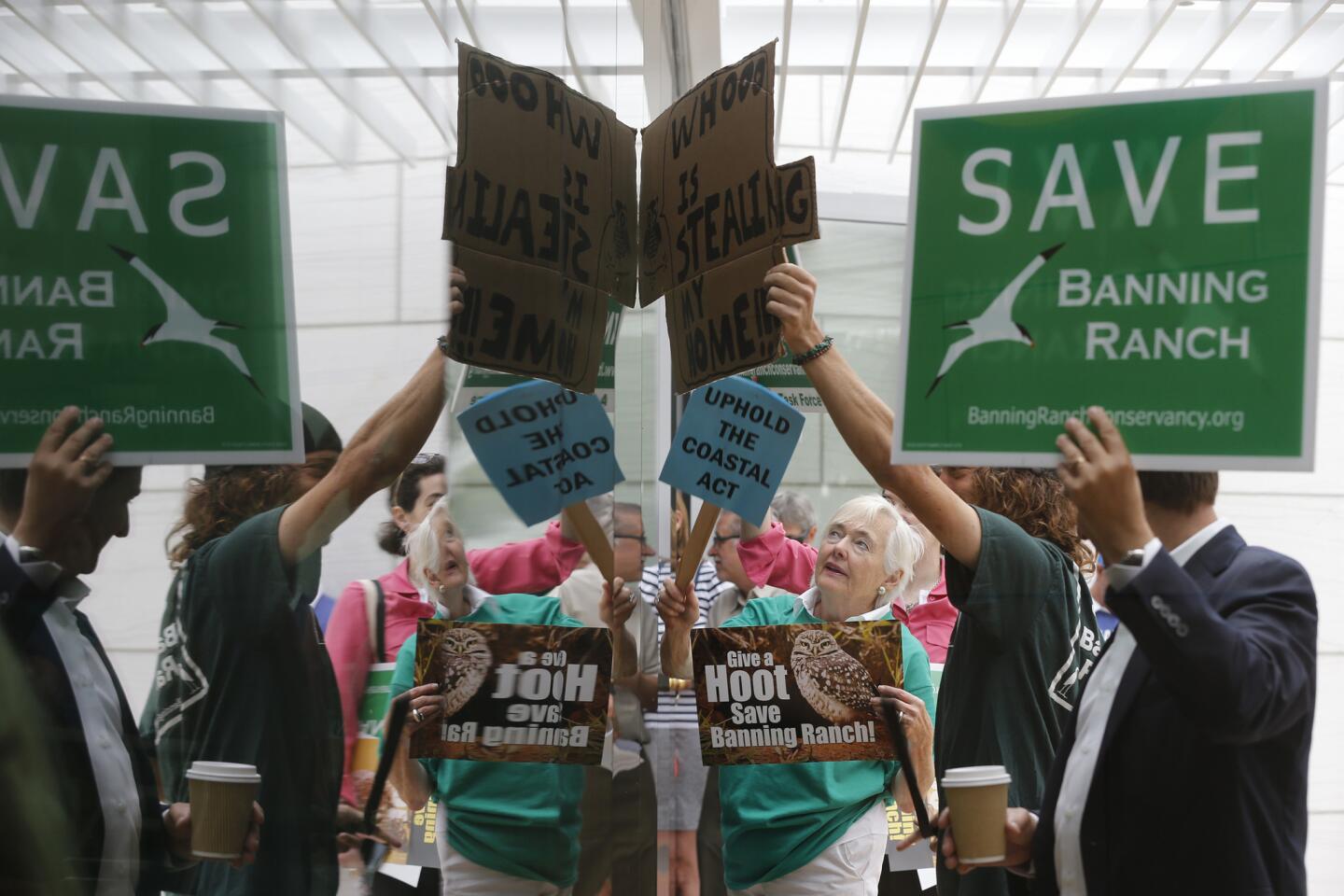

Hundreds turned out for Wednesday’s hearing at the Newport Beach City Council chambers, spilling into an overflow room.

Proponents wore hats and T-shirts that proclaimed “Clean Restore Open.”

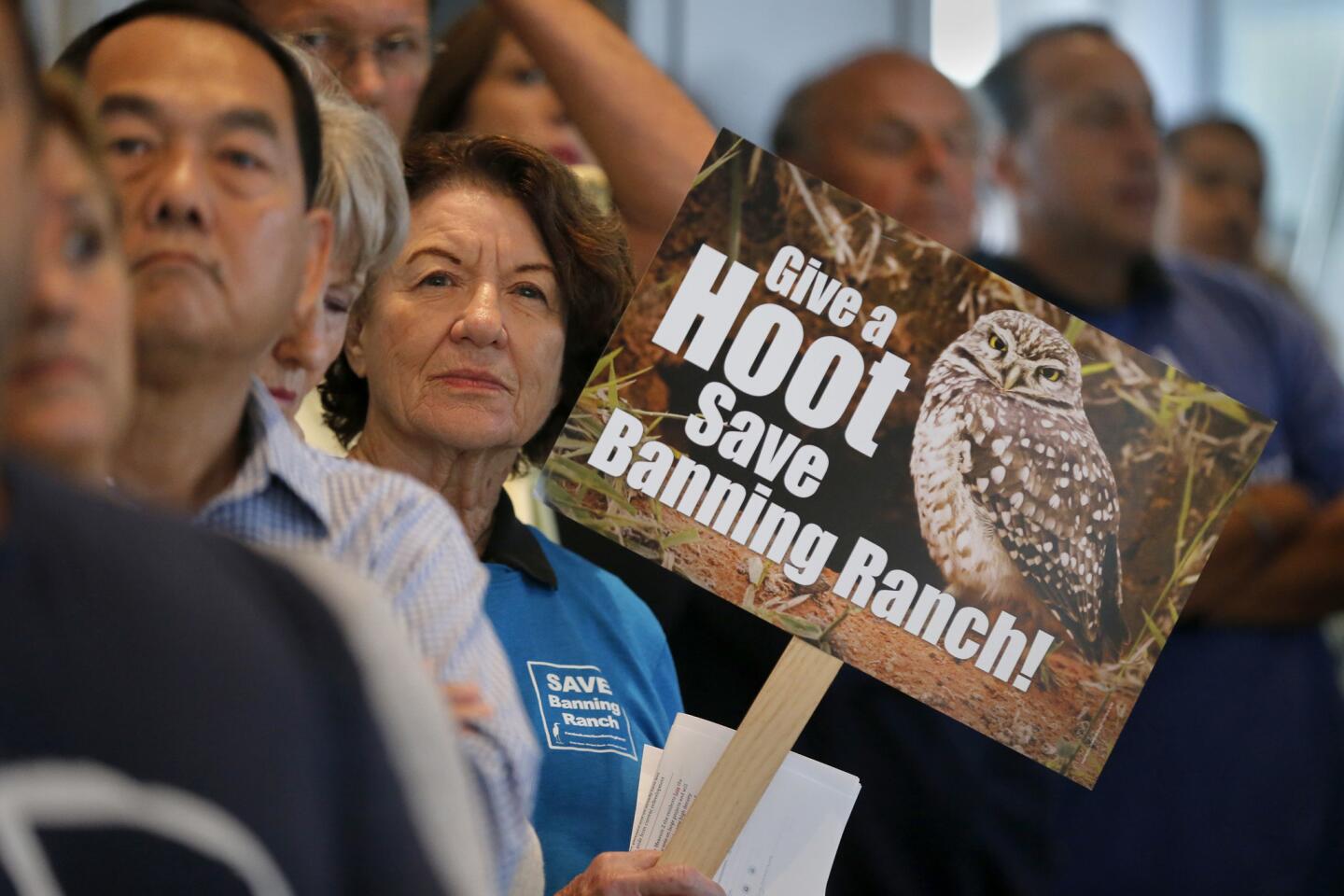

Opponents, including members of mainstream and grass-roots environmental groups, showed up with a live burrowing owl and waved signs saying “100% Open Space” and “Save Banning Ranch.”

The supporters included 20 to 30 people bused in by Aera Energy, the oil company that has co-owned the property for nearly two decades and is one of the development partners.

Aera has not been involved in oil production at Banning Ranch, but as a land owner has been named in several environmental orders dealing with the dumping of oil waste, the destruction of wetlands and wildlife habitat and the drilling of unpermitted wells.

Staff environmental scientist Cassidy Teufel told commissioners Wednesday that regardless of whether the project was approved, those orders require some cleanup and restoration at the site. He also said that on recent site visits, the state Division of Oil, Gas & Geothermal Resources found that rubble from abandoned wells was improperly dumped on the upland areas and needed to be removed.

ALSO

Garcetti vows to bar private meetings with planning commissioners

Mountain resorts, rent subsidies and saunas: The benefits of living in a city plagued by scandal

UPDATES:

11:20 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details.

This article was originally published at 10:45 p.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.