He shot his childhood friend in the back of his head — as a favor, he says

Beong Kwun Cho stood with a cocked Smith and Wesson revolver in his hand.

Crouched less than a foot away was his childhood friend, a man he’d known for more than three decades since they were schoolboys in South Korea. Years ago, Yeon Woo Lee had been the one to carry the hahm, the chest full of gifts, at Cho’s wedding -- the equivalent of a best man.

Now, Lee was on his knees.

Cho’s mind ran through the events that led them to this moment, in the dead of night on a sparse industrial corner of east Anaheim, miles from the cheery glow of Disneyland. He waited for one bicyclist to pass, then another. He heard the rumble of an approaching train.

He squeezed the trigger, then it was over. He watched his friend slump forward.

Prosecutors call it first-degree murder. Cho says it’s not that simple.

::

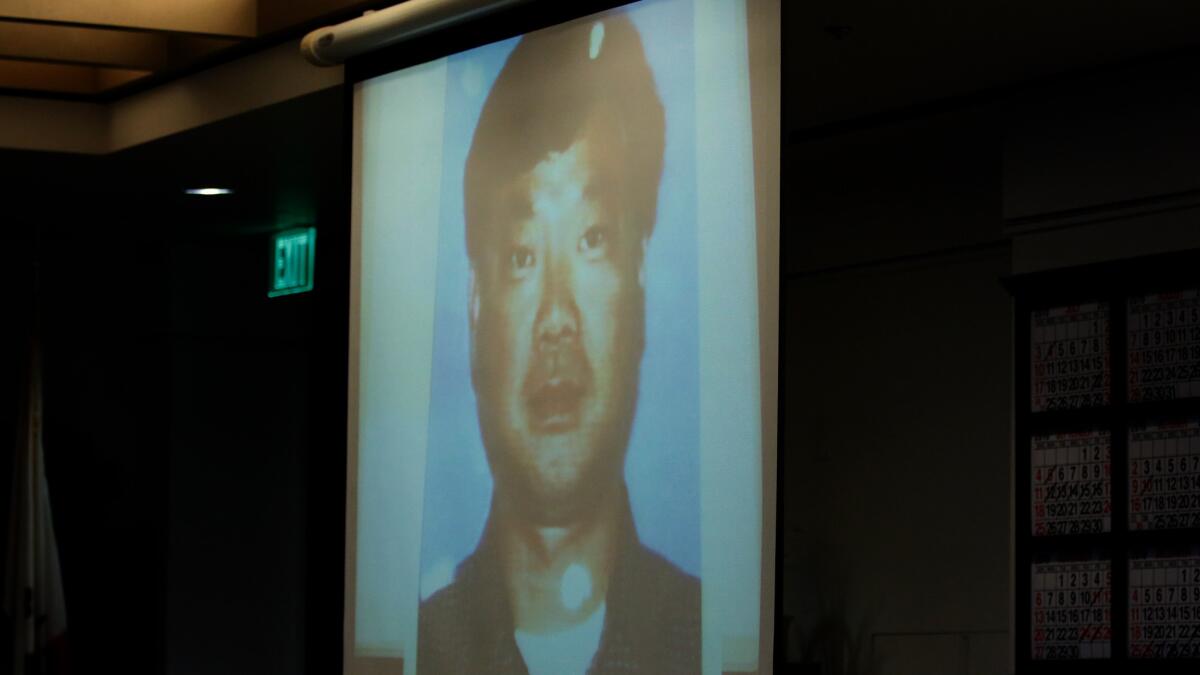

A street sweeper discovered the body of Lee, a 50-year-old South Korean national with bulbous eyes and round cheeks, before dawn Tuesday, Jan 25, 2011.

The man lay next to his rental car, blood pooled around his head. On his back were large, muddy footprints and next to his body, a cigarette butt, a flat tire and a jack.

To investigators, the scene seemed self-explanatory: A tourist unfamiliar with the area was changing a flat tire on a poorly lighted street when an attack or accident befell him. But when detectives sent the body out for an X-ray of the head wound, they saw the single bullet that had pierced his brain, back to front, before lodging in the front left side of his skull.

Records at E-Z Rent-A-Car led investigators to Room 146 at Howard Johnson, where the owner said Lee had paid cash and asked to be kept off the registration books. Detectives next retraced his steps to a Fullerton motel he’d stayed at earlier. He had listed two 714 phone numbers. One was for a prepaid “burner” phone.

The other took them to a sand-colored home in Cerritos.

Around midnight, less than 24 hours after Lee’s body was found, Cho answered the door at the home where he lived with his wife and two daughters. He agreed to help investigators and drove himself to the police station.

“Looks like it is something important?” Cho asked in Korean, feigning confusion.

Cho claimed that he’d last seen his longtime friend, who was visiting from South Korea, during dinner at a sushi restaurant Monday night. He’d been calling Lee all day Tuesday, and thought it was strange he couldn’t get in touch with him, he told homicide detective Julissa Trapp and a Korean-speaking officer. He thought perhaps Lee had abruptly left for South Korea, Cho told the detectives.

A couple of hours into the interrogation, Trapp switched her tone.

“I think that something happened between you and Mr. Lee Monday night,” she said. “I think you can explain. OK, maybe -- maybe it was an accident.”

Cho hemmed and hawed. Then he said he was ready.

“Could I smoke a cigarette for a moment and then explain everything as it is?”

::

Cho’s two daughters grew up considering Lee an uncle, he said. Their families vacationed together. The two men did business together.

Then a few months ago, Lee asked Cho for a favor he wasn’t sure he could do, even for his closest friend, he told the detective.

Lee’s motel business in South Korea was foundering. His marriage was falling apart. Lee told Cho he wanted to die, but didn’t want to burden his family with the trauma and social stigma that comes with suicide, Cho said.

Lee tried to hire people he’d met at nearby casinos to kill him and make it look like a random crime, Cho said, but they demanded payment ahead of time and he didn’t trust them to go through with it. Ultimately, he turned to his best friend.

“He said there is no other way -- this is the only way,” he told Trapp.

His friend, Cho told police, orchestrated the entire scenario. It was Lee who procured the gun and a box of ammunition. Lee drove around scouting out possible sites, choosing a couple spots near bodies of water because he was superstitious. Lee arranged for them to go to a gun range together for target practice, and took Cho to a Wal-Mart where he bought black knit gloves and size 13 shoes — props to make his death look like a robbery.

Lee then chose the date for the deed, Cho said: his wife’s birthday. It would be his last gift.

After dinner that night, they each drove their respective cars to the first spot Lee had picked out, between Anaheim Lake and a basin, only to find that there were crews working there late into the night. They drove to a second location nearby, a quiet stretch of Miraloma Avenue.

Lee flattened the tire, ransacked the glove compartment of his rental and smoked a final cigarette. He handed Cho the revolver wrapped in a T-shirt before dropping to his knees with his back to his friend, Cho said.

“Keep talking to me so that I won’t know when I’m being shot. And while I’m talking … shoot me in the middle of our conversation,” his friend implored, Cho told the detective.

::

As the interrogation stretched into the wee hours of the night, Trapp pressed Cho.

She didn’t believe Lee wanted to commit suicide, the detective said. He had purchased plane tickets to return to South Korea and sent his wife flowers and a letter saying he was coming home, Trapp pointed out.

“Why is he going to spend the money if he knows he’s going to die?” she asked.

Cho’s story grew stranger. While maintaining that Lee wanted to die, he began enumerating reasons he’d grown to resent his longtime friend over the years.

Cho said his family lost their home to debt collectors in South Korea years ago as a result of a bad business deal Lee made, for which Cho was the guarantor. In recent months, Cho said, Lee was blackmailing him, threatening to get Cho and his family deported from the U.S. if Cho didn’t go along with his demands.

Then about a month before his death, Lee came over to Cho’s home to drink and passed out on the couch. In the middle of the night, Cho said, he awoke to find Lee, drunk and naked, in their bedroom. Lee, he said, was sexually assaulting his wife.

Embarrassed, confused and afraid, Cho said he pretended to be asleep.

“I want to know,” Trapp responded, “as a husband, a father, as a man, as the head of the household, how did you feel?”

“I wanted to kill him,” Cho said.

::

Cho’s first-degree murder trial began this month in a top-floor courtroom in downtown Santa Ana.

The bulk of the prosecution’s case was nearly nine hours of Cho’s videotaped interrogation, in which he admitted shooting his childhood friend in the back of the head, and to thinking his life would be better if Lee was gone.

“Because I hated him,” jurors heard Cho tell Trapp unequivocally. “He... he wanted it and I hated him … He wanted it so bad.”

Suicide is a sign of failure of moral upbringing, so it stigmatizes the whole family.

— B.C. Ben Park, Penn State professor, speaking about Korean culture

Cho’s defense attorney, deputy public defender Robert Kohler, told the mostly non-Korean jury that cultural context could help them make sense of what may seem an improbable story.

“There’s a strong stigma attached to suicide,” B.C. Ben Park, a Penn State professor who has researched Korean attitudes toward suicide, told jurors. “Suicide is a sign of failure of moral upbringing, so it stigmatizes the whole family.”

Seong-han Hong, a friend who had known both men since middle school, described how Lee had a domineering personality and usually got his way in the decades of their friendship, especially when it came to Cho.

Cho, he said, “was manipulated by others easily…. He doesn’t know how to say no to other people.”

Kohler also called to the stand Cho’s wife.

The woman looked neither at her husband, who wiped away tears with trembling hands in the defendant’s seat, nor at the jurors weighing his fate as she testified in a barely audible voice.

Years ago in South Korea, she said, Lee made a pass at her, which she rejected. Then about a month before his death, Lee drunkenly came into the room where she and her husband were sleeping and touched her inappropriately, the woman said.

She fought him, but didn’t make a sound or wake her husband because she was ashamed, she said.

In the following weeks, Lee raped her, she said. Twice. But she never told her husband about any of the incidents.

“That’s how I grew up,” she said through a translator. “I grew up in Korea. Even if I was raped, that’s not something I can even tell my friend. I was embarrassed and ashamed.”

::

His hair grayer and thinner than in his mugshot from five years ago, and his cheeks a little hollower, Cho, now 56, sat through the two-week trial in a gray pinstripe suit, mustard tie and glasses.

He listened to his daughters describe him as a calm family man who was never violent nor ever raised his voice. He listened to his wife, who has since filed for divorce, describe being assaulted by his friend and being unable to ever talk to her husband about it. He listened to himself lie to police, then admit to killing his friend and pointing detectives to where in his garage they’d find the gun stashed.

Were you thinking of saving him when you put the gun to the back of his head and pulled the trigger?

— Scott Simmons, deputy district attorney

He watched the surveillance footage showing Lee and himself at Wal-Mart purchasing the shoes and gloves, and the two men, each in their own car, meeting up and conversing at a gas station shortly before the shooting.

He listened to a stipulation about life insurance policies Lee had obtained in South Korea, including a $500,000 one issued in December 2009 that would not have been paid out in the event of a suicide within two years.

On Monday, he took the stand in his own defense.

Right up to the last moment, he never thought Lee would go through with the plan, Cho said.

“Whether I liked him or I hated him, he was a friend,” he said. “I was begging him, let’s stop this. I was trying to save him.”

“Were you thinking of saving him when you put the gun to the back of his head and pulled the trigger?” Deputy Dist. Atty. Scott Simmons asked.

Cho testified that it was only when Lee insulted his wife and his daughter that he pulled the trigger.

If jurors decide Cho did not intend to kill his friend until the moment he pulled the trigger, that he shot in the “heat of passion,” they have the option of finding him guilty of voluntary manslaughter. If they doubt that story and instead find that he decided earlier to kill the man, they could convict him of first-degree murder, for which he could get up to a life sentence.

Jurors began deliberating Thursday morning.

Whatever they decide, the friendship that spanned more than three decades, survived financial debacles and crossed the Pacific ends with one dead on a roadside in Anaheim and the other in a California prison cell.

Cho said he left behind the man he once considered closer than his siblings and his parents, even his wife, and drove into the night, not once looking back.

“I realized, I did it,” he said. “I did it.”

For more California news, follow me on Twitter @vicjkim

ALSO

Court commissioner calls Venice boardwalk cleanups ‘troubling,’ refuses to punish homeless advocate

In Westlake, homeless people take cues from immigrant street vendors

UPDATES:

12:20 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details and to reflect the start of jury deliberations.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.