Man accused of murdering college student is freed after 11 years: How the case against him unraveled

Raymond Lee Jennings vowed that God would view him as an innocent man.

“This is one sin that I will not be judged for,” he told the court at his 2010 sentencing. “I’m at peace in my life and I laugh and I smile because I hold no remorse.”

But a jury had already convicted him of the 2000 murder of Michelle O’Keefe. The teenager was shot to death inside her blue Mustang in a Palmdale parking lot in a case that went unsolved for several years and drew national attention.

After a judge sentenced Jennings to 40 years to life in prison for second-degree murder, the former Army National Guardsman and Iraq war veteran filed an appeal, but lost. California’s Supreme Court then refused to review the case, and he seemed out of legal challenges.

But in an astounding reversal last week, Los Angeles County prosecutors asked for Jennings’ immediate release from custody, saying they’d discovered new evidence that not only cast doubt on his guilt, but seemed to implicate another person. It marked the first big case handled by the district attorney’s office’s new unit dedicated to overturning wrongful convictions.

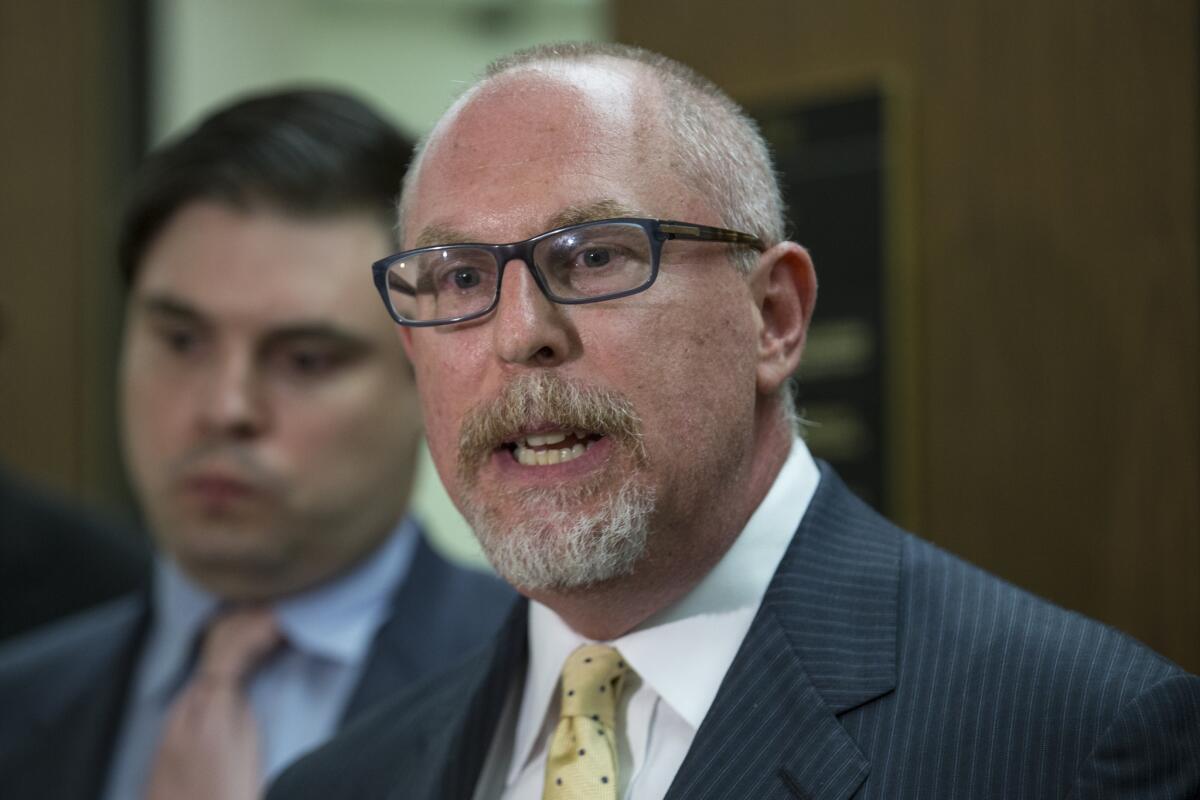

After a hearing Thursday when a judge ordered Jennings’ release, his attorney, Jeffrey Ehrlich praised the development, but condemned the “cascade of errors” in the investigation that initially led to his client’s arrest and conviction.

“Ray Jennings is not a murderer,” Ehrlich said. “He was a witness to an awful, senseless, brutal crime.”

The case, which is laid out in court documents, traces back to a winter night in 2000.

Soon after 9:20 p.m. February 22, O’Keefe, 18, arrived at the park-and-ride commuter lot in Palmdale. She had just carpooled back to the Antelope Valley from Los Angeles with a friend after appearing as an extra in a music video for Kid Rock.

As her friend drove off, O’Keefe moved her Mustang, which had been parked under a light, to a more discrete spot. She needed to change out of her tube top and skirt before heading to a night college course.

Then, gunfire echoed through the darkness.

Jennings, who had just started as a security guard patrolling the lot, radioed to his supervisor to report the shots.

As his supervisor drove toward the Mustang, spotting O’Keefe’s body slumped over the steering wheel, Jennings took cover. He eventually joined his boss near the car.

Before long, sheriff’s investigators arrived on the scene to collect evidence. Jennings told them he’d been patrolling on foot when he heard a car alarm and then gunshots. He said he hadn’t seen the shooter.

During another interview at Jennings’ home a month after the murder, detectives told him they’d received a statement from a woman who said she’d talked to him after the shooting. Jennings confirmed the story — one he hadn’t mentioned during interviews at the crime scene — saying the detectives’ questions had jogged his memory.

It is inexplicable that he said the things he said if he didn’t have some involvement in the killing.

— R. Rex Parris, litigator and mayor of Lancaster

Billboards with O’Keefe’s picture and the message, “Can you help catch my killer?” popped up around the Antelope Valley, and the TV show “America’s Most Wanted” featured a segment on her killing.

Still, no arrests. More than a year and half after the killing, the lead detective described the case to The Times as “an absolute whodunit.”

Desperate for answers, O’Keefe’s family went on the Montel Williams show and met with a psychic, who told them their daughter had been killed by a big man with fair skin. The killer’s name, the psychic said, was either Leon or Lee — Jennings’ middle name.

From the Archives: Ex-security guard convicted in Palmdale parking lot murder »

Michael O’Keefe, Michelle’s father, found himself obsessing over what he believed to be premonitions. In a memory he recounted during a “Dateline” special on the case, he said his daughter was spooked when a license plate arrived in the mail for her Mustang.

The plate, he recalled her explaining, ended in the digits “187” — the penal code for homicide in California.

The case started to gain some traction after the family hired R. Rex Parris, a high-powered local litigator, and filed a lawsuit against the city of Palmdale, the security company hired to patrol the parking lot the night of the shooting and against Jennings.

Parris, now the mayor of Lancaster, bragged in court at the time that he planned to solve the crime during the civil trial. At one point, Parris questioned Jennings under oath in his office, and the attorney found himself convinced that the former security guard was the murderer.

He still stands by that hunch.

Innocent people are sometimes convicted of serious crimes. Ray Jennings is one of those people.

— Jeffrey Ehrlich, Raymond Lee Jennings’ attorney

“It is inexplicable that he said the things he said if he didn’t have some involvement in the killing,” Parris said in an interview last week.

In December 2005 — just after Jennings’ return from active duty in Iraq — authorities arrested and charged him.

The prosecution theorized that Jennings likely made an advance toward O’Keefe in the parking lot and killed her after he was rebuffed. They pointed to the $111 found inside her wallet as proof that it wasn’t a robbery.

In an interview this week, Robert Foltz, the former deputy district attorney who filed the murder case against Jennings, said the office initially rejected charges against the former security guard, but took a closer look at the evidence after receiving a phone call from O’Keefe’s family.

The former security guard’s actions suggested he had something to hide, Foltz said, mentioning Jennings’ decision to radio his supervisor instead of calling 911 after hearing the gunshots.

And yet, Foltz acknowledged it was “a problematic case,” saying there were issues early on with evidence collection — investigators, for example, didn’t collect Jennings’ uniform from the crime scene the night of the killing to check it for gunshot residue.

“There were a lot of things that should have been done that weren’t done,” he said.

At Jennings’ first trial in the spring 2008, the jury deadlocked — so did a second panel a few months later. But at his third trial in 2009, which unlike the previous two was held in the Antelope Valley not far from the crime scene, the jury deliberated for 12 days. Its verdict came back a week before Christmas: guilty of second-degree murder.

At his sentencing, members of O’Keefe’s family addressed Jennings through deep anguish, often quoting passages of the Bible. When Michelle O’Keefe’s younger brother, Jason, spoke, he read from the eighth chapter of John.

“If a man is a murderer and he doesn’t repent,” he read, “you belong to your father the devil.”

Later in the hearing, Jennings addressed the family and also evoked his faith.

The Homicide Report: A story for every victim »

“When the real killer is found, I forgive you for the insults that you said about my children and my parents,” he told O’Keefe’s family. “I forgive you for the hateful words that you have said.”

From behind bars, Jennings, now 42, filed an unsuccessful appeal and later learned that California’s Supreme Court had declined to look into his case. But his conviction had already grabbed the attention of Ehrlich’s son. The appellate attorney’s son had stumbled across the “Dateline” special on the case and told his father he was struck by what he perceived as weak evidence.

In October 2015, Ehrlich wrote a 34-page letter to the district attorney’s conviction review unit, arguing for Jennings’ release, saying he’d found “direct proof” of innocence and multiple flaws in the prosecution’s case.

“Innocent people are sometimes convicted of serious crimes,” Ehrlich wrote. “Ray Jennings is one of those people. Please, help him.”

Describing the case as an example of “investigative tunnel vision,” Ehrlich wrote that authorities homed in on Jennings and, inexplicably, didn’t take a close look at other people who were in the parking lot at the time of the shooting.

The prosecution’s argument that the case couldn’t have been a robbery because $111 was found in O’Keefe’s wallet didn’t hold up to scrutiny, Ehrlich said, explaining that the wallet had fallen into a crack between the seat and would’ve been hard to see in the dark. The attorney noted, too, that someone did steal O’Keefe’s cellphone.

At the hearing on Thursday, Deputy Dist. Atty. Bobby Grace, who is assigned to the conviction review unit, told a judge the office now believed someone else had committed the crime.

“We are prepared to say that the people no longer have confidence in the conviction based upon what we feel is third-party culpability,” Grace said.

Jennings smiled broadly.

Although he still has to wear an electronic ankle monitor because the case hasn’t been officially dismissed, Jennings was released from custody.

He spent the evening eating at Habit Burger Grill with his attorney.

Follow us on Twitter: @LAcrimes, @marisagerber

ALSO

4 men killed in series of shootings over the weekend in Compton

Still standing: L.A.-area homes that have survived crimes’ infamy

Families of Pomona homicide victims to march against violence

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.