Striking L.A. teachers are part of a national movement. But California is different

When Los Angeles teachers went on strike Monday, they followed a wave of strikes and demonstrations by teachers around the country.

In some ways, the L.A. strike is similar to those earlier actions. But there are also some big differences, as The Times reported earlier this month. The strike comes at a time when the L.A. teachers’ union is struggling against legal and political challenges to its influence and the increasing number of privately run charter schools, which compete with district-run schools for enrollment.

Here is a breakdown:

Why does the L.A. teachers’ union find itself at a crossroads?

For decades, United Teachers Los Angeles was the most influential force in the politics of the school system. But it has been unable, in recent elections, to match the campaign spending fueled by wealthy donors who support charter schools. These privately operated, mostly non-union schools now serve about 1 in 5 students enrolled in L.A. public schools. L.A. has more charters than any other school system.

The rapid growth of charters has created an alternate constituency of parents who support charters and may resent the dark way the union casts their schools.

FULL COVERAGE: LAUSD teachers’ strike »

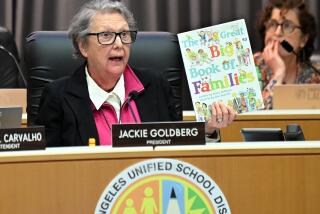

In 2017, for the first time, charter-backed candidates won a majority on the L.A. Board of Education.

A Supreme Court ruling last year also has deprived UTLA, along with other California unions, of the right to collect fees from all teachers within its jurisdiction. Union membership — and the accompanying dues that fuel campaigns — essentially have become optional.

How does the L.A. strike fit into national movement?

Many of those strikes occurred in red states, including Oklahoma, Kentucky and Arizona, where teachers were widely perceived as victims of conservative Republican machinations.

In Kentucky, Republican Gov. Matt Bevin said that striking teachers would be responsible for unsupervised children being sexually assaulted, ingesting poison and beginning to use illegal drugs. He also accused teachers of being stupid and selfish in fighting for higher pay and against cuts to their underfunded pensions.

It turned out that many Kentuckians identified with teachers.

Teachers in Kentucky and elsewhere were able to take their issues directly to the state Capitol — the source of funding — and, in the eyes of many, the source of blame for budget shortfalls that caused suffering for teachers and students alike.

In conservative places, teachers were successfully fighting for liberal values. And laws against strikes turned out not to matter so much. Teachers enjoyed such strong public support that authorities did not dare enforce the laws.

How is the L.A. strike different?

An us-versus-them construct does not translate readily to California, where unions are among the state’s most powerful special interests.

And L.A. teachers must face off against a district whose leaders, including Supt. Austin Beutner, echo their union’s demand for increased state and federal funding for schools.

Union President Alex Caputo-Pearl and other union leaders are trying to put forward a complex argument on funding. While they argue that the state needs to do much more, they also says that L.A. Unified is hoarding a fortune — and that district leadership is choosing to starve its schools.

Meanwhile, financial experts brought in by L.A. Unified have reached different conclusions — supporting the district’s assertion that it faces potential insolvency in two to three years, even without meeting most union demands.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.