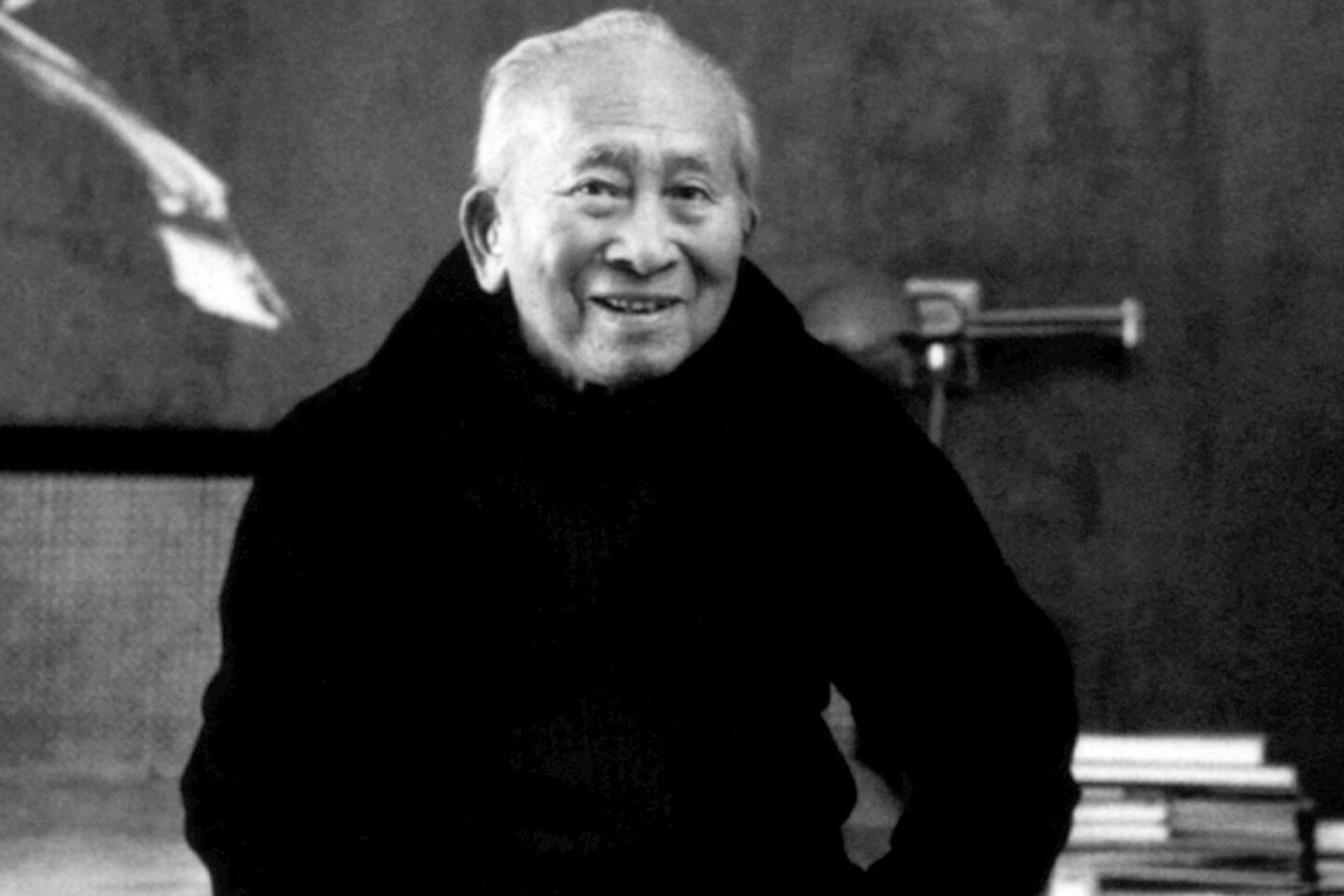

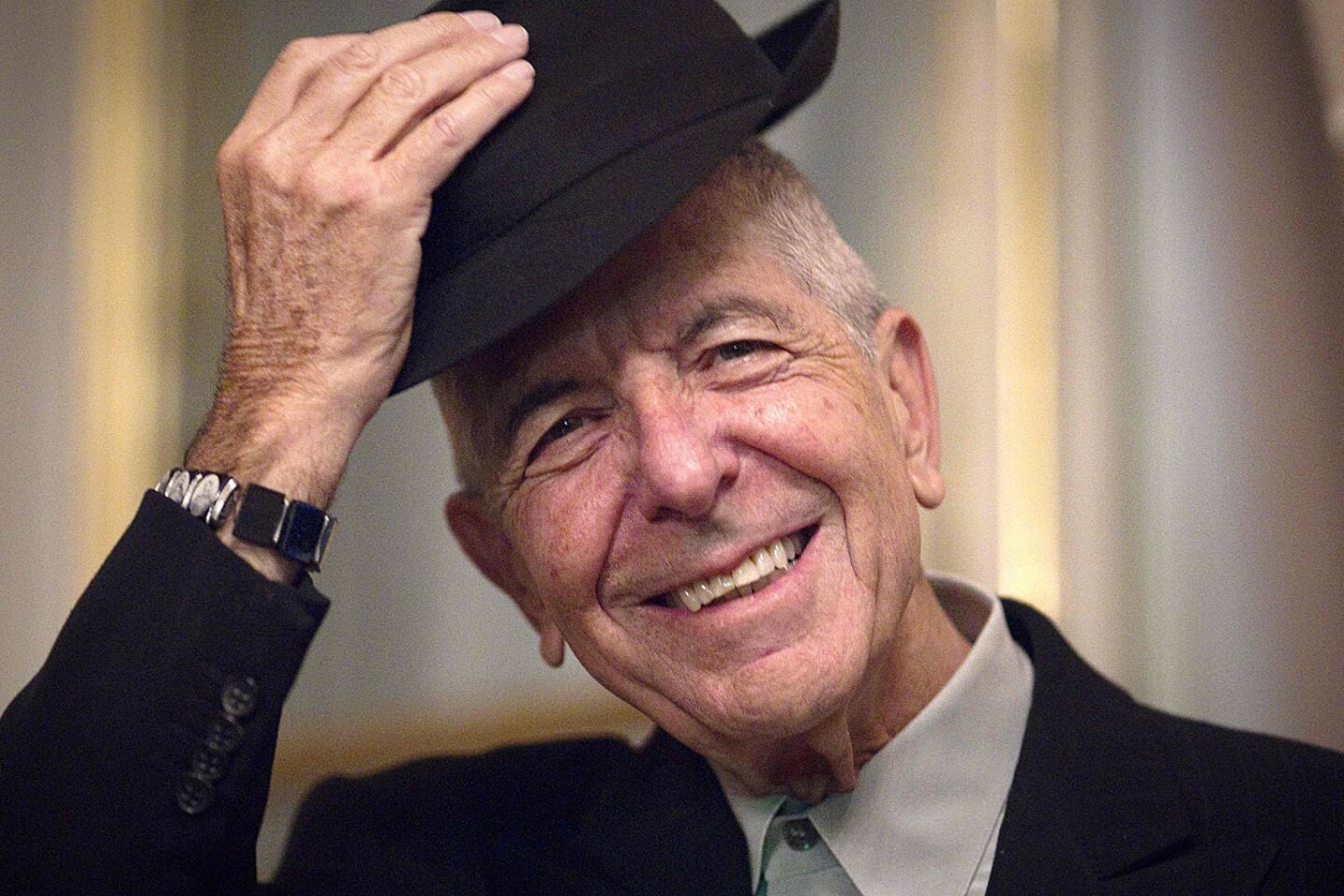

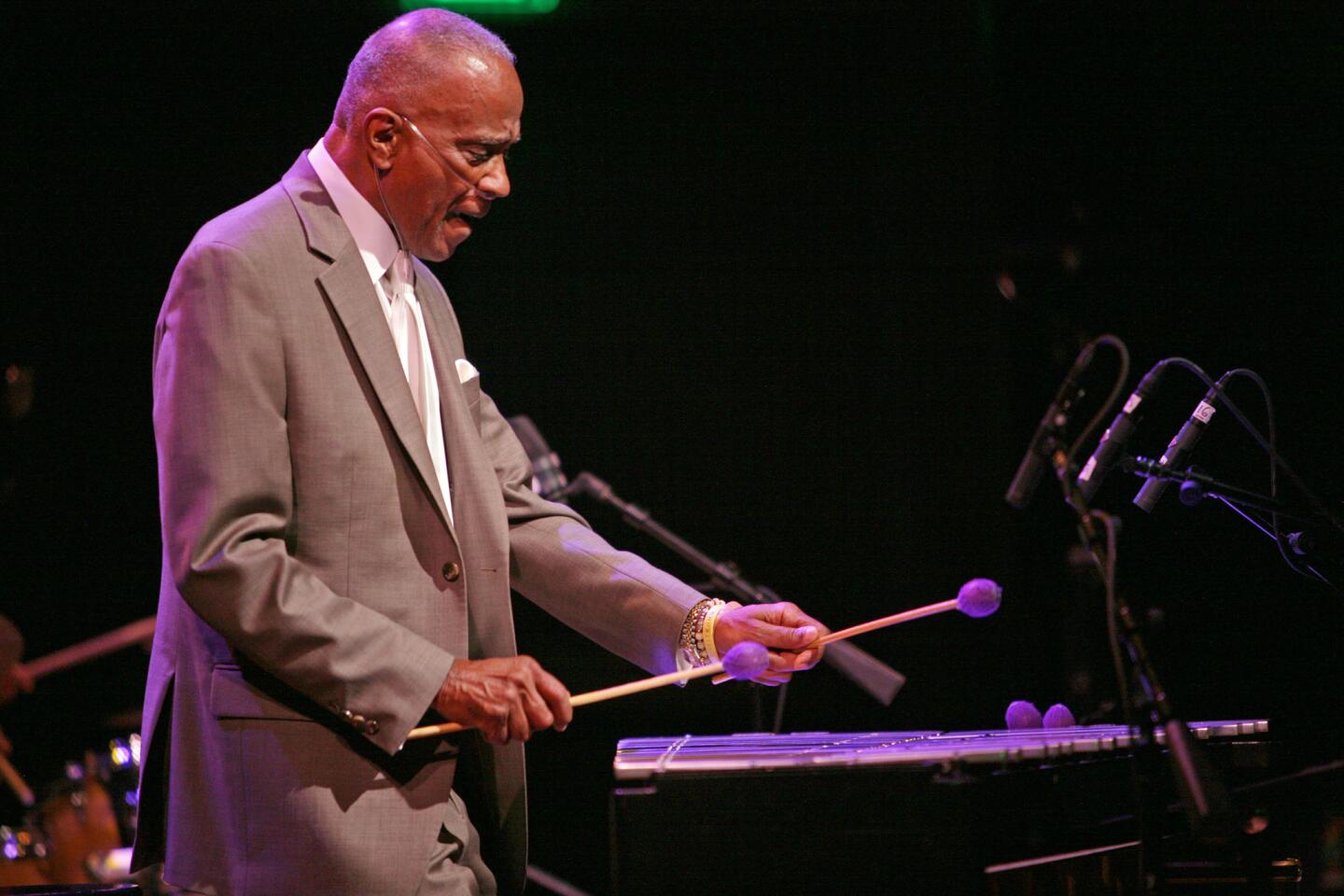

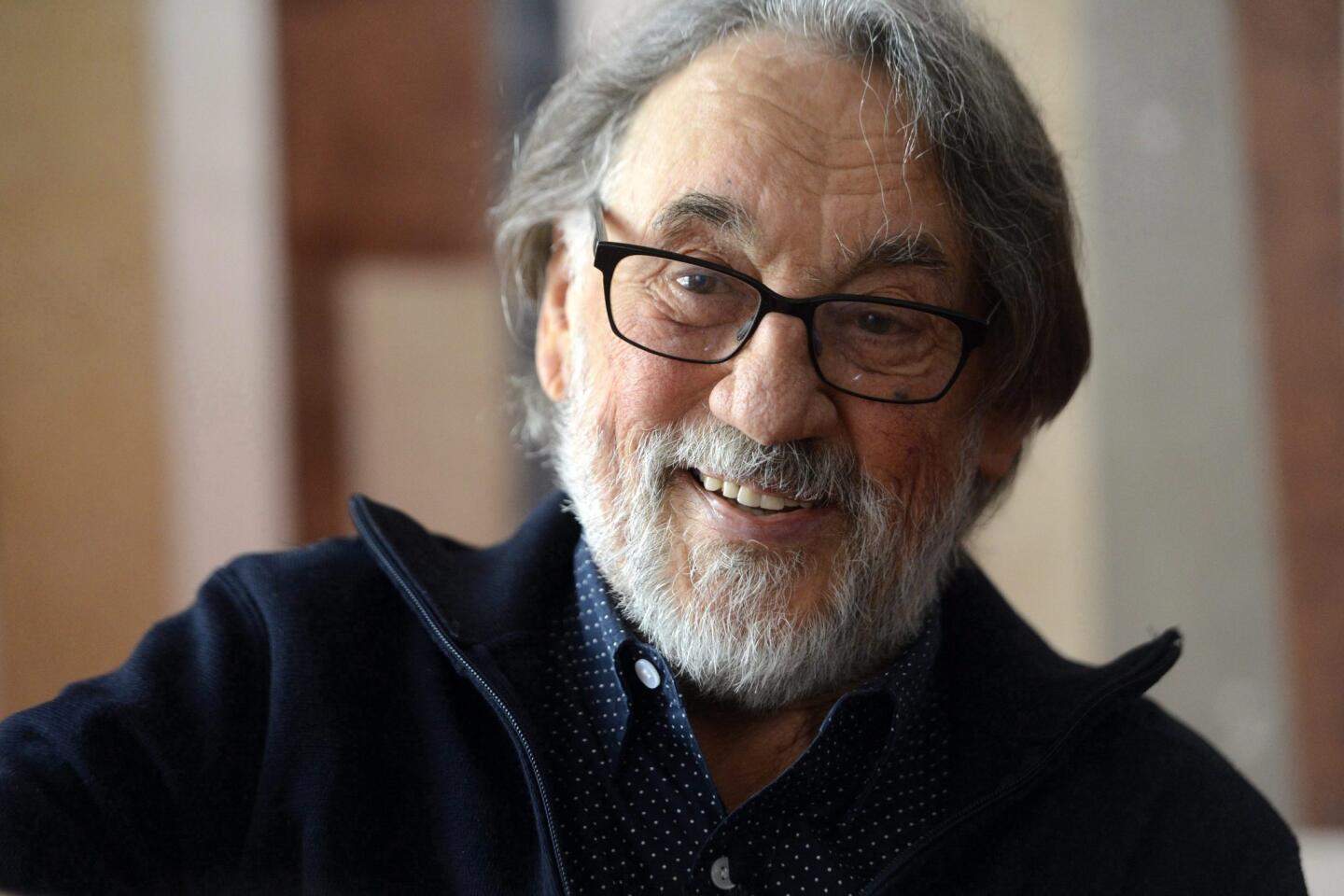

From the Archives: The ballad of Juan Gabriel

Superstar Mexican singer-songwriter Juan Gabriel died Sunday at his home in California at age 66. Here is a 1999 profile from The Times:

First, who he is: the highest-paid Spanish-language singer on Earth. Where he lives: among a dozen mansions and ranches across the Americas--but mostly on a rose-filled estate in Malibu. Age: middle. Style of music: gigantic ballads. Years performing: 28. Number of records sold: 35 million.

Now, who he is not: Julio Iglesias, the Latin pop singer best known to English-language fans.

Yes, the actual king of Latin pop is Juan Gabriel--a debonair multimillionaire who is the ultimate superstar to the half of this city that listens to Spanish radio, and a man occasionally mistreated by the half that does not.

For instance, a West Hollywood antique store owner panicked recently when Gabriel and his manager came in, intending to drop a big--and we mean big--wad of cash.

As Gabriel’s manager tells it, the owner saw Mexicans (God forbid!) and requested they leave the store. Gabriel, who grew up in a Juarez, Mexico, orphanage, did not waste time explaining to her that he could probably buy the entire block. He just left graciously, he says, and spent his money elsewhere.

The store owner can surely be faulted for her prejudice, but maybe not for her ignorance of Gabriel’s fame. After all, Gabriel remains a fiercely patriotic Mexican, even if he does pay a lot of taxes in the United States. And in spite of persistent pleading by his record company, he remains utterly uninterested in “going gringo” despite the added millions that a crossover smash would mean.

That’s not to say that he’s not open to change--but his way.

At 48, Gabriel is changing, in more ways than one. His last album, “Juan Gabriel Con La Banda El Recodo,” was a collection of upbeat banda dance music--with its crashing cymbals, oomping tuba and thumping bass drum a far cry from the sweeping romantic ballads that have been his trademark. It’s part of an exploration of newer Mexican musical forms that reflects Gabriel’s personal growth as well as an effort to connect with a younger audience.

Though Gabriel is working on a duet album with Jose Jose, he is also preparing an album of norteno music, the raucous border music that is a cousin to the tejano style made famous by Selena and her murder.

Gabriel says he’s immersing himself in these festive musical forms because he’s at a point in his life where he’s finally allowing himself to have fun, be silly and, he says, enjoy a childhood he never had. And as the proud father of four children, ranging in age from 7 to 11, he says he is learning through the joy of his own kids how to be carefree--a luxury he, an orphan at the age of 4, was never afforded. This “adult childhood” he says, is fueling his musical growth.

While the happy flavor of his new works may come as a pleasant surprise to his fans, Gabriel says his changes are limited to the Mexican musical spectrum; even though his record company would like--no, love--to see him record a crossover album in English, Gabriel says he will never do that.

“American music has infiltrated the entire world enough as it is,” he says. “Mexican music must be defended, with vigilance. . . . My thoughts, my feelings, my spirit, they are all in Spanish. [My] record company has done nothing for me. They haven’t hurt me, but they haven’t helped me, either. They benefit from my talent and hard work. I don’t need them. It’s the other way around. And my contract with them is in Spanish. ... They say fame is important, and that maintaining your fame is even more important. But to me the most important thing is to deserve the respect of your fans.”

*

Gabriel has sold out 39 consecutive concerts at the 6,200-seat Universal Amphitheatre--three a year for 13 years--which gives him the record for sold-out concerts there by a Latin artist. The legendary Vicente Fernandez is a distant second, with 15 straight sellouts.

But Gabriel’s status as this city’s most secret superstar is apparent when he strolls into Malibu’s exclusive Geoffrey’s restaurant for dinner and an interview. The hostess hardly gives him a second glance. The distracted waiter takes too long serving Gabriel’s Coca-Cola without ice and sloshes it on the table.

But the Mexican busboy?

He drops his tray and his jaw, then runs to the kitchen to tell his friends: Mexico’s patrimony (as Gabriel calls himself) is there, on the patio, eating a light pasta with vegetables. (Gabriel is a vegetarian, because he loves animals.)

The Italian tourists notice too. They have just seen Gabriel on European TV and beg for an autograph. Gabriel--with a classic toss of his head and a sweet, “Pues si, mi amor” (well, yes, my love)--obliges.

Wearing a simple, elegant black silk suit with a Chinese collar, and without his usual makeup and pompadour, Gabriel is so relaxed, so suntanned and so downright playful that it is easy to forget his status as the most-played Spanish voice on Los Angeles radio.

Gabriel has just driven himself here from the airport, where his flight from Miami landed late. “I’ve been circling,” he says, drawing a ring in the air with one graceful finger to convey his frustration.

Even though Gabriel dislikes flying (and interviews), he is unfailingly polite. He has not chosen this restaurant; a Versace-loving publicist from BMG, his label, has.

“When I’m in town, I never go out,” Gabriel explains. “I’m the kind of person who prefers to stay home.”

Gabriel removes his tinted glasses and hangs them through his buttonhole. Gesturing to the vines growing on the patio’s trellises, he nods appreciatively and says, “This is very nice, eh?”

Seemingly comfortable, he even compliments his interviewer, and jokes, “Mija, hablemos de novios.” (Honey, let’s talk boyfriends.)

It’s a gutsy tease. Gabriel probably knows that the question of his sexual identity is on his interviewer’s mind. According to his manager, Gabriel’s sexual preference is always of interest to prying American reporters.

An unabashedly effeminate man who has never been married, Gabriel is rumored among his fans to be gay. He has hinted over the years that they could be right, and his flowing capes, scarves and makeup do nothing to silence the talk. His publicist says his children, while biologically his, were conceived through artificial insemination. (Gabriel gave their mother’s name only as “Laura” and described her as his best friend.)

In this regard, Gabriel has done what might seem like the impossible: He has been accepted and adored by an often violently homophobic culture, in spite of what one fan called “the obvious.”

Several other stars have been accepted in Latino circles despite ambiguous sexuality, including television astrologer Walter Mercado and Cuban singer Albita. Scholars specializing in Latino culture and sexual norms attribute this acceptance to a Latino tradition of “don’t ask, don’t tell,” whereby a beloved family member--or celebrity--is “allowed” to be homosexual, as long as they don’t say so.

There is some evidence that this is happening with Gabriel. At a recent concert in Pico Rivera, where he gave his first all-banda performance, a grizzled older gentleman who described himself as a huge Gabriel fan spoke loudly about Gabriel’s music and talent, and then whispered, “We know what he is. You know what I’m talking about? He doesn’t have to say it. We don’t care. But we would never want him to talk about it. We respect him because he doesn’t.”

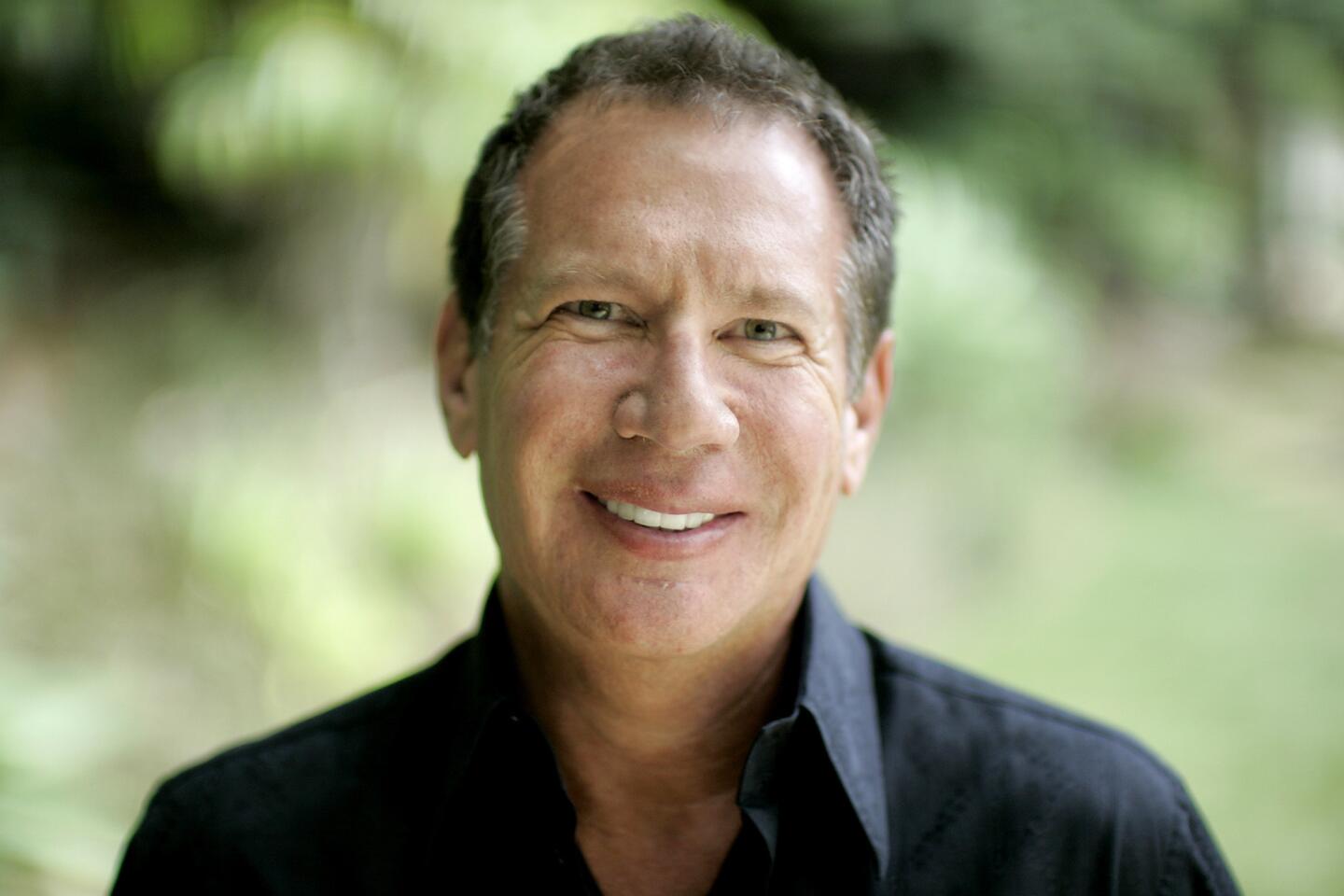

What Gabriel may or may not do in his private love life “does not matter” to his fans, according to Ralph Hauser, Gabriel’s longtime friend and manager. Says Hauser, “Who he is as an artist and a human being has always transcended everything else.”

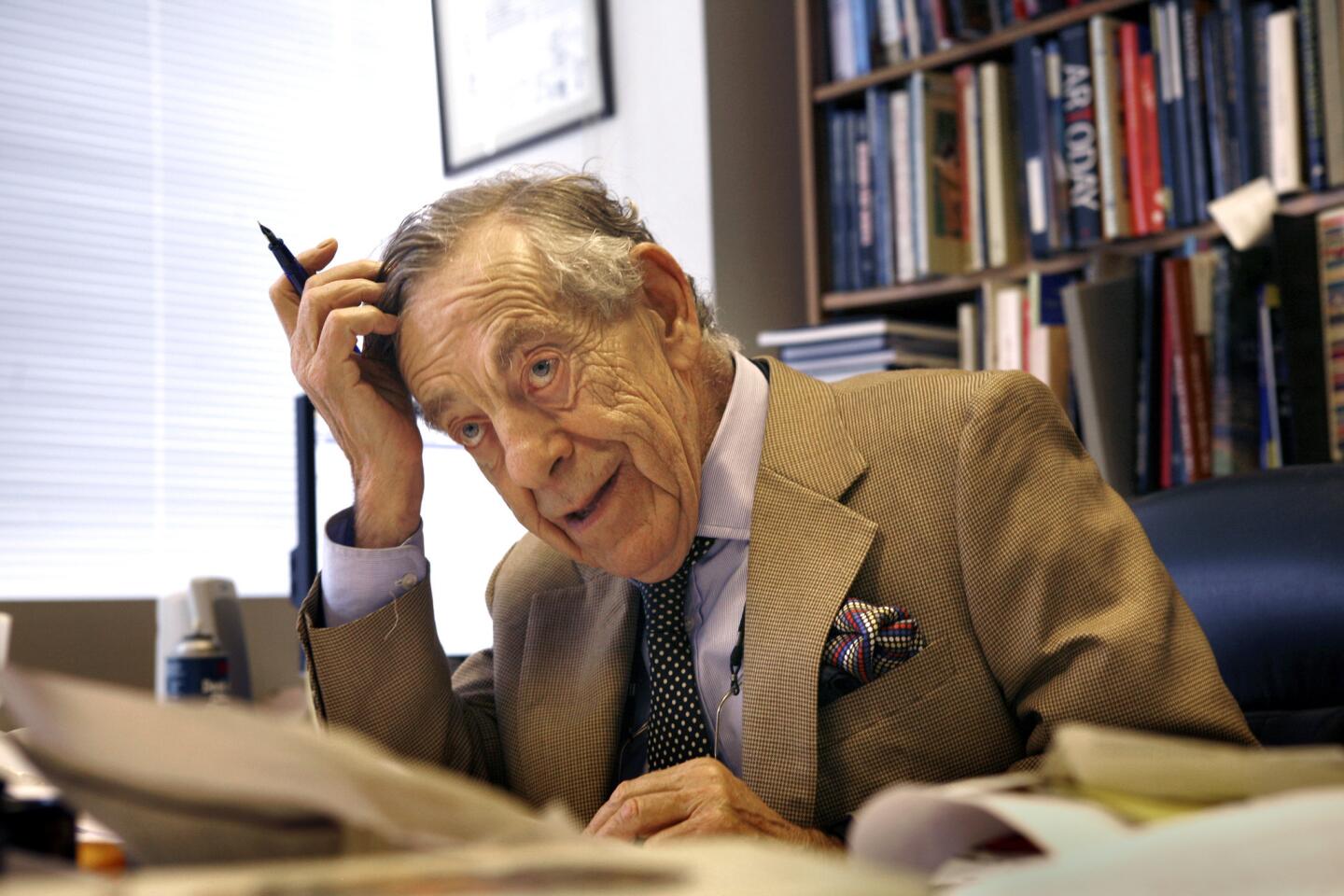

Jose Z. Garcia, director of the Latin American studies program at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, has watched “the Juan Gabriel phenomenon” with great interest as a cultural critic.

“Here is a man who was not only poor, but orphaned,” Garcia says. “It’s a Cantinflas-type of stereotypical background, which may in some ways work in his favor now. But also you have a man whose sexual orientation is somewhat disparaged.

“Against those odds, he’s made it. In some ways all of this has now become the icon of who he is. It’s almost to the point now where there’s a conspiracy with his audience, sort of that we’ve been together this long time, we know who each other are, we admire ourselves for admiring you, and we know that you love us.

“It’s a postmodern mirror thing, in that we see ourselves in your music. And we see the best of ourselves in us when we give you a standing ovation; it’s proof that we aren’t prejudiced.”

*

Part of the appeal of Juan Gabriel, the human being, is his rags-to-riches life story.

Fans say he has struggled just as they have, and again and again point to the positive messages about hard work, forgiveness, family and self-esteem in his autobiographical lyrics.

Gabriel was born Alberto Aguilera Valadez, the youngest of 10 children born to Gabriel Aguilera Rodriguez and Victoria Valadez Ojas, two peasants from Paracuaro, Michoacan, Mexico. Alberto’s father died in a fire shortly after his son’s birth; years later, the son would take the father’s name as his stage name. His closest friends still call him Alberto.

Valadez fled town after running into problems with her in-laws and took work as a servant in Juarez. Unable to feed Alberto and the other children on her meager wages, she gave Alberto to an orphanage when he was 4.

Gabriel says his first memory in life is of her leaving him there. “You don’t know the word for ‘abandon’ at that age,” says Gabriel. “But you know what is happening. You know you want to be with your mother, and she is not there.”

Alberto spent eight years at the orphanage and saw his mother about once a year. He found surrogate parents in Micaela Alvarado, the institution’s director, and in Juan Contreras, a teacher there. The “Juan” in Juan Gabriel is a tribute to Contreras, who eventually invited Alberto to live with him, teaching him to make wooden trinkets and sell them on the street.

When Alberto was 14, he left Contreras’ home to find his mother, and then dedicated himself full time to selling food on the street to help support the family.

For fun, he wrote songs in his head and sang them as he worked. (A song he wrote at the age of 13, “La Muerte del Palomo,” about his father’s death, became a smash hit years later.)

One afternoon, as Alberto was selling tortillas on the street, his singing caught the attention of two sisters, Leonor and Beatriz Berumen, who, feeling sorry for him, invited Alberto to live with them so they could teach him to read the Bible and nurture his singing.

As he became involved with the Berumens’ church, young Alberto had a chance to travel to a sister church in Lake Elsinore, where he stayed for a time with an African American family.

“That’s where I was first exposed to African American music,” Gabriel said. “And I knew then that if there was a God, and if God was listening, he was listening to African American music.”

After a year in California, Alberto returned to Juarez, where a TV music show host was impressed with the big-voiced 16-year-old, and gave him his first stage name: Adan Luna.

Around this time, “Adan” began singing in local bars, including one called El Noa Noa, which he would make famous in song and film. By 19, the determined young singer had taken himself to Mexico City and sparked enough interest in his powerful voice to get his first recording contract, under his new stage name, Juan Gabriel. Within a year, he had a gold record, “No Tengo Dinero” (I’ve Got No Money).

The first major purchase Gabriel made with his new income was a house for his mother in Juarez in 1971; at the time, he paid what would have been $250,000 in the U.S. She lived for only three more years.

To explain his devotion to the woman who had abandoned him, Gabriel says, “Mexico is a very mom-centered culture. You’ll find stores open on Father’s Day, but never on Mother’s Day. For us, mothers are very important. I know she did the best she could, given what she knew.”

After his mother’s death, the owners of the house where his mother had been employed needed someone to buy the home, where Gabriel said his mother had been humiliated and treated like a slave. Gabriel stepped in.

“It was quite a scandal,” he says, smiling devilishly.

In addition to that house, Gabriel later bought a house in Juarez his mother had told him was her dream house. Eventually, the orphanage even came up for sale. Gabriel bought that too and turned it into a music school.

He bought a nicer building elsewhere in the city in 1987 and built a new orphanage, Semjase, home to 100 children. In addition to being an orphanage for boys, Semjase, named for Gabriel’s goddess of music, is also a music school for city children. The facility is a large house, renovated and filled with music rooms, recreation rooms with video games, and surrounded by gardens and apple trees. In all, Semjase has about 50 full-time employees; their salaries are all paid out of Gabriel’s pocket.

“We are very aware that apart from his music, Mr. Juan Gabriel is completely dedicated to children,” said Semjase director Luz Alicia Perez Gallegos. As she spoke, the blare of a young brass band practicing on a patio cut through. According to Perez, Gabriel’s philosophy is that children needing affection will find joy in music.

Perez says Gabriel is beloved in Juarez. “He’s a kind human being. He took a very difficult period in his life and turned it into something beautiful. He is the only singer I can think of who is doing something like this, completely from the goodness of his heart.”

*

Houses remain a passion for Gabriel, who owns ranches in New Mexico, Texas and Mexico and also mansions in Florida, Texas, Juarez, Cancun and elsewhere.

“Houses are an investment to me,” he says, finishing his dinner at Geoffrey’s. “It’s not that I have something to prove anymore. I did that when I was younger. I buy them so that my children will have some security when they grow up.”

Maria Nava, program director for La Nueva FM 101.9, has been a close friend of Gabriel for more than 10 years, and says that the most amazing thing about him is his parenting.

Nava said Gabriel plans surprise parties for his children on holidays and dotes on them, even writes them songs and sings to them. “His best compositions have never been recorded,” Nava said. “Because he writes his best songs for his kids’ ears only.”

Though Gabriel enjoys gardening, he does not have much time to tend to his gardens himself. He performs an average of once a week and travels often. Hauser says that “you see the same fans in Los Angeles and Chicago. They’re like the Grateful Dead fans. They follow him everywhere he goes.”

To relax, Gabriel says, he writes songs. His compulsive songwriting has made him Mexico’s most prolific living songwriter. He says he is “one of those lucky people whose work and fun are not distinct.”

“I don’t make plans,” he says. “I don’t follow a schedule every day. I live in the moment and let inspiration come to me. To me, music is mankind’s way of thanking the universe for letting us be here.

“For some, it’s a way to thank God. For others, it’s a way to thank nature. It is universal. And to make it, you have to be fully alive. I do my best to do that. I enjoy every moment, because I believe that once we die, that’s it. We’re not coming back. Lovers come back. Styles come back. But time? It never comes back.”

Some of Gabriel’s most enthusiastic fans are rival artists, including Luis Miguel and Marc Anthony. Anthony credits his entire salsa career to Gabriel’s composition “Hasta Que Te Conoci,” a remake of which became Anthony’s first hit.

“Juan Gabriel has changed the face of music,” Anthony said from Puerto Rico. “His music has transcended generations and genres because of his simple, timeless melodies. Add a little tear and a great voice and you have Juan Gabriel, which is what caught me right off the bat. I’m a huge fan. We’re talking huge!”

Gabriel has also won endless prizes, yet he insists that “the best prize I can think of is when I look out in the audience and see people singing my songs, or when people wish me well or when they say, ‘God bless you.’ ”

And as for money? “If I lost it all tomorrow I wouldn’t care,” he says. There is no hint of sarcasm in his voice, and his eyes are clear and sincere. There is no reason to doubt that he means this.

“Money doesn’t make you a moral person, or a good person, and neither does religion,” he says.

The waiter returns, to take desert orders.

“Do you have chocolate ice cream?” Gabriel asks.

The waiter manages a tight smile and says, “No, I’m sorry.” He rattles off the names of more complex after-dinner fare. Gabriel, unimpressed with the pretentious pastries, skips dessert.

“Money can be taken away from you, by the IRS or by pistol,” he continues. “That’s why I always measure riches in terms of wisdom. No one can ever take from you what you know.”

*

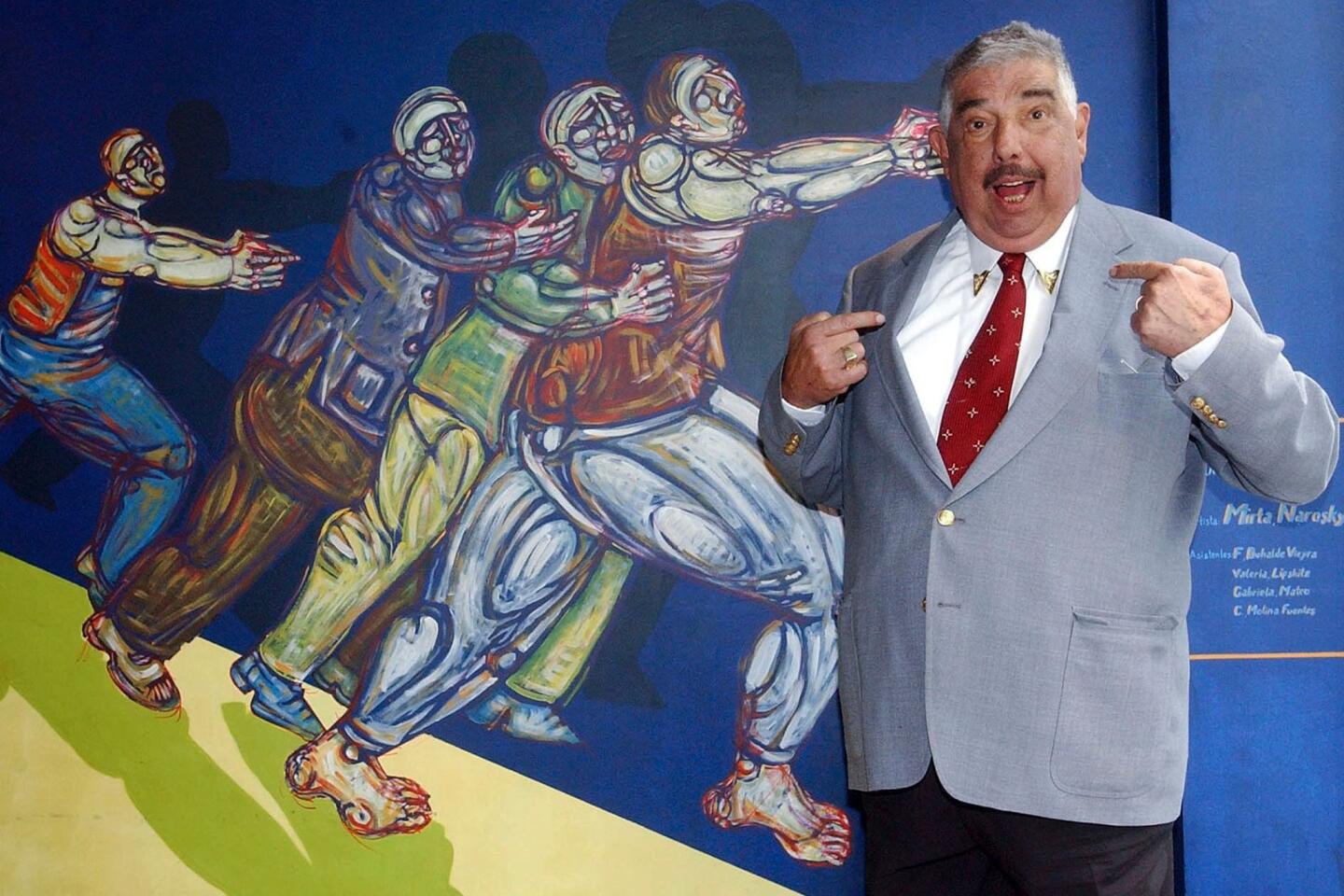

On the day after the restaurant interview, Gabriel rides in the back of his white limo to the Pico Rivera Sports Arena, where he gives two Valentine’s Day shows, performing banda music from his newest album. About 4,000 fans fill the arena for each show.

Playing at this arena is, for Mexican musicians, a little like playing the Grand Ole Opry for country musicians. Before Gabriel’s sets, cowboys perform tricks on horseback in the mud of the rodeo arena. Families sit on bleachers in their jeans and cowboy hats, eating popcorn and drinking soda or beer.

By performing banda at the Pico, Gabriel proved that no matter how many millions he is worth, no matter how many orchestras he’s played before, he is still in touch with regular people. The banda tunes are very different from Gabriel’s usual repertoire of ballads, and his enthusiasm for the festive new music prompts him to dance and laugh.

Wearing shiny black patent-leather boots and a luxuriously flowing red and black Valentine’s cape, Gabriel ignores the stage set up on one side of the arena, preferring to get down in the mud. A small round table with a white linen tablecloth, topped with a crystal vase holding two long-stemmed red roses, waits to one side, near bales of hay.

Without a second thought to his expensive shoes, Gabriel paces the Pico as he sings, stopping at intervals to hold eye contact with a fan, blowing kisses as he goes.

One woman hurls herself like a stunt double from the bleachers onto the stage and then flings her body into the mud next to Gabriel. He continues to sing, chuckling beneath the notes, and helps her to her feet. He appears genuinely touched, and surprised.

“Ay, mi amor,” he says as she stands, giving her a you-should-know-better look and a kiss on the cheek. “Ten cuidado, mi’ja.” (Be careful, sweetheart.)

Security comes, and one more Juan Gabriel fan is led away, flushed from coming into contact with him.

Down in the mud, the man who could be Julio sings on.

ALSO

Here’s why L.A. won’t give you a permit for that ‘granny flat’

Framed, Chapter 1: She was the PTA mom everyone knew. Who would want to harm her?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.