State water board demands more water for fish

In an unprecedented step, state regulators Wednesday adopted standards that would force San Francisco and several big San Joaquin Valley irrigation districts to give some of their river supplies back to the environment.

But they also left the door open to agreements that would significantly undercut those flow requirements — underscoring the winding path that marks any significant change in California water policy.

The vote by the State Water Resources Control Board is by no means the final say on the matter. Settlement discussions will continue next year. And water users have vowed to challenge the flow mandates in court.

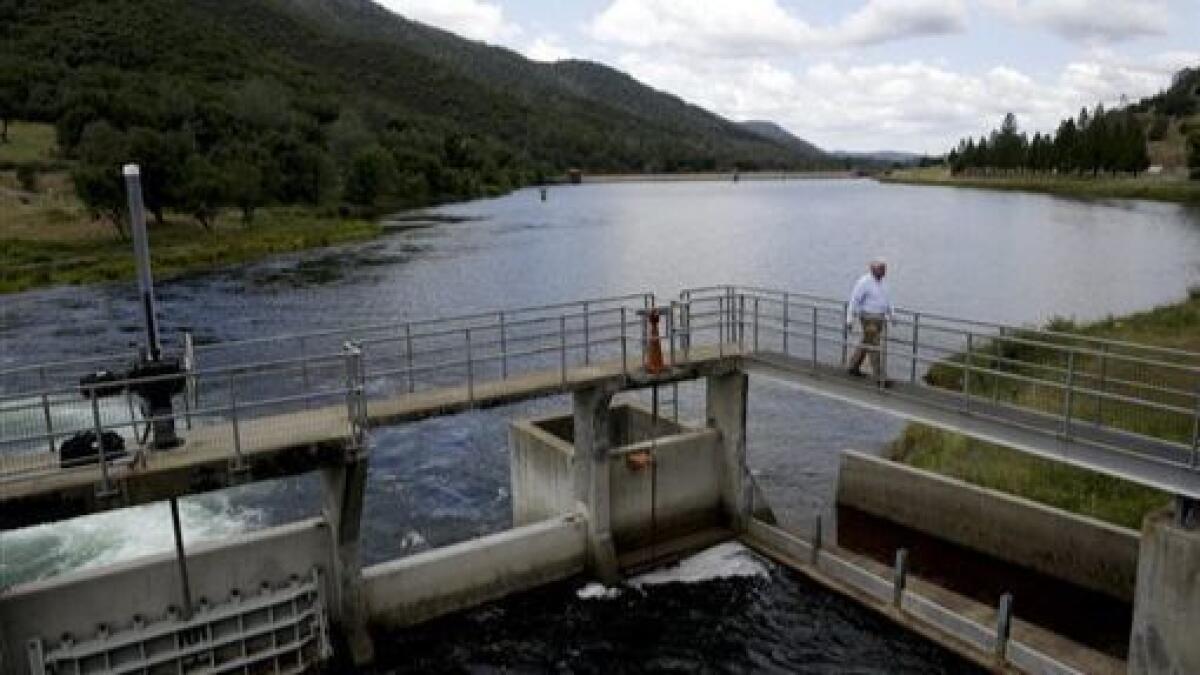

Under the new requirements, water districts would have to reduce their historic diversions from three salmon-bearing rivers, the Stanislaus, Tuolumne and Merced. Average flows on the three tributaries of the San Joaquin River now range from 21% to 40% of what they would be without dams and diversions. At times the river beds hold as little as 10% of the natural flow.

Not only would greater river flows improve conditions for struggling salmon populations, they would ultimately boost needed inflow to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the ecologically ailing center of California’s water system.

Many of the water users have diversion rights that date back a century or more. They have fiercely criticized the board plan, which would collectively cost them 300,000 acre feet of supply — or roughly 15% of their total diversions on all three tributaries.

Irrigation districts argued Wednesday that if the board adopted the flow requirements, it would start a years-long legal war and hinder progress in improving environmental conditions in the delta watershed.

They urged the board instead to give them more time to forge settlements with state water and fish and wildlife agencies.

Officials with those departments have spent the last month in intense negotiations, trying to strike accords — which the state board has encouraged but cannot take part in.

California Fish and Wildlife Director Chuck Bonham told board members an agreement had been reached on the Tuolumne River, but not on the Stanislaus and Merced rivers.

Bonham and Department of Water Resources Director Karla Nemeth supported voluntary agreements as the best way to quickly achieve environmental improvements.

They presented the outlines of a settlement framework for the entire delta watershed, including the Sacramento River Basin, which is next in line for new flow standards.

Under their proposed agreements, water districts would make habitat improvements, such as expanding floodplains and building up spawning beds with gravel.

They would also boost fish flows — but to a lesser degree than mandated by the board. Farmers would fallow land to free up irrigation supplies.

Over a 15-year-period, the state would contribute $900 million and water users, $800 million, to a fund to pay for habitat improvements and water purchases for the environment.

The proposed framework would “make things actually happen in a timely way,” said Nemeth, who called it a historic collaboration.

But environmentalists — who have criticized the board’s standards as too weak — condemned the proposed settlement terms as wholly inadequate.

“The settlement is less than half of what the water board asked for,” said Doug Obegi, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“Without any protections for the delta itself and a proposal that the public would pay for a lot of the water, it looks like the state’s strategy has been to ask for less to get to yes,” he added.

The board vote caps years of discussions and staff work on a long overdue update of water quality standards for the delta.

Regulators have until now principally focused on the harmful environmental effects of the delta’s pumping operations that send water south and have helped push native delta smelt and salmon to the brink of extinction.

The tributary flow standards extend the onus of meeting delta protections to upstream diverters who have long escaped responsibility for the delta’s ecological woes, despite their massive withdrawals from the river systems that feed the delta.

“I think the time to act is now,” board Chairwoman Felicia Marcus said when the five-member panel voted — with one “nay” from member Dorene D’Adamo — to adopt the plan at the end of a 10-hour hearing.

At the same time, Marcus encouraged water users to continue settlement talks. And she noted that it would take more work to implement the standards in the form of regulations.

“This is one step.… I do think today is an important day in the spirit of moving forward. We have a lot more work to do.”

Commercial salmon fishing groups, which have suffered closed seasons and declining catches, praised the board action.

“Today’s vote represents the setting of the bar, and water users will either rise to meet it or get beaten in court,” Noah Oppenheim, executive director of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations, said in a statement.

Twitter: @boxall

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.