A look behind the Hollister Ranch gates. Will the public ever access these exclusive beaches?

Drone flyover at one of the most pristine stretches of coastline in California —Hollister Ranch.

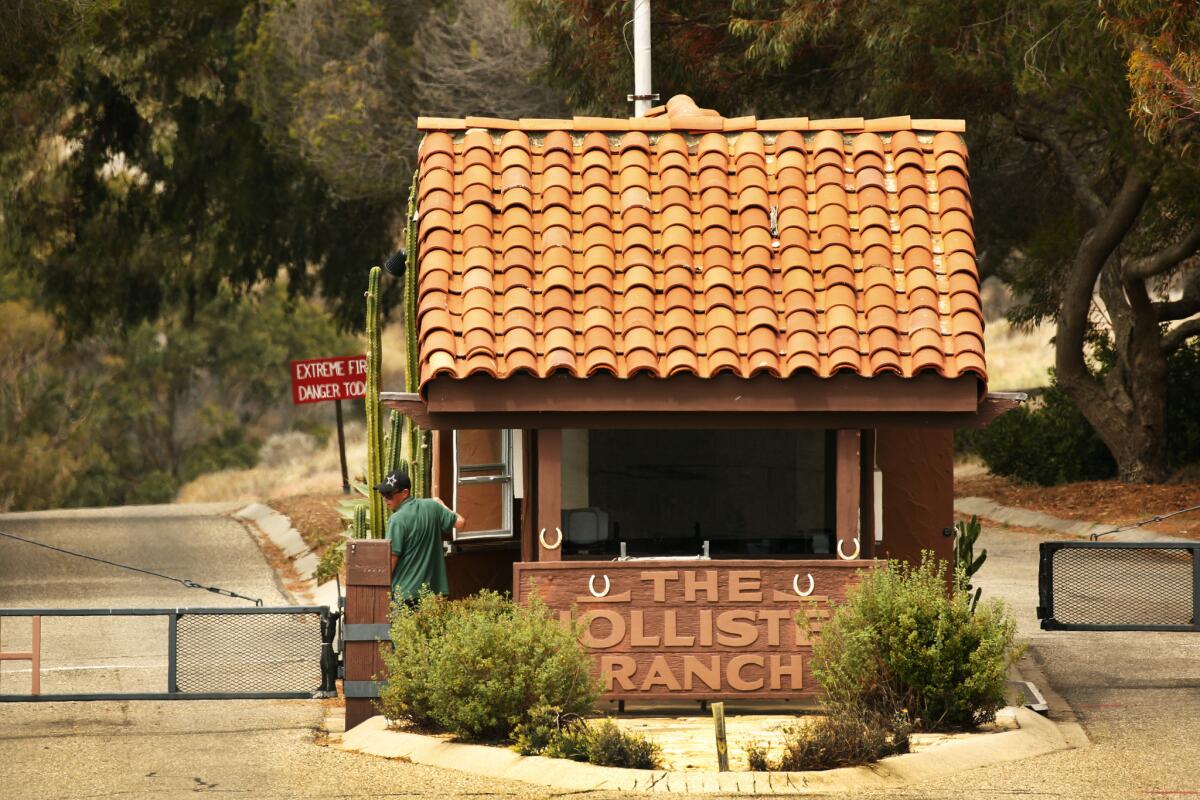

Tucked off a turn on Highway 101, down an unmarked fork in the road, the elusive gates of Hollister Ranch swung open to a 14,500-acre oasis — described by many as the last vestige of the old California coast.

Andy Mills waved to the guard and, familiar with every bump and turn, navigated his truck around the ranch’s first narrow curve. He braked for a cow that ambled across the pavement. Three more grazed nearby.

“These fellas have the right of way around here,” said Mills, who lives and works on the ranch. “This place is really quite something.”

Here along the rolling hills west of Santa Barbara, where willows line the creek and cattle roam free, the verdant land unfurls to reveal a rugged coastline largely unspoiled by man. Few have stepped their toes in this sand, but those who have say it evokes a feeling so vast — even spiritual — that it must be experienced to be understood.

Thus the dilemma: The beaches abutting Hollister Ranch are special because they are so pristine. They are pristine because of the ranch’s history of being so exclusive. Excluding the public, however, goes against the tenet that California’s beaches belong to everyone.

Owners have been on the defensive in the months since they reached a controversial deal with the state Coastal Commission that essentially capped the number of people — and type of people — who could visit these coveted beaches. Advocates have gone to court, and state officials are now vowing to find a way to open a public route through the ranch to the sea.

The stakes are high, the outcome now emblematic of access across all California beaches. But Mills and fellow residents fear the loss of this treasured land — and way of life — that they’ve fought for decades to protect.

Can having both access and preservation, some wonder, be possible at a place like Hollister?

The story of this land begins with the Chumash, whose villages flourished among these ancient oak groves and canyons 35 miles west of Santa Barbara. Then came the Spaniards and after that, the Yankees.

By 1853, Colonel W.W. Hollister — born in Ohio, where he attended Kenyon College — had come west to the newly American California. He struck a few deals and eventually settled along the Gaviota coast, where his family ran a cattle operation for more than a century.

After Hollister’s son died in 1961, there was talk about building planned communities — even creating artificial lakes — throughout the ranch. But the developer went bankrupt, and the mortgage company instead held a design competition.

In came a Texas cattleman by the name Dick LaRue. He proposed preserving Hollister as a historic ranch — subdividing the land into 100-some-acre parcels but allowing only 2% of each parcel to be developed.

Two acres for your home and barn; 98 for the cattle, he declared. No fencing, no mansions. Low density would be the selling point.

Surfers cobbled together paychecks, lured by Hollister’s famous surf breaks. Others chipped in for their slice of this untarnished paradise. Today, many roads remain unpaved, cell service is spotty, water is shared from a number of wells.

Any construction must blend into the environment. Owners are limited to 12 guests per parcel per day. Not part of the plan was the general public, who technically own — and have rights to access — the beach under California law. For decades, the ranch fought back attempts to open the coast to the general public. Access today is still on their terms.

The ranch “represents a concept of land development that is a model for both landowners and environmentalists,” according to a history book by the Hollister Ranch Conservancy. “Given time, money and human sensitivity… the integrity of a magnificent piece of land such as the Hollister Ranch can remain intact.”

Standing at the top of a ridge overlooking Cuarta Canyon, Beverly Boise-Cossart marveled at how a few weeks of rain had transformed the lush landscape. The sky that day was particularly clear — miles away, Point Conception poked through as a knob of land. A hawk flew overhead.

Reaching this vista required veering up onto a dusty, unpaved road that is often unpassable during the winter except by horse. Boise-Cossart loves this spot.

She squinted into the distance, first pointing to a coyote sprinting across the terrain, then to a white dot nestled into the curve of a different ridge — the only house visible from this vantage point.

“This is what 50 years of residential development looks like here,” said Boise-Cossart, who struggles with the growing debates over access.

“Do we want access at all costs?” she said. “Once we lose this, we can’t go back. We can’t restore a place like this.”

Her neighbors today include filmmaker James Cameron, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard and musician Jackson Browne. More than 1,000 people now own a share of the ranch.

A timeshare to a cabin today goes for almost $1 million. A full parcel with a home was recently listed for more than $17 million.

“Watch mega-pods of dolphins and the annual grey whale migration from the south-facing windows,” the listing said. “Ownership of this property allows you access to 8.5 miles of sandy private beach frontage.”

Many residents, now under intense public scrutiny, have objected to their characterization as rich landowners who just want a private beach.

“We’re not all wealthy here, but the ranch is the most important thing to us,” Boise-Cossart said. “People will give up everything else to pay their assessments, to stay here. This is the core meaning of their lives.”

When Boise-Cossart first moved to the ranch in 1977, she worked three days each week as ranch secretary, two days in construction. In the winter, she often trekked two miles in the mud to work.

Her husband, a carpenter, artist and surfer, also bought into the ranch in the early years — scraping together a $3,000 down payment for his share of a parcel. For four years, he lived in his van to pay off the rest.

Over the decades, they’ve worked on the ranch and for the ranch, serving on various boards. They’ve raised children on this land, celebrated marriage, even said goodbye to loved ones. Recently, they welcomed the birth of a granddaughter.

Today, Boise-Cossart volunteers as the president of the ranch’s cattle cooperative.

She pulled over one recent afternoon to catch up with Kathi Carlson, one of two cowgirls overseeing the cattle. Carlson had just spent the morning on horse shepherding some 300 cows with calves, as well as 650 stockers, out from the back hills.

Hollister is divided into 136 parcels, but Carlson sees the entire ranch as one giant pasture. She recognizes many cows by face and knows which babies are with which moms. If a cow is having trouble giving birth in the middle of the night, she’s the first to saddle up.

“It's like you have a really, really big house, and you've just got to keep it organized. You’ve got this set of cow-calves here, the stockers here, the yearlings there,” said Carlson, who fell in love with the ranch, left her job as a graphic designer for Patagonia in 2004 and has been working with cattle ever since. “They get mixed up all the time and... you've got to straighten it all back again.”

The two women chuckle and trade war stories. That time Boise-Cossart was driving home from a school board meeting, when a calf tripped and fell off an embankment — right onto the hood of her truck. Carlson, caught between a mother cow and baby last year, got her ribs broken.

So how do you put a public trail through a cattle ranch, they wonder? How many people know that an angry mother cow could be more aggressive than a mountain lion? What about the coyotes and wild pigs? And, her eyes widening, what about the bulls?

“We try to put our bulls together so that they fight it out in the small corral first,” Carlson said. “But when they get into a fight over a girl cow, you can't get out of the way fast enough. They'll run into your car, they'll take a fence out, they'll go off a cliff fightin’.”

Who would be responsible, she wonders, if someone from the public got hurt?

And how do you keep visitors from wandering around? People here don’t just go hiking on other people’s parcels, she said. There’s limited fencing, few boundaries, but unspoken rules and respect.

Other ranch owners also worry how unfettered access could change this way of life. Some have pointed to the trashing of Joshua Tree when park rangers were off duty, and the mass trampling of Lake Elsinore during this year’s super bloom.

“One need only to look up and down the coast… pristine natural coasts with endangered species have given way to garbage strewn areas and parking lots,” Grant Fowlie, a ranch owner, wrote to the California Coastal Commission. “Essentially, we would be destroying this small area of beauty to create another couple miles of the same.”

Those on the other side of the gate bristle at this demonization of the public. “Nobody wants to run in and trash Hollister Ranch — we all care about the environment,” said Susan Jordan of the California Coastal Protection Network, who has joined a coalition of trail and environmental justice groups in fighting for more access.

Coastal Commission Chair Dayna Bochco, in a public outburst last year, also pushed back at owners — calling them subtly elitist for worrying about losing such pristine land: “You shouldn’t be able to enjoy it any more than any other human being. You are no better of a steward than we are.”

Logistical challenges are par for the course, she said. Officials have found ways to provide access — while balancing preservation — at Big Sur and other remote, rugged stretches of the coast. At Hollister, paved roads to the beach already exist for owners.

“We would not have spent so much time and so many resources pushing for public access at Hollister if we didn’t think it was possible,” said Bochco, who recently met with owners and toured the ranch. “Fortunately we have decades of experience doing this across 1,271 miles of California coastline, and there is a way to do it here too.”

But the ranch is known for getting things its way. Since the passage of the California Coastal Act in 1976, owners have managed to avoid providing beach access for all.

First, they got an exception carved into the law allowing the ranch to bypass a requirement that each of its many owners provide a public route to the beach when developing their parcels.

Lawyers working for the ranch have been around for decades, finding ways to drag out legal battles in perpetuity. Recent tactics include trying to disqualify the judge who rejected their motions, and petitioning to the state Supreme Court.

But after decades of stops and stalls, state officials are now doubling down on a comprehensive access plan that could include a walking trail, bike path and shuttle to minimize traffic. A state lawmaker is pushing for a 2020 deadline.

Life on the ranch also has not been without controversy. In a 1992 lawsuit filed against the Hollister Ranch Owners Assn., a few residents alleged a culture where board members met secretly to make ranch-wide decisions, played favorites, imposed questionable fees and made life difficult for those who did not abide by their rules.

And critics recently questioned the ranch’s claim to an agricultural tax break, as well as the environmental hypocrisy of driving on the beach. The president of Hollister’s board responded that they had voted in December to “prohibit beach driving, effective immediately.”

Boise-Cossart has heard it all.

“We inherited driving on the beach,” she said. “The Hollisters drove on the beach, and then toward the end of Hollister ownership, they let a certain elite group of surfers, the Santa Barbara Surf Club, come in and drive on the beach. So we still have some owners who are members of the surf club, who insist that it's their God-given right to drive on the beach — and we finally said no.”

As for access, that stance was also inherited from the territorial surf culture, she said. “But I think our attitude about public access has been changing.”

She’s wary of the state’s plan, but would consider managed access like the Arroyo Hondo Preserve. There, guided nature hikes by the Land Trust for Santa Barbara County are offered to the public two weekends a month.

“We feel a real obligation to share this special place,” she said. “But we want to make sure it's done right.”

Out at the ranch’s sprawling tide pool, the sun was setting as Boise-Cossart’s daughter, Elise Cossart-Daly, wrapped up an afternoon of volunteer work.

Cossart-Daly, a civil rights and environmental lawyer, was tasked with expanding the Hollister Ranch Managed Access Program, which hosts tide pool trips for schoolchildren and tours for birders, botanists and researchers.

For years the ranch has also invited disabled veterans and other special-needs groups to visit an uncrowded beach, she said. Under the proposed expansion, the program would serve up to about 400 people a year. The tide pool trip would be offered at least 24 times a year for at least 20 students.

“For me, it's really important to think about who will get access,” she said, tiptoeing barefoot along the rocks as she pointed to barnacles and sand dollars. “How do we balance preservation with ensuring that a wide array of people have access to this place? How do we create meaningful opportunities for these underrepresented groups?”

It’s been empowering to grow up watching her mother make a name for herself on the ranch, she said, and to have the cattle operation led by two cowgirls. She sees them out in the pastures every morning on her way to work — "totally weathered, total bosses!" she said.

Cossart-Daly had left Hollister for a while — finishing school, experiencing a world with stable cell service. But she brought her now husband back to the ranch, where they found a home to rent.

On the way to giving birth to their first child, she had stopped on this beach, marveled at the uncrowded horizon, and envisioned sharing this world with her daughter.

She picked up a shell and got in the car. It was time to go to the hospital.

Back through the canyon, back up the steep roads with ocean cliff views, she drove past the guard and made the trek into town. These gates — the closest most members of the public have gotten to Hollister Ranch — would be open for her when she returned.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.