Ghost Ship fire mystery: What did fire officials know and when did they know it?

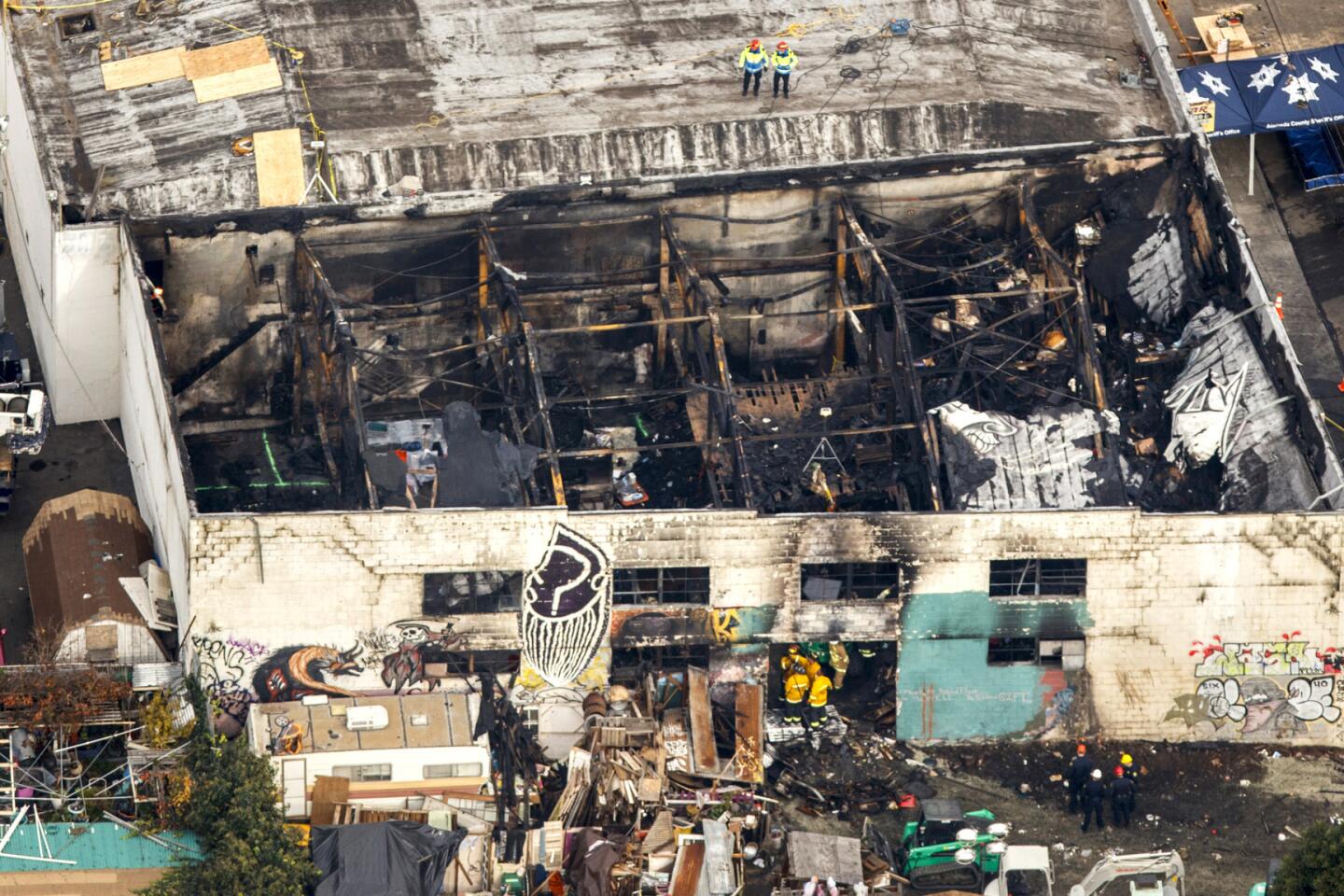

Reporting from Oakland — One of the biggest mysteries to come out of the deadly Ghost Ship fire is why authorities didn’t do more to address safety and health concerns about a warehouse that some former residents described as a “death trap.”

Fire officials said they had no record of their inspectors or firefighters going inside the building in at least 12 years, and city building code inspectors had not for more than 30 years.

But there are growing indications that some fire officials knew of at least some of the Ghost Ship’s problems.

Walker Johnson, an Oakland artist, said he saw firefighters inside the Ghost Ship on Sept. 27, 2014, during a concert.

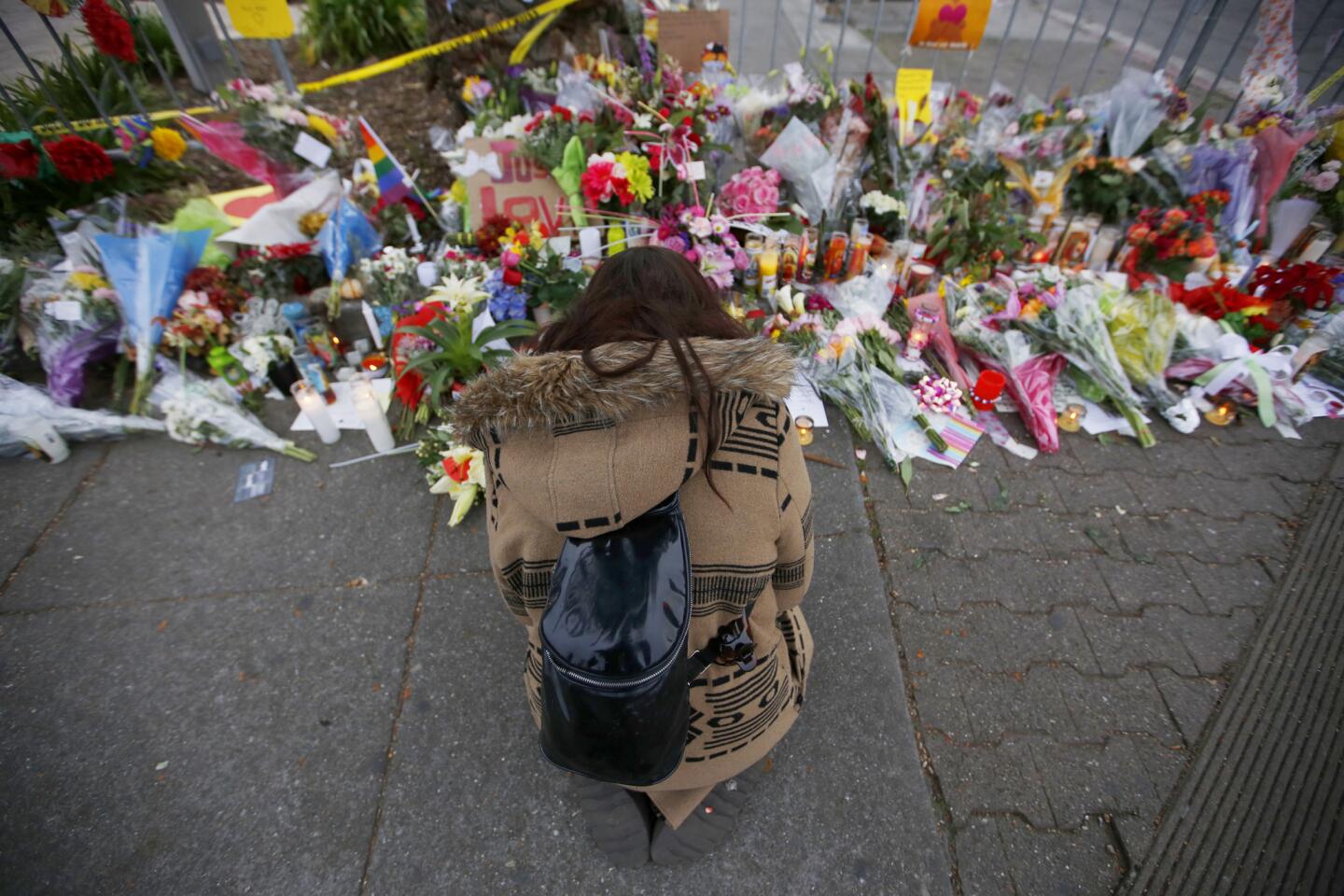

Johnson said he didn’t know why they were there but that it should have been clear the warehouse, where 36 people would die in a fire two years later, had serious safety issues.

“They couldn’t miss the danger of it all,” he said.

Johnson said he saw firefighters on the first floor but could not tell whether they went to the second floor during their visit.

The visit came as officials were hunting for an arsonist who had set several fires in the neighborhood, but it’s unclear whether it was connected to the search.

A spokeswoman for the city of Oakland said officials are looking into Johnson’s claims but could not confirm them at this time.

“We are still combing through records of service calls to the property from our various departments and will release those records as soon as we’re able,” she said.

One Fire Department source said firefighters did visit the building in the last two years but could not say whether any of the firefighters entered the structure. Station 13 sits about 500 feet from the Ghost Ship warehouse. The source spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Oakland officials are under growing scrutiny over why the warehouse was able to operate as an illegal housing complex for artists without inspections or action from the city.

Last week, officials said building code enforcement inspectors had not been inside the warehouse in at least 30 years despite the fact that the property and the lot next door had been the focus of nearly two dozen building code complaints or other city actions.

Oakland fire officials said Tuesday that they had no complaints in their records about the warehouse and that fire officials had not been dispatched there in the last 12 years.

Fire Chief Teresa Deloach Reed said a review of city records showed that the Fire Department never had any triggers to inspect the property because it did not receive any complaints, calls for service or permit applications.

She said a warehouse is an empty structure that would not ordinarily be subject to a Fire Department inspection. “There were no indications this was an active business,” she said.

But the city later acknowledged the owner of the warehouse had a business license for the location.

A spokeswoman for Oakland said owner Chor Ng obtained the license in 1995 to use the warehouse as rental property. Ng, who owns other properties in Oakland’s Chinatown district, was up to date on city tax payments, said spokeswoman Karen Boyd.

Ng owned the warehouse through a trust and managed it and other properties through her daughter, Eva Ng. She has not returned calls and messages in recent weeks. Eva Ng told The Times the day after the Dec. 2 fire that her mother had no idea the warehouse was being used for housing.

Boyd said a business license alone would not trigger a fire inspection. An inspection would occur if an owner applied for an operating or occupancy permit, she said.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that there is some kind of disconnect between city officials and some residents over the warehouse’s problems. Several former tenants as well as neighbors have said they complained to various city agencies about filthy conditions as well as unsafe structural and electrical systems. It’s unclear why these complaints did not prompt more aggressive action.

At the time of the fire, Oakland building officials had an open investigation of the warehouse. They said an inspector attempted to examine the interior of the building but could not get in.

Typically, if inspectors couldn’t get inside, they’d come back later with a warrant to gain access, according to Oakland Councilwoman Desley Brooks.

The Oakland Police Department had also entered the building, including one such visit documented in a 2015 police report.

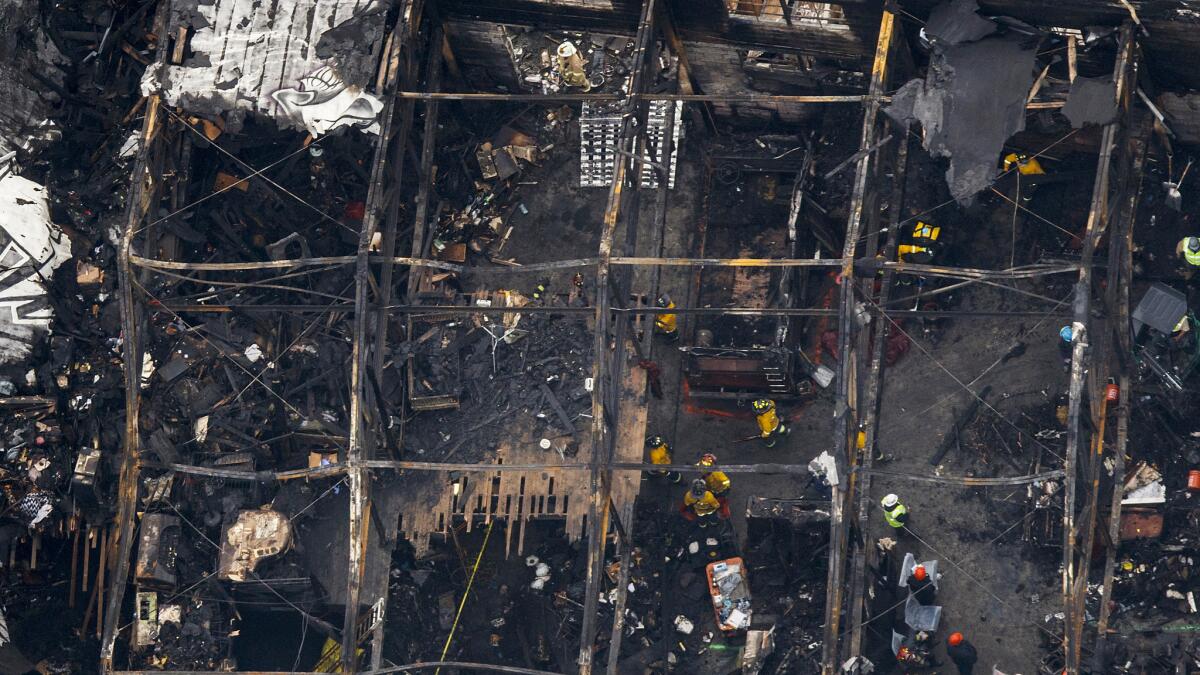

Fire Lt. Dan Robertson, president of the union that represents Oakland firefighters, said he constantly trains new recruits to keep an eye out for conditions that would make it tough to fight a fire, like clutter in the doorway, heavy locks on gates and bars on windows.

“I’ve been doing this for 27 years, and any structural firefighter that works for a big city that’s worth their paycheck profiles buildings all the time,” Robertson said. “We don’t necessarily need to step inside a building to know it’s going to be difficult to fight a fire.”

On his way to fight the Ghost Ship fire, a fellow firefighter told Robertson he knew the place and that it was like a maze, cluttered with obstacles. We’re going to have to get defensive early, he told Robertson.

Questions about the competence of Oakland’s building inspection agency arose five years ago. An Alameda County Grand Jury in 2011 released a scathing report accusing the city’s building services division of mismanagement and having haphazard policies about conducting building inspections.

The grand jury found the agency was riddled with “poor management, lack of leadership, and ambiguous policies and procedures.” It added that the agency had inconsistent standards on code violations and that the violation notices sent to property owners were late and hard to understand. In addition, inspectors treated property owners in an “unprofessional, retaliatory and intimidating” manner, the grand jury report stated.

Federal investigators said Tuesday they were still working to determine the cause of the deadly fire.

ALSO

Cities try to protect tenants while cracking down on illegal warehouse housing

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.