Gang member gets prison for firebombing black families in Boyle Heights

A gang member who helped carry out a racially motivated attack on black families living in a Los Angeles housing project was sentenced Monday to 13 years in federal prison for the 2014 crime.

Jose Saucedo, 25, received the punishment after pleading guilty last year to several felonies stemming from the nighttime attack, in which he and several other members of the Big Hazard street gang threw crudely made explosives into apartments where black families slept.

In handing down the sentence, U.S. District Judge Christina A. Snyder called the attack “a terribly violent crime,” in part because it was unprovoked, targeted innocent people, and Saucedo played a central role in planning it, according to a statement released by U.S. Attorney Nick Hanna.

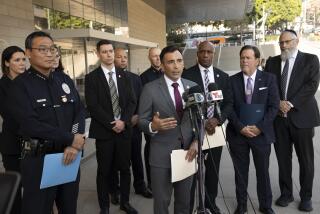

“Racially motivated crimes are among the most disturbing offenses inflicted on a community,” said Hanna. “Today’s sentence shows that criminals who are fueled by racial hatred — such as this defendant, who participated in a firebombing attack on innocent families while they slept — will face severe consequences.”

On Mother’s Day in 2014, Saucedo and seven others from the gang went ahead with a plan they had been discussing for weeks that was meant to terrorize black families living in the Ramona Gardens housing complex. In the violent, incessant turf battles between gangs, the Big Hazard gang had claimed the housing development as its territory and members wanted to rid the sprawling development of its black tenants.

With some wearing masks and wielding hammers, they smashed windows of four apartments and tossed in ignited Molotov cocktails — glass bottles filled with gasoline. Inside, families with small children were asleep, including a mother who was on a couch with her infant and narrowly missed being struck by one of the firebombs, Hanna said.

No one was injured in the attack, but the blatantly racist assault underscored longstanding racial animosity Latino gangs have stoked in Ramona Gardens and elsewhere in the city.

Several years ago, for example, federal prosecutors charged members of a Latino gang with a campaign to push blacks out of the unincorporated Florence-Firestone neighborhood that allegedly resulted in 20 homicides over three years.

And, in the Harbor Gateway district of L.A., a Latino gang was accused of targeting African Americans, including 14-year-old Cheryl Green, whose 2006 death became a rallying point against such attacks..

In Ramona Gardens, the Big Hazard gang had targeted blacks before the firebombing.

In 1992, an explosive device detonated in an apartment where a black couple and their seven children lived. Another black family across the street had been attacked the same day.

At the time, seven black families lived in the project. After the attack, they left. For the next two decades virtually no blacks lived at Ramona Gardens.

Eventually, black families started moving back to Ramona Gardens, a sign of progress in a community and a city that was working hard to put the violence of the 1990s behind it. Then came the 2014 attack. At least one resident said at the time that she would ask for an emergency transfer out of the complex. Others insisted they would stay.

In late 2016, about 4% of the nearly 1,800 people living at Ramona Gardens were black, according to city figures.

Saucedo, according to prosecutors, collected bottles to be used in the attack, supervised one of two groups of gang members during the attack and threw a firebomb into one of the apartments. Afterward, he continued to try to intimidate Ramona Gardens residents, threatening a mixed-race family that they could suffer the same fate if they did not move out.

Along with Saucedo, six others were charged and pleaded guilty to federal hate crimes and other offenses. He is the first to be sentenced and Snyder gave him credit for four years he has already served behind bars for a related offense.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.