Tentative deal to end LAUSD teachers’ strike brings celebration and disappointment

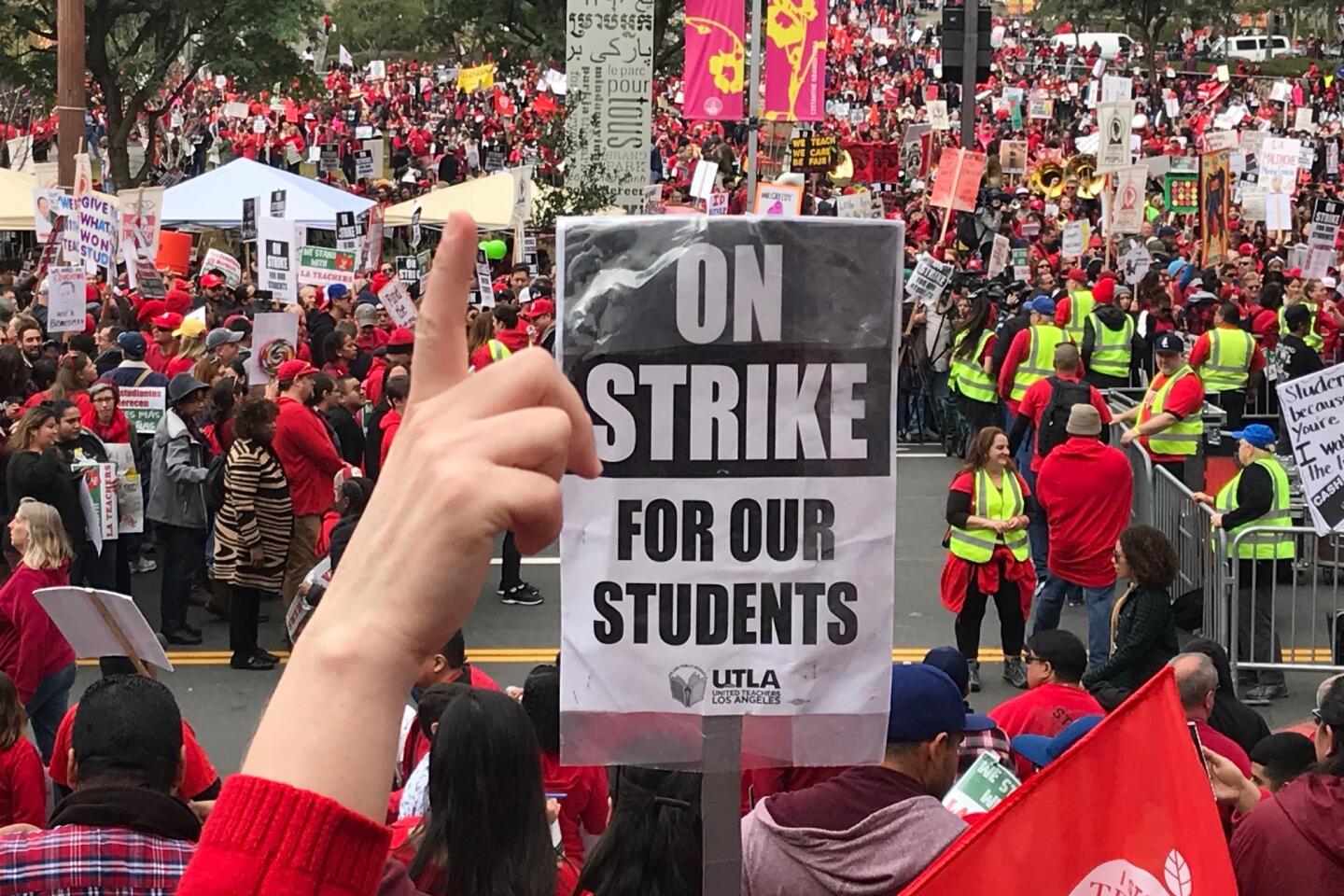

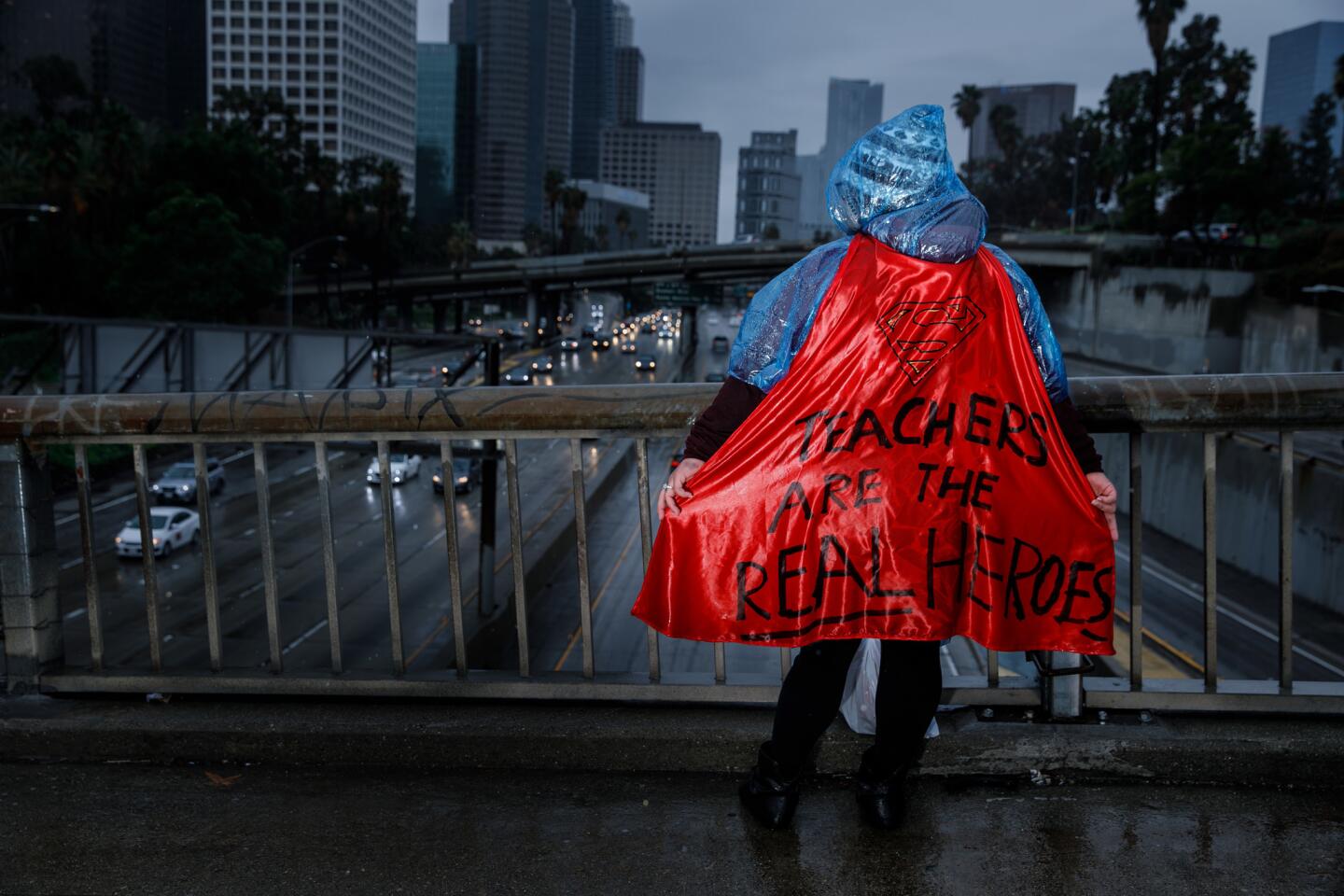

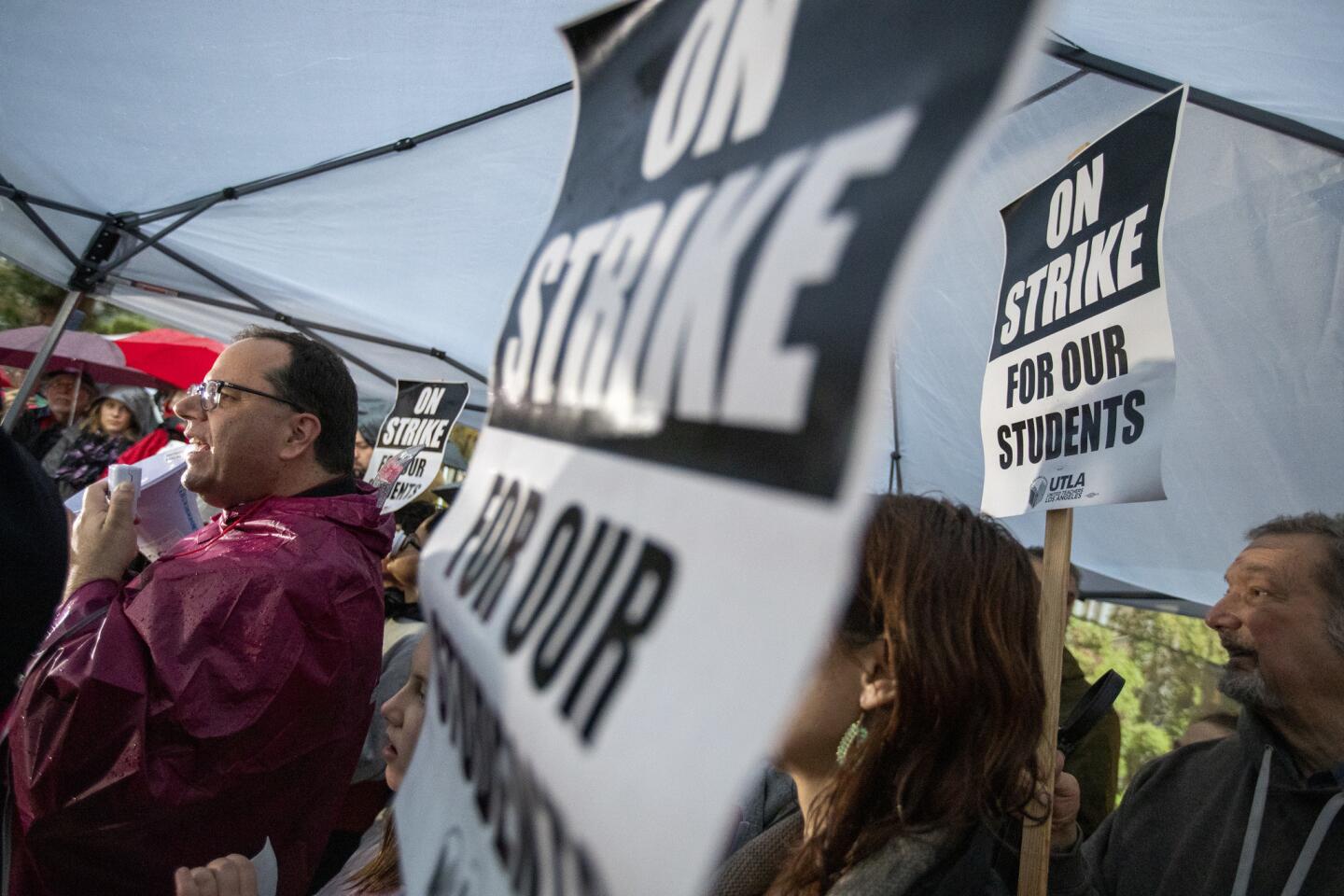

Los Angeles teachers, students and parents reacted with exhilaration — and, for some, disappointment — after union leaders reached a tentative agreement Tuesday with the L.A. Unified School District to end the strike, more than a week after it started.

The mood at a post-negotiations downtown rally was celebratory, though most of those attending didn’t yet know the details of the agreement that they were scheduled to vote on within hours.

The tentative deal includes what amounts to a 6% raise for teachers, a reduction of class sizes to levels in the previous contract and the removal of a contract provision that has allowed the district to increase class sizes during times of economic hardship. The district also agreed to further limit random searches of middle and high school students and to create 30 community schools, which would provide social services to families, rich academic programs to students and leadership roles for parents and teachers.

The strike has made teachers realize that, “we’re a lot stronger than we thought we were, so now we’re not going to let things slide,” said Nancy De La Torre, a first-grade teacher at Corona Avenue Elementary School in Bell. She’s OK knowing that the union didn’t get everything it set out for, because she feels that teachers will have more power in future negotiations, she said.

“At some point, you’ve got to compromise,” De La Torre said.

Others didn’t feel as confident about the agreement. After leaving the downtown rally, Kathleen Brown and 10 of her colleagues at Coliseum Street Elementary sat down at a Creole restaurant near their Baldwin Hills school to parse the details. Brown, a special education teacher, said she was concerned by the proposed agreement’s vague and “watered down” wording, how key wrangling points such as a proposed moratorium on charter school growth were deferred to future negotiation.

“It was not ‘when, where, with whom’ — it was just, ‘We’ll address it in the future,’” she said. “For as hard as we worked and as much as we gave up the last week and a half, I don’t think we got very much.”

For Brown, the strike was less about pay than the future of public education in Los Angeles, which she says is threatened by the folding of small charter schools into charter conglomerates with deep-pocketed and politically muscular backers.

“We wanted to make sure all kids have an equal playing field, 20, 30 years in the future,” she said. “If privatization of our schools continues, it’s going to make even more of a gap between the haves and the have-nots.”

Brown also took issue with the time frame put forth by the negotiators. As consequential as the agreement is, she’d prefer to have a whole day to think it over before voting.

“They’re giving us no time to digest it,” she said.

For Brenda Craney, whose 9-year-old great-niece goes to Coliseum Street Elementary, the agreement didn’t sound like a resounding win for teachers, especially because restrictions on class sizes were far from firm.

“That should be set in stone,” she said. “There’s no way a teacher can teach a class of 42 students.”

At 93rd Street Elementary School in South L.A., teachers lined up to fill out ballots after hearing from their union representative about the details behind the tentative agreement. Most, including fourth-grade teacher Cecilia Hamilton, voted in favor of it.

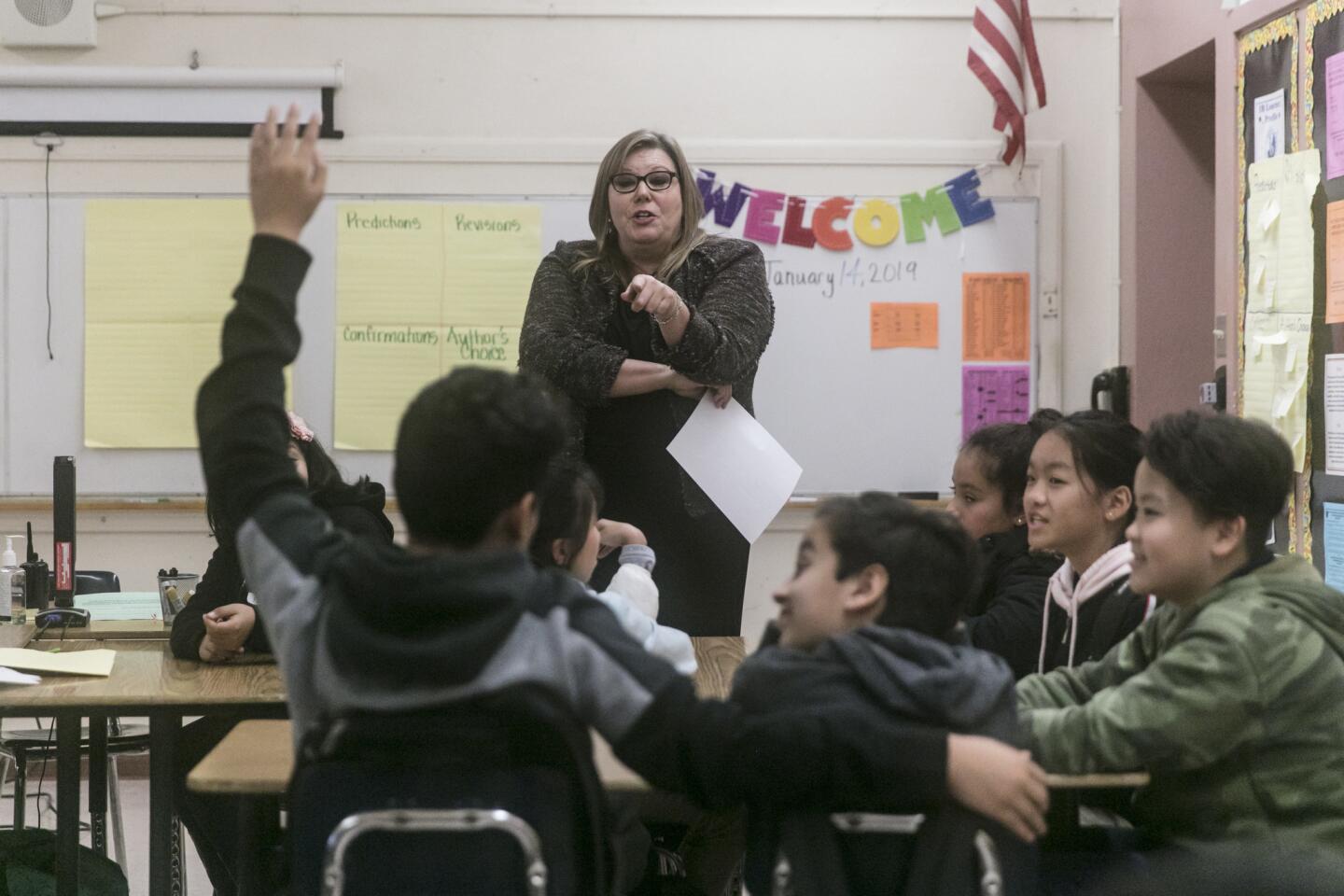

Hamilton, a second-generation teacher, said problems at 93rd Street began to worsen about six years ago as the district’s funds dwindled. Now there’s just one psychologist, no counselors and no full-time librarian. Last year, the school ran out of pens and paper. Larger classes mean she’s had less time to focus on students who are falling behind.

She looks forward to returning to school.

“It’s a start,” she said. “Now we’ve got to work with our board members, the district and the state to increase our funding.”

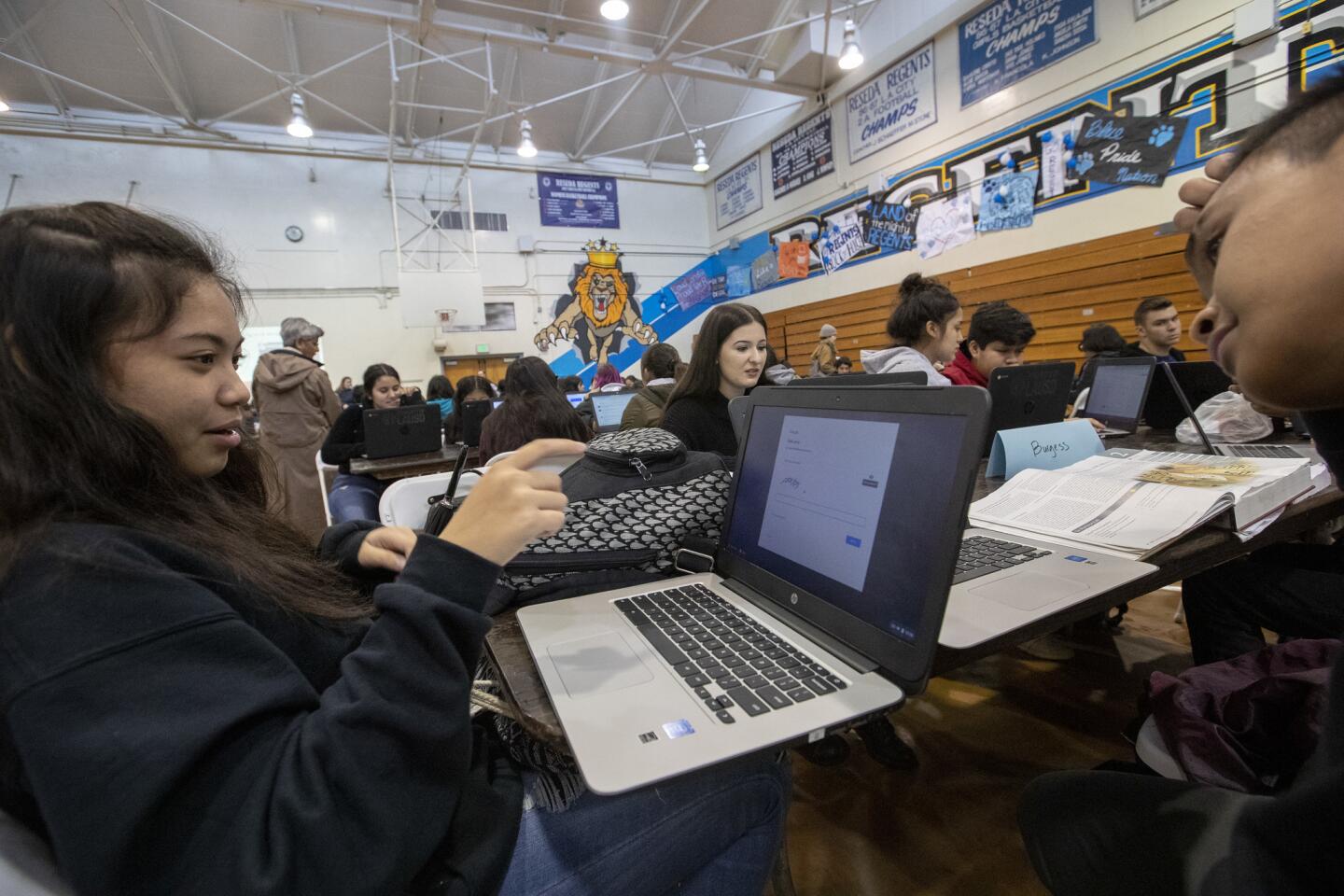

Aurora Alonso, 38, a mother of four children, said it was tough keeping her kids from watching television and playing video games. She didn’t bring her three sons to school last week. Tuesday was their first day back.

“It was a sacrifice and quite sad that it had to come to this, but it needed to be done if we want things to get better,” she said. “There’s gonna be some sense of normalcy now.”

Preschool teacher Ursula Hill said class sizes were important to her given that the district had wanted to increase preschool classes from 24 to 27 students.

“Can you imagine?” she said. “We weren’t going to get everything but there was relief we’re getting more nurses, librarians and [smaller] classroom sizes. “We were fighting for the younger generation that’s coming.”

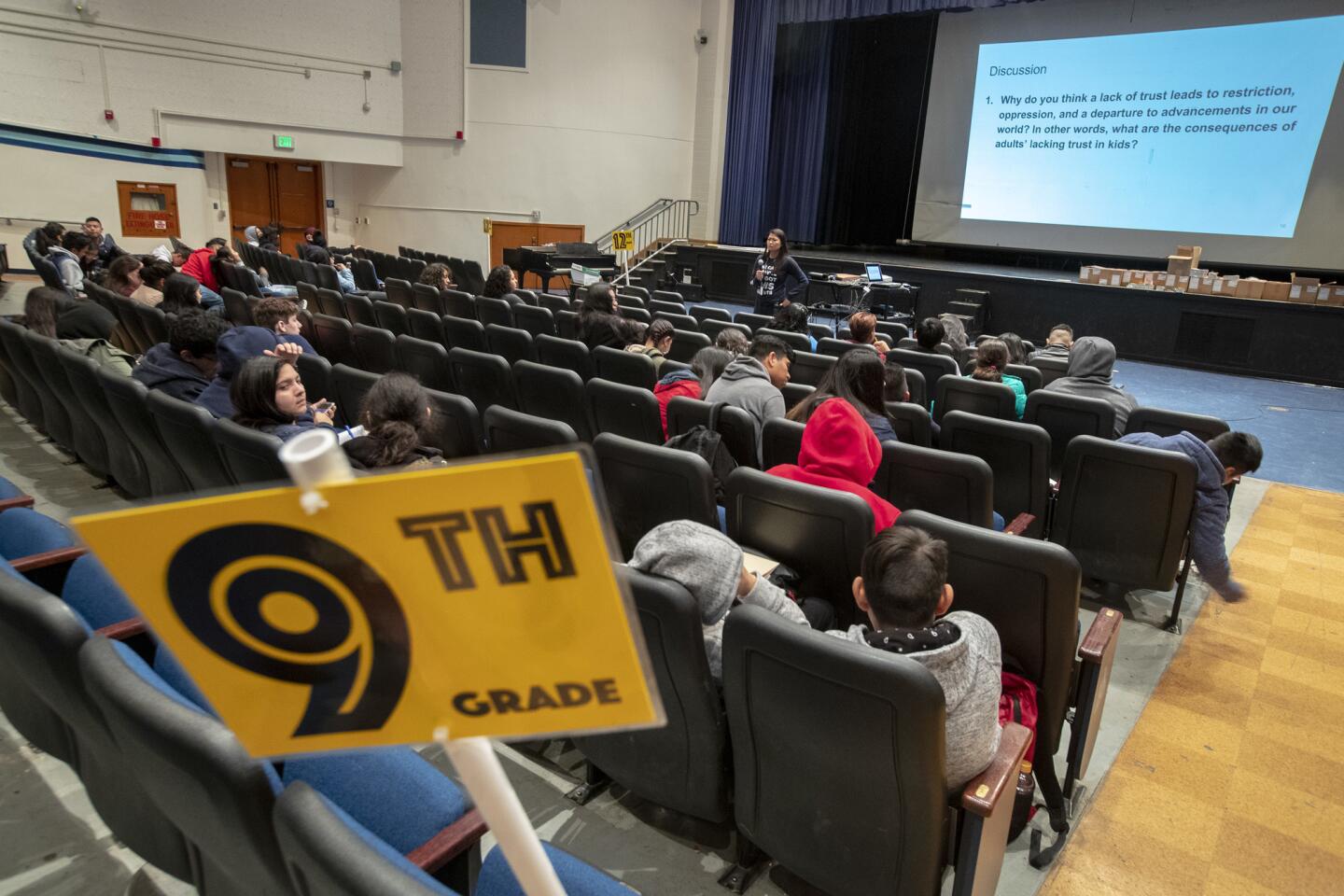

Across the city, Venice High School student Guillermo Garcia and three classmates carried a small trampoline they’d found discarded at the curb. They spent Tuesday afternoon as they’d spent last week: roaming Venice Boulevard on Bird scooters and killing time outside the classroom so as to not cross the picket line.

As fun as it was to miss classes, Guillermo, a 15-year-old sophomore, said he was happy to hear the strike was over and that teachers would be returning to classrooms with a deal that includes a pay raise and smaller class sizes.

“They’ll be able to pay attention to us more individually,” he said.

Twitter: @matthewormseth

Twitter: @latvives

Twitter: @Sonali_Kohli

Twitter: @andreamcastillo

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.