‘This is disgusting’: College cheating scandal shows ugly side of admissions game

Students and parents have long suspected that money and connections help win access to top-tier colleges.

But the federal indictments unsealed Tuesday alleging a massive nationwide scam by wealthy parents — including corporate titans and Hollywood actresses — to get their children into prestigious universities floored even the most jaded observers of higher education.

And it reinforced what many say is a drastic imbalance between the uber-rich and everyone else in the hyper-competitive college admissions game.

“This is disgusting,” said Eloy Ortiz Oakley, chancellor of the California Community Colleges and a University of California regent who has long fought for wider access to higher education. “It reinforces the notion that … if you come from wealth you have a much greater chance of acceptance than if you’re just a normal working-class American.”

Susan Paterno, a Chapman University professor who is writing a book on college admissions, said the arena has become a $100-billion business that is reshaping American culture, exacerbating income inequality, restricting opportunity and corrupting higher education’s role in the nation’s democracy.

She said she met a test-prep company executive who admitted his tutors teach students to cheat on standardized tests, and she has found firms that charge as much as $40,000 for college admissions coaching.

“This is an amazing pulling back of the curtain on what we always suspected was happening,” Paterno said of the federal indictments. “But we thought they were isolated incidents ... and didn’t realize it was so widespread.”

She added, however, that only 2% of college applicants aim for Ivy League campuses and other elite institutions. The vast majority set their sights on state and local colleges and universities, she said.

Douglas Haynes, a UC Irvine vice provost for academic equity, diversity and inclusion, said the college admissions landscape began radically shifting in the 1990s. Students who used to apply to a few local colleges could more easily try their luck at dozens of schools using centralized online admissions platforms, such as the Common Application.

Colleges began recruiting more students — both to increase diversity and to bring in revenue from application fees that helped them weather cyclical recessions, he said. At the same time, more applications lowered admission rates, which helped campuses burnish reputations as selective institutions in highly influential college rankings published by U.S. News & World Report, he and Paterno said.

As state governments reduced public support for higher education, many campuses began recruiting students paying out-of-state tuition, including many from other countries. That in turn swelled the number of applicants even more.

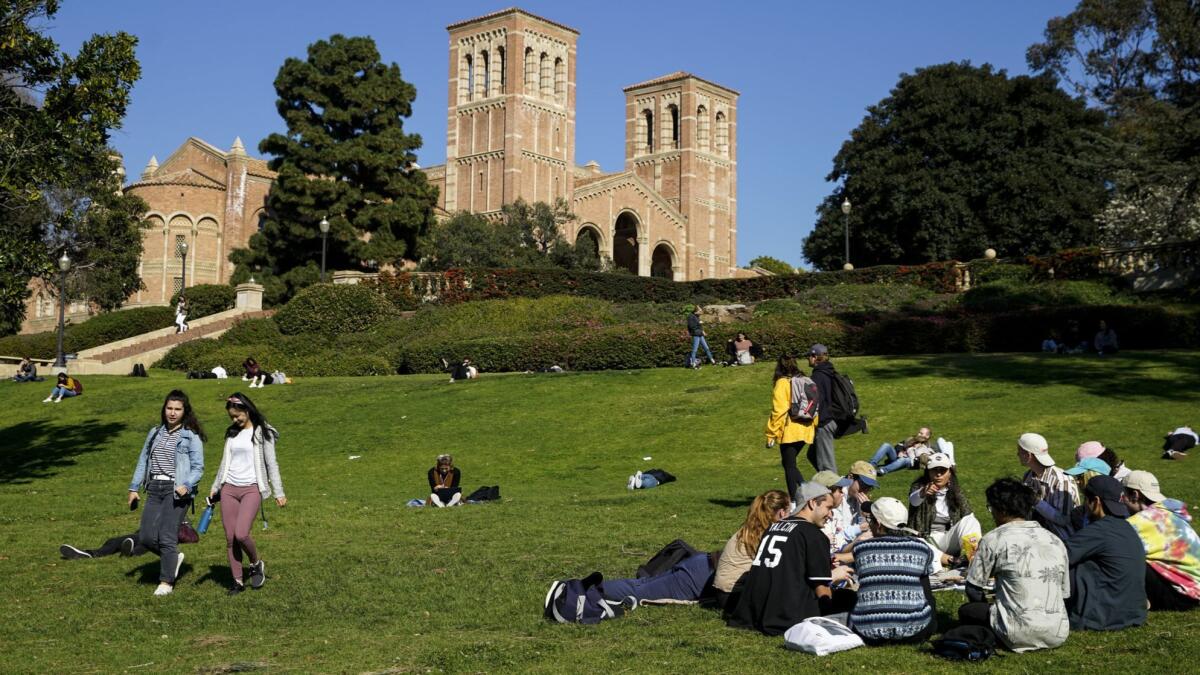

UCLA, the most popular university in the nation, now attracts more than 110,000 applications for about 6,000 freshman seats.

“All of this is driving manic competitiveness in college admissions at all levels,” Paterno said. “A lot of this hype is making families crazy.”

The University of California, the nation’s premier public research university system, has not been immune to admission and cheating scandals.

In 2007, the UCLA dentistry school was rocked by allegations that the children of wealthy donors received favorable admissions consideration in the highly competitive orthodontics residency program.

The Westwood campus subsequently prohibited influencing admissions with donations. And UC has eliminated preferential consideration for the children of alumni, a practice known as “legacy admissions” that tends to favor wealthier families.

The system also has moved toward a broader review of applicants to consider not only test scores and high school grades but also extracurricular activities, leadership and persistence over challenging circumstances, to widen access to a great swath of students.

Today, the UC system’s nine undergraduate campuses are widely regarded as powerful engines of social mobility. Four in 10 students are the first in their families to attend college, and financial aid covers tuition and fees for about two-thirds of students.

The 23-campus California State University system also admits and educates large numbers of low-income, first-generation college students. And the California Community Colleges, which educates about 2 million students across 114 campuses, has no entrance requirements, offering higher education to all.

But Oakley and others said more reforms are needed. As sensational as the alleged criminal scheme is, they say, the deeper problem is the way in which money legally gives well-heeled applicants an advantage in the college admissions game.

Mark Sklarow, chief executive of the Independent Educational Consultants Assn., said donations can still give wealthy applicants a leg up. The process, which he said he’s not a fan of, doesn’t operate as a quid pro quo but as more of a wink and a nod. For example, Sklarow said someone in the donation office might promise to “walk it over to the admissions dean’s office” and ensure that they know about the significant gift.

Michael Dannenberg, a director with Education Reform Now, said that “binding early decision” programs, which give an edge to those who commit early to colleges but stop applicants from shopping around for better financial aid options, also favor the wealthy.

Varsha Sarveshwar, a UC Berkeley junior majoring in political science, said she knows people who have paid thousands of dollars for test prep and hired private college counselors as early as their middle school years to guide their class selection and extracurricular activities.

In other cases, wealthy parents have sent their children abroad for volunteer work or helped them start businesses to burnish their college resumes.

“It’s pretty clear there’s a lot of deep-rooted inequity in the system,” Sarveshwar said.

She and Oakley say colleges should make SAT and ACT tests optional for college admissions — a proposal that the UC and CSU systems are considering.

Paterno advocates government oversight of the unregulated college consulting industry and more generous state and federal funding to help middle-class, working-class and low-income students earn affordable college degrees.

Such funding should, for instance, provide more college counselors for public high schools, she said. Other reform ideas include limiting federal work-study and merit aid programs to needier families and redirecting to community colleges money for subsidies and tax credits to for-profit colleges.

Oakley added that other states should emulate California’s robust financial aid program, among the most generous in the nation. He supports eliminating legacy admissions and college rating systems that favor the wealthy.

“The real scandal is what is legal in college admissions,” Dannenberg said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.