Can L.A.’s aging Grand Dame, Memorial Coliseum, take center stage one more time?

The seats creak and the rows are so narrow that Rams fans might find their knees in position to do duty for the cup-holders that they won’t find in their armrests. The low entrance tunnels feel like they were built for hobbits.

The Rams return Sunday to Los Angeles to the same stadium they left 37 years ago — one built for the thinner, shorter, less-pampered Angelenos of the 1920s.

For the record:

10:30 p.m. Oct. 29, 2024An earlier version of this article misspelled Jesse Owens’ first name as Jessie and Rosey Grier’s first name as Rosy.

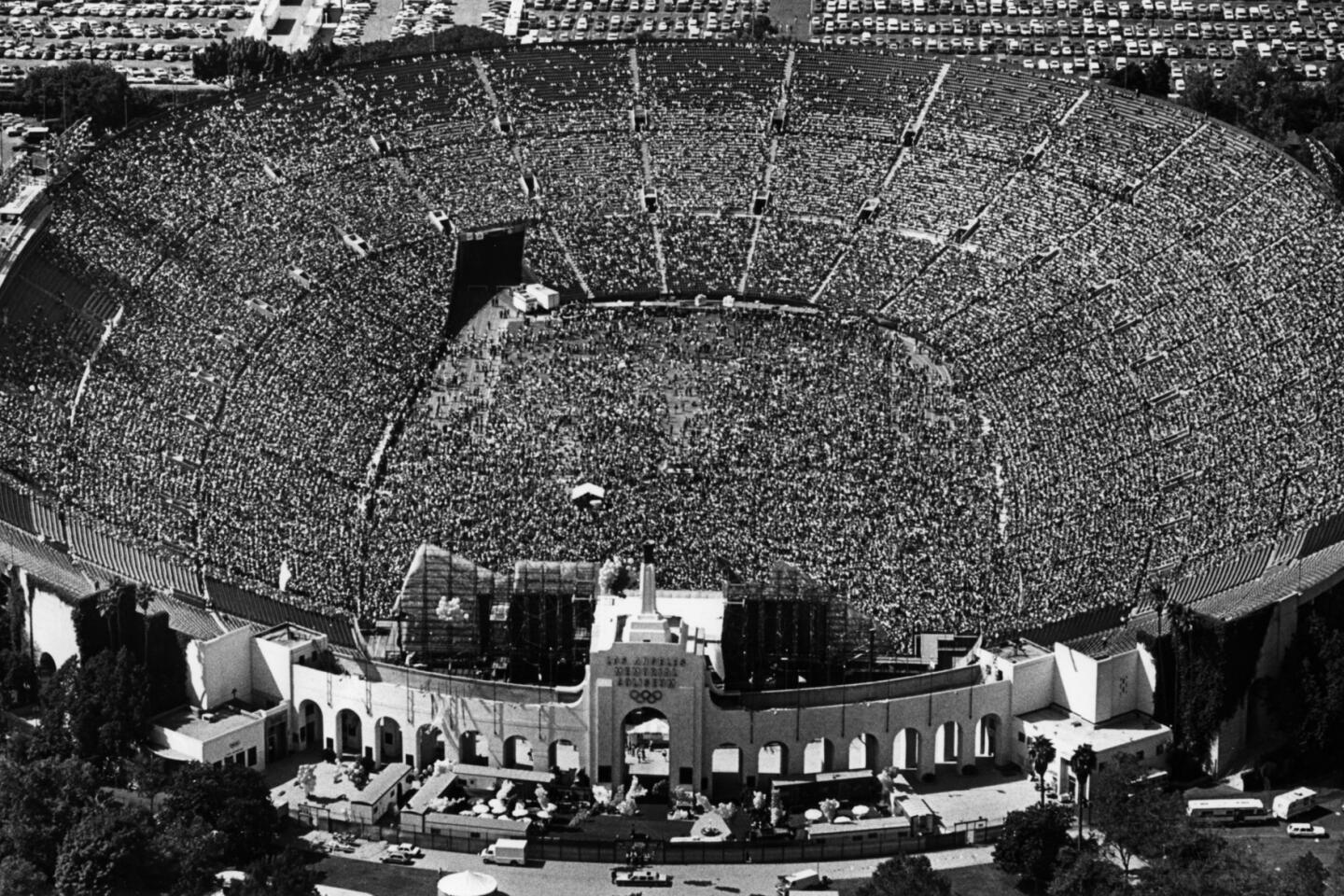

But the arena’s grandeur has never shrunk with the times. The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, the centerpiece of Los Angeles’ current bid for the 2024 Summer Olympics, rose from the dirt at the peak of a remote city’s boundless ambition — a city that had just engineered the largest aqueduct on earth, had become the world capital of the motion picture industry and was vying for official stature as a global city by hosting the Olympics.

The Coliseum had a huge influence on the evolution of Los Angeles.

— Frank Guridy, Columbia history professor

Newcomers are still struck by the soaring marbled arches of the peristyle that evoke the ancient Colosseum of Rome. And its age draws out an even deeper awe — for the sports legends and historical figures who have passed through.

Jesse Owens broke the stadium’s track records here, running for Ohio State. FDR spoke here during the height of the Great Depression. Jackie Robinson became a collegiate football star, tearing up the field with long breakaway runs as a UCLA running back, long before he went on to desegregate major league baseball.

Gen. George S. Patton and returning soldiers converged at the stadium to celebrate Germany’s defeat in front of 105,000 people — with a fly-by of B-29 Superfortresses to signal impending doom for imperial Japan.

The Dodgers of Duke Snyder, Maury Wills, Don Drysdale, Sandy Koufax won the pennant here in 1959, in just their second year out of Brooklyn, with Vin Scully doing the play-by-play.

JFK stood on the Coliseum steps to give his nomination address in 1960 — his famed “New Frontier” speech.

And could anything represent 1973 America better than Evel Knievel launching his motorcycle over 50 stacked cars?

Two Olympiads, Super Bowl I, a Billy Graham crusade, O.J. Simpson, Marcus Allen, Reggie Bush, Martin Luther King Jr., the Rams’ Fearsome Foursome, Carl Lewis, Mary Decker, Nelson Mandela, Bruce Springsteen, the Rolling Stones, Al Davis, Raider Nation.

All of that is infused in the arena right down to the rusted seats.

“It’s our big place serving the needs of the great metropolis for all kinds of things,” said William Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West. “Recreational, political, social, spectacle, musical, religious.”

It’s our big place serving the needs of the great metropolis for all kinds of things, recreational, political, social, spectacle, musical, religious.

— William Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West.

For most of the city’s history since its cow-town days, the Coliseum was the place where Los Angeles came to gather.

The stadium was first conceived as a memorial to veterans of the Great War. For a location, supporters chose the new Exposition Park, which had just replaced the old Agricultural Park, a den of gambling, drinking and prostitution, and an illicit lure for the students from then Methodist USC.

The Coliseum was championed by real estate developer William May Garland, who saw it as the key element to draw the Olympics to Los Angeles. His commission hired the pre-eminent father-son architects, John and Donald Parkinson, who had designed the Romanesque Revival buildings at USC, and would later design Los Angeles City Hall and Union Station. They used Egyptian, Spanish and Mediterranean Revival styles for the monumental Art Deco stadium.

Three-hundred-thousand cubic yards of dirt were removed to create the playing field — 30-feet below grade — and bulldozed into a colossal oval berm, upon which the poured concrete super-structure of the stadium would be built. They designed it to accommodate 75,000 people, at a cost of $954,000.

In its first year, the Trojans football team played there. The next year, 30,000 people showed up to watch as Jack Dempsey “slammed the tar out of three different opponents” in May 1924.

When Los Angeles finally secured the Olympics for 1932, the Parkinsons added another tier to bring capacity to 101,000, as well as the famous Olympic cauldron above the peristyle.

In the midst of the Depression, Los Angeles officials worried the games would cost the city a fortune. Instead, the games generated $1 million in profits and left the city with much of the infrastructure needed for an even more successful Olympiad in 1984.

When Patton took the stage at the Coliseum he was coming home to a city transformed from the dusty backwater he grew up in. As a teenager he had left Southern California for military school in Virginia, but he had deep roots here. His grandfather, Benjamin Wilson, was the second mayor of Los Angeles under U.S. rule (Mt. Wilson is named after him) and his father was district attorney.

Now, after years of forced blackouts during the war, searchlights scoured the skies over the Coliseum. Movie star Edward G. Robinson narrated the story of “Old Blood and Guts’” fighting career and Humphrey Bogart told the story of Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle, a hero pilot in the Pacific theater who received the Medal of Honor.

“The Coliseum was transformed with the magic of Hollywood into an arena where Patton’s 3rd Army tanks again spearheaded the thrust toward the Rhine, toward Berlin, toward victory in Europe,” The Times wrote.

Two years later, the Rams arrived from Cleveland, the first NFL team west of the Mississippi. And Jackie Robinson’s old teammate at UCLA, Kenny Washington, joined the team to become be the first African American to integrate that league.

When the Dodgers arrived, officials had to somehow fit the wide cone of a baseball field into the ovoid. The left field line would run just 251-feet deep. Aficionados cried foul, fearing Babe Ruth’s sacred home-run record would be broken by Dodgers hitting easy pop flies to left field. To address it, and protect fans, the stadium put a 42-foot screen behind the wall. A hit would have to clear it to be a home run. Still, outfielder Wally Moon became famous for his “moon shots” which just made it over the screen.

The pinnacle of the Coliseum’s 93 years came the next year, 1959, when the stadium hosted USC, UCLA, the Dodgers, the Rams, a baseball All Star Game and the World Series.

Tom LaBonge, the former L.A. councilman, remembers the exhilaration of walking through the tunnels to see the field below and the great peristyle. “It felt like the biggest place in the world.”

He calls it the “cathedral on 39th and Figueroa.”

As a teenager in the 1960s, he loved to watch Deacon Jones, one of the Rams’ “Fearsome Foursome” — the starting defensive line, with Rosey Grier, Lamar Lundy and Merlin Olsen. When Jones died in 2013, LaBonge helped his family hold a memorial at the Coliseum because of Jones love for the place.

“The Coliseum had a huge influence on the evolution of Los Angeles,” said Frank Guridy, a Columbia University history professor who is writing a book about the stadium. “It helped put L.A. on the map, nationally and internationally.”

But it took a major hit when the Rams departed for Anaheim in 1979. UCLA jumped to the Rose Bowl three years later, and the Raiders moved back to Oakland in 1994. When Staples Center opened in 1999, many of the big rock and pop acts went there, and revenue at the stadium plummeted.

With USC its only mainstay, Coliseum officials rented the taxpayer-owned stadium for soccer games, all manner of festivals, and drug-fueled raves, including one in which a 15-year-old girl fatally overdosed on Ecstasy.

Now, on the sacred turf where Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers came from behind to defeat the Kansas City Chiefs in the nation’s first Super Bowl and where Pope John Paul presided over mass for 103,854 souls — filmmakers shot a 40-minute group sex scene for “The Gangbang Girl #32.”

That sordid mess came to light in 2011 when a Times investigation dug up a massive bribery and embezzlement scheme orchestrated by the stadium’s event manager, Todd DeStefano, who was sentenced to six months in jail on Thursday and ordered to pay the commission $500,000. Prosecutors suggested that more than $2 million embezzled from the Coliseum Commission helped lead it toward “financial ruin.” The commission gave control of the facility to USC.

The Rams will undoubtedly give the Coliseum a new dose of energy, even if their stay is only for three years—and even if they aren’t, like Patton, arriving triumphantly. They lost their opening game to San Francisco 28-0, and are facing Pete Carroll’s Seattle Seahawks at a venue he knows well from his nine years coaching USC. (Coliseum staff had to cover an image of Carroll in the locker room that the Rams will now share with the Trojans.)

USC plans to use the infusion of cash for major renovations it had been asking from the commission for years. And with the new Expo line, spectators, like those who came to see Jack Dempsey in Pacific Electric Red Cars, don’t have to mess with Coliseum’s notoriously nightmarish parking.

LaBonge, for one, can’t wait to see his old team back home.

“On Sunday when 90,000 people welcome the Rams back, and the team comes running through that tunnel, the Coliseum will stand tall again.”

ALSO

Rams odd jobs: It’s a dirty job, but somebody’s got to do it

Excavation for new Rams stadium could start in two to three months

Rams prepare to dig in Inglewood, but NFL stadium drama is far from over

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.