California’s most destructive wildfire should not have come as a surprise

Reporting from PARADISE, Calif. — The Camp fire raging in Butte County and the Tubbs fire that torched Northern California’s wine country are a year and 100 miles apart. But they have much in common.

Flames and embers, pushed by strong dry winds out of the north and northeast, setting a town ablaze. Thousands of buildings destroyed. Fleeing residents burned to death.

Both burned their way into the record books by searing areas that have burned before — and will undoubtedly burn again.

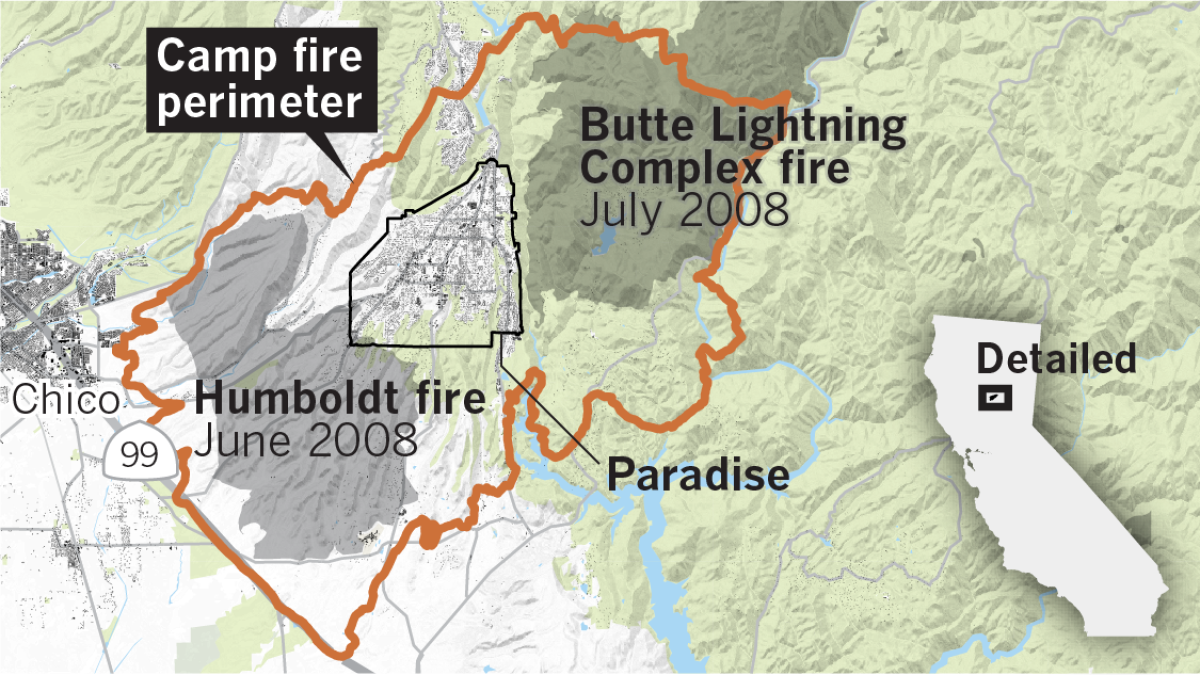

By Friday night, the Camp had destroyed more than 6,700 buildings as it leaped across land scorched a mere decade ago in a siege of Northern California lightning fires.

The Tubbs erased entire neighborhoods in Santa Rosa, sprinting across the same oak-studded grasslands blackened a half-century earlier by the wind-driven Hanley, when there were far fewer homes to burn in the region.

California’s wildfire narrative is one of repetition.

“We have these Santa Ana-like events happening in places that are appearing to catch people by surprise,” said Max Moritz, a cooperative extension wildfire specialist at UC Santa Barbara’s Bren School. “But they shouldn’t be catching people by surprise.”

“These are areas that have burned before,” he said. “And if we were to go back and do the wind mapping, we would find that at some intervals, these areas are prone to these north and northeasterly Santa Ana-like events.”

They go by different names — Santa Anas, sundowners, diablos — but autumn winds that gain heat and speed as they blow from the interior down the state’s mountain ranges are inevitably the prime ingredient of California’s most destructive wildfires.

The Camp fire started at 6:30 a.m. Thursday in a granite canyon with steep slopes. By 10 a.m., it had ballooned to 5,000 acres, pushed by 50-mph gusts from the northeast.

“This got up and going really, really rapidly,” said Dave Sapsis, a wildland fire scientist with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. “It had almost a direct-arrow line” to Paradise, a town of 27,000 sitting atop a ridge in the Sierra Nevada foothills.

“We were told about a red-flag warning, a big heavy wind,” said Butte County Sheriff Kory Honea. “It’s not uncommon for a wind to blow through that area, but the wind event we were experiencing was above average and contributed to how rapidly this fire moved through. You get to a point where you can’t get ahead of it. You can’t get ahead of the fire.”

Within the fire’s first hour, the sheriff was helping direct traffic off the ridge.

“It’s the morning time and it’s like pitch black, the middle of the night. Ash and embers are raining down on you, and you are trying to get people going,” he said.

“There’s this quote, being in ‘the fog of war.’ That is exactly what it feels like,” he added. “You’re trying to figure out where the fire is coming from and what’s going on. It becomes very, very difficult to keep track of all of the moving parts.”

First, residential areas went up in smoke. Then flames erupted in the Paradise business district, skipping around the town’s main drag. “You’ll see two or three businesses burned out and one survives,” Honea said. “It’s … an absolute tragedy for my community.”

The property loss wrought by the Camp fire has eclipsed the modern record set just a year ago by the Tubbs, which leveled 5,636 buildings in the wine country and left 22 dead. At least 23 people have died in the Camp, some of them killed when their vehicles were overtaken by flames.

In July, the fast-moving Mendocino Complex fire in Northern California charred 459,123 acres, becoming the largest wildfire in modern state history and bumping last December’s, wind-driven Thomas fire in Southern California to second place.

Moritz argues that the state has learned little from this stunning trail of death and destruction.

“We are failing ourselves,” he said.

“We have all kinds of tools to help us do this smarter, to build in a more sustainable way and to co-exist with fire,” he said. “But everybody throws up their hands and says, ‘Oh, all land-use planning is local. You can’t tell people that they can’t build there.’ And the conversation stops right there.”

The new houses rising from the ashes in Santa Rosa will have fire-resistant trappings such as sprinkler systems and double-paned windows, but the city is not curbing rebuilding in fire zones.

“We had these epic, terrible events last year and our governor came out swinging, talking about climate change. [But] he ended up with decrees and bills that focused on thinning the forest,” Moritz added.

There was “a lot of potential for progress in terms of building codes and design and building more fire-resistant communities. The legislation that could have gone forward didn’t. We dropped the ball,” he lamented.

Forest thinning would not have stopped the Camp or the Tubbs. Fueled by dry grass growing amid scattered pine and oak trees, the Camp tore across land thinned by flames just 10 years ago. The Tubbs burned grassy oak woodlands, not timber land.

Wildfires have blackened more than 1.5 million acres in California this year, most of it in Northern California. That outstrips 2008, which, at nearly 1.4 million acres, had held the record for the most burned in any single year in recent decades.

The Southern California Woolsey fire and the Camp will push that number even higher.

And the Southland’s Santa Ana wind season has a couple of months to go.

Twitter: @boxall

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.