Workers claim injuries all over their bodies for big payouts — but continue their active lives

Former LAPD Officer Jonathan Hall was filmed teaching scuba, biking and lifting heavy equipment while on injury leave. The city paid him $97,000, tax-free, for his time off.

After nearly two decades on the force, former LAPD Officer Jonathan Hall ended his career the way many veteran officers do these days, claiming job-related injuries across most of his body.

With the help of a boutique Van Nuys law firm that specializes in workers’ compensation cases for cops and firefighters, Hall filed claims saying he’d injured his knees, hips, heart (high blood pressure), back, right shoulder — even his right middle finger.

The ailments had existed for months, in some cases years, and had not previously prevented him from working, Hall said in a recent interview. But he was burned out, the target of an internal affairs investigation and desperate to avoid going back to the station.

“I just couldn’t put the uniform back on,” Hall said.

Hall’s timing raised suspicion, and he was soon videotaped leading scuba dives and lifting heavy equipment despite the alleged injuries.

But he’s far from alone in asserting that so many parts of his body had been injured on the job.

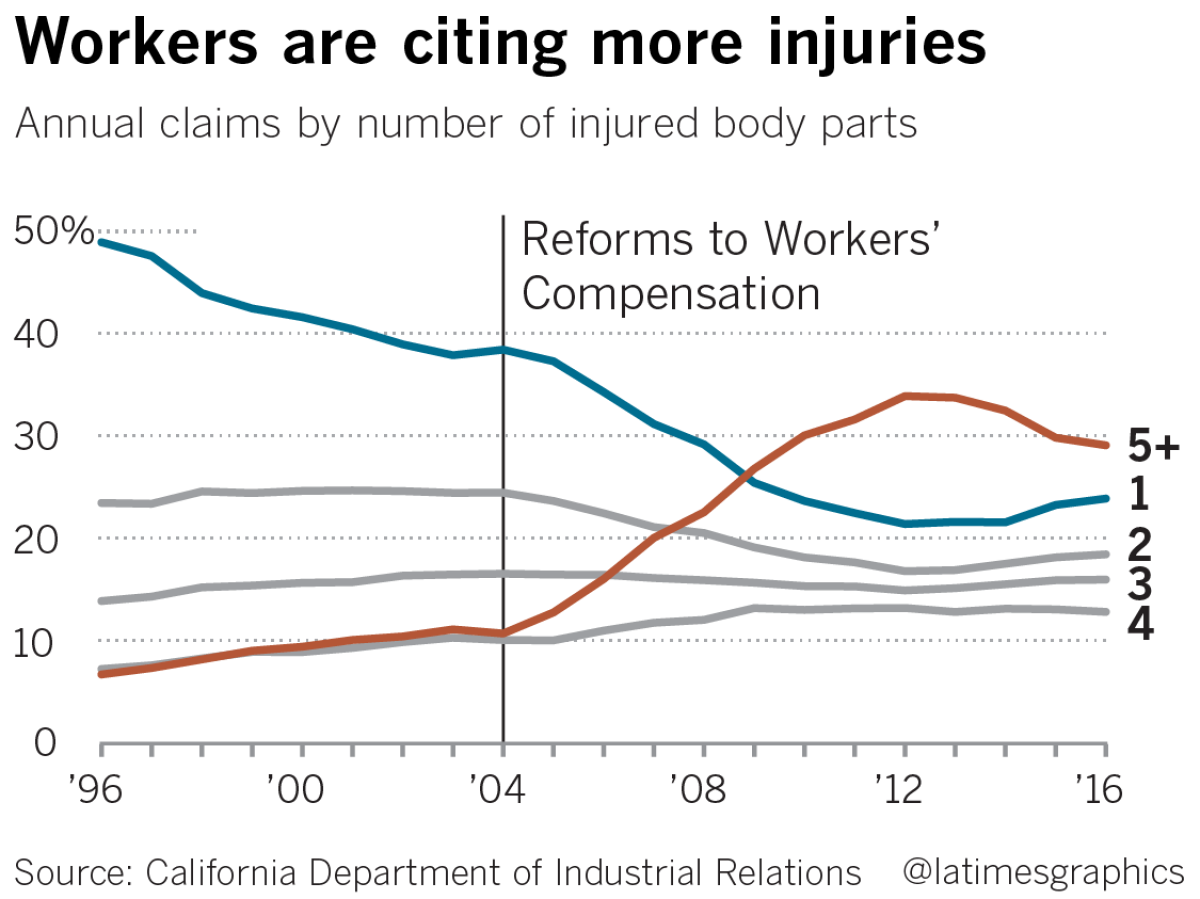

In fact, claims involving at least five injured body parts have become by far the most common in California, according to a Times data analysis of millions of workers’ compensation cases spanning nearly three decades.

In the past, injuries to a single body part — a knee, a shoulder, the lower back — were the most prevalent, the data show.

That changed abruptly in the mid-2000s when then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger pushed through legislation that drastically lowered the amount that can be paid out in benefits for each injured body part.

Lawyers for injured workers responded by simply increasing the number of body parts per claim, said Paul Young, an attorney who was a partner at two high-profile Los Angeles-area law firms that represent cops and firefighters. He was a co-founder of Straussner Sherman, the firm that represented Hall.

“That just changed the whole system,” said Young, who has since left Straussner Sherman and now defends employers in workers’ compensation cases.

Another attorney who worked at an L.A. law firm catering to injured cops and firefighters in the mid-2000s, who asked not to be named in order to avoid professional reprisal, put it this way: “An arm used to be worth $30,000, and now it’s $10,000. So let’s throw in heart problems and a bad knee to get it back to up $30,000.”

The strategy is common among veteran cops and firefighters who get up to a year off at their full salary, tax free, for each job-related injury their doctor diagnoses. Their employers also pay the associated medical bills and often a hefty cash settlement based on the extent and severity of the injuries, a cut of which goes to the injured officer’s attorney.

Multiple lawyers and patients involved with the workers’ compensation system described a similar process: An officer nearing the end of his career goes to an attorney’s office complaining about a sore shoulder and is asked how his knees feel, if his back aches or if he is under a lot of stress. He is then referred to a doctor with whom the attorney has a long-standing relationship.

After a few decades on the job, it’s not hard for a client to fill out what industry insiders call a “skin and contents” case, Young said. “I’m 52, and if somebody asked me what hurts I could start from the top and work my way to the bottom.”

In a recent interview, Schwarzenegger said he introduced the 2004 overhaul in response to a historic increase in medical costs and workers’ compensation insurance premiums in California, which had tripled since 1999.

But it was also personal. Schwarzenegger said he had been shocked at the level of abuse he encountered at the gym in Venice where he trained to be a bodybuilder. He’d see guys working out twice a day and ask what job allowed them to devote so much time to training. “They would say ‘workers’ comp’ without beating around the bush or offering any justification,” Schwarzenegger said. “It infuriated me.”

So in his first year as governor, Schwarzenegger replaced California’s unusually generous schedule of payments for injured body parts with nationally accepted standards set by the American Medical Assn.

Under those guidelines, fewer injured workers qualified for cash settlements, and those who did got about 60% less per body part, said Frank Neuhauser, a UC Berkeley researcher who studies the California workers’ compensation system.

“That was a really dramatic shift,” Neuhauser said.

The response from injured workers, their attorneys and doctors is clear in data from the state Workers’ Compensation Appeals Board, which hears cases involving disputed claims. In 2004, the board reviewed 16,000 claims with five or more body parts. By 2016, the number had more than doubled, to 38,000.

Thousands of such claims have been filed by participants in Los Angeles’ controversial Deferred Retirement Option Plan — or DROP, as it’s known — which allows veteran cops and firefighters to collect their salaries and pensions simultaneously for the last five years of their careers.

A Times investigation in February found that nearly half of the people who have joined the program since its inception in 2002 subsequently went out on injury leave — at nearly twice their normal pay — typically for bad backs, sore knees and other injuries that afflict aging bodies regardless of profession.

Their average absence was 10 months, but hundreds stayed out for more than a year, The Times found.

The program has paid out more than $1.6 billion in early pension checks to city cops and firefighters; the average participant who exited in 2016 walked away with an extra $434,000, The Times found.

Former Los Angeles Fire Capt. John Kitchens was paid more than $1.5 million while in DROP — $645,000 of that in extra pension payments — despite missing more than a year and a half on injury and sick leave, city payroll records show.

About halfway through the program, Kitchens claimed injuries to 13 body parts — including his neck, back, shoulder, knees and ankles — through “cumulative trauma” over the course of his career, city records show. That meant he did not have to provide specific dates on which the injuries occurred or describe particular incidents that caused them.

Job-induced cumulative trauma was also responsible for his high blood pressure, acid reflux, skin cancer, kidney cancer and sleep apnea, Kitchens claimed.

In addition to Kitchens’ paid time off and the overtime that the Fire Department had to pay another captain to fill his empty shifts, Kitchens’ claim cost the city $225,000 in direct payments to him, his attorney and medical providers, city records show.

Despite his health issues, Kitchens was able to travel to the Galapagos Islands in January 2013 to dive with hammerhead sharks, according to his Facebook page.

In the comments beneath a photo of him in scuba gear on a boat at Gordon Rocks — a bucket-list destination for many divers — his only complaint was that the photos he took of the massive sharks underwater turned out blurry.

“I understand, from an outside viewpoint, what this looks like,” Kitchens said in a recent interview. “But, honestly, I am in constant pain.”

After a bout with kidney cancer in 2010, Kitchens said a union representative told him he needed an attorney to help him file a workers’ compensation claim. Under state law, cancer is presumed to be job-related for police and firefighters.

Before filing the successful claim in April 2012, Kitchens said, his attorney told him to list all of his physical ailments, even the minor ones. “He told me this is the system,” Kitchens said.

“I don’t think it was in the sense of padding the claim, but in the sense of being thorough,” Kitchens said. “Although you’d have to ask the attorneys and the doctors what their motives were.”

Kitchens’ attorney, Roger Cognata, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Glenn Martinez, a former building inspector for the Los Angeles Fire Department, had already filed at least nine workers’ compensation claims over his 30-year career when he joined DROP in 2014. Two years later, his supervisors accused him of falsifying documents and collecting overtime pay for after-hours safety inspections they said he never actually performed.

The sites of the alleged phony inspections included multiple buildings at USC, two buildings at Occidental College and a tiny Lincoln Heights elementary school that had, it turned out, been shut down two years earlier.

In October 2016, as the department investigated the allegations, Martinez and his attorney filed a tenth workers’ compensation claim — for stress.

After that, Martinez rarely showed up for his $230,000-a-year job, taking most of the time off sick, city payroll data show.

Then, in August 2017, while the investigation remained open, Martinez and his attorney claimed he had suffered cumulative trauma to his heart, neck, elbows, wrists, lower back, shoulders, knees, ankles, feet, lungs and skin, city records show.

The cumulative trauma was also responsible for his sleep disturbance, acid reflux and sexual dysfunction, according to the claim.

Martinez retired from the Fire Department in March after he had been scheduled for an internal disciplinary hearing to face the phony inspection allegations.

When two Times reporters recently knocked on the door of Martinez’s Whittier home — which had a BMW and a Mercedes-Benz parked in the circular driveway, each with an LAFD decal in the rear window — a fit, tanned man in his late 50s who bore a striking resemblance to photographs of the former fire inspector answered, but he claimed he was not Glenn Martinez.

Asked about the allegedly falsified safety inspections, he said, “That’s already been out there”, referring to a 2016 KCBS report in which Martinez was confronted on camera and asked about the inspections. He didn’t answer then, either.

Asked about the workers’ compensation claim with 14 injured body parts, he said, “That’s inaccurate,” then shut the door. Martinez did not respond to several follow-up voice messages requesting more information.

Martinez’s attorney, Aaron Straussner of Straussner Sherman, declined to comment.

Hall, the former officer who was also represented by Straussner Sherman, said in a recent interview that he filed his injury claims as a “last-ditch effort” to get out of going into work at the Los Angeles Police Department in 2012.

Two years earlier, he and his wife had purchased a small scuba shop at the foot of the Belmont Pier in Long Beach, a short distance from their house.

After running afoul of a supervisor at the LAPD — who launched an internal affairs investigation accusing Hall of trying to dissuade other vendors so his new business could win a contract to sell dive equipment to the department — Hall said he couldn’t face returning to work.

So he requested an unpaid leave of absence to upgrade his scuba instructor’s certification. When the department denied that request, Hall filed the workers’ compensation claims.

Hall collected more than $97,000 in tax-free salary while he was on leave to recover from his long list of injuries, payroll records show.

During that paid time off, undercover LAPD officers filmed him teaching scuba lessons at his shop, Deep Blue Scuba & Swim Center.

In a subsequent deposition, Hall admitted to diving while on leave but claimed he had not taken paying students into the ocean or dived off a boat. The undercover video clearly showed him doing both of those things. Hall was fired and convicted of a misdemeanor for lying during the deposition.

As for his injuries, Hall said that the high blood pressure was serious and that his shoulder “hurt terribly during those dives,” although his body language in the videos suggests no obvious distress.

The other injuries, though confirmed by his doctors, were less debilitating, Hall said.

Hall, too, said it was a union representative who told him he needed to hire an attorney to help him file the workers’ compensation claims.

The network of attorneys and their hand-picked physicians who ushered him through the process was run like an assembly line and patronized by city workers of all stripes, Hall said: firemen, police officers, trash haulers.

His attorney, Julie Sherman of Straussner Sherman, referred him to several doctors with the assurance that they would “support your claim,” Hall said.

Sherman declined to comment.

There’s nothing unusual about what he did, Hall said, and he knows many other officers who have engaged in more strenuous physical activity while out with injuries.

He’s willing to speak out about the workers’ compensation abuse because he has nothing left to lose, Hall said. Other cops and firefighters who have been through the system won’t talk, he said, because doing so would “screw over a lot of their friends. It’s corrupt, and a lot of people do it.”

Garcia-Roberts is a former Times staff writer.

Twitter: @JackDolanLAT

Twitter: @ryanvmenezes

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.