Portrait emerges of Wendy Greuel campaign’s downfall

Wendy Greuel entered the race for mayor of Los Angeles with the formidable advantages of a front-runner.

She had amassed a huge political war chest, and independent campaigns were willing to spend millions more. She won the backing of the some of L.A.’s most powerful labor unions, but also of the Chamber of Commerce. Big names from opposite ends of the political spectrum — former Republican Mayor Richard Riordan and former Democratic President Clinton — would ultimately endorse her. She spoke inspirationally of becoming the city’s first female mayor.

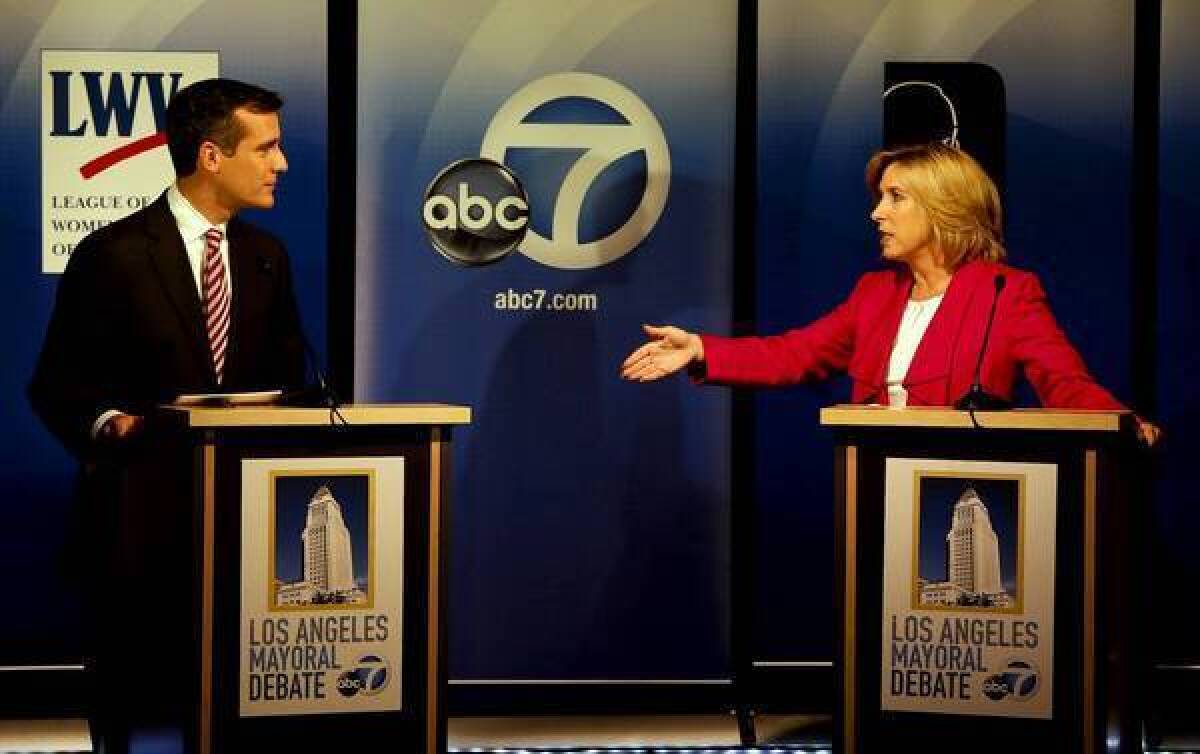

But six months after emerging as the leading candidate to succeed Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, Greuel’s campaign was handed a decisive defeat by her former City Council friend, Eric Garcetti. The portrait that emerges from interviews with campaign aides and analysts begins with a candidate who underestimated the strength of her opponents in the primary election and the importance of maintaining her brand as a trusted public servant. The slippage accelerated when Greuel’s efforts to promote past accomplishments and future goals drew new rounds of scrutiny and criticism. And attempts to take down her opponents fell short, according to the interviews with campaign operatives and outside experts.

The city controller and former City Council member who wanted to be ahead of the pack and run a positive runoff campaign highlighting her historic bid to become the city’s first female mayor found herself trailing and fighting a rear-guard action as voters went to the polls in March. After she finished 4 points behind Garcetti, key staffers departed, the financial advantages of employee-union backing became liabilities and her carefully cultivated reputation as a straight-shooting watchdog of the public purse suffered.

Greuel did not respond to a request for comment. But in recent days, reviewing the race with her closest advisors, she took solace in the fact that she fought hard for a job she had long coveted. Greuel repeated a quotation she had etched on her mother’s gravestone: “Unless a person sets out to do more than he can possibly ever do, he will never do all that he can.”

As she ramped up her campaign last year, Greuel believed that, as controller, she had built the perfect platform to run for mayor in a city that seemed perpetually in financial crisis, aides said. She would hammer at the $160 million in “waste, fraud and abuse” that the controller’s office calculated she had uncovered during more than 80 audits. She suggested she could use such savings to help balance the budget.

FULL RESULTS: L.A. election 2013

But Greuel’s team failed to delve deeply into the numbers buttressing the central theme of her campaign. Aides were caught off guard by the intensity of reporters’ challenges. The media wanted to know how much the candidate could recover for the city treasury, and her answers were vague.

Changing focus, Greuel rolled out an ambitious and costly plan to add 2,000 officers to the Los Angeles Police Department. Polls show strong voter support for public safety improvements, but prominent political and civic leaders attacked the idea, noting the city already had slashed services, including 911 medical response teams, to reach a 10,000-officer force.

Greuel then backed away from the proposal, stressing that adding 2,000 more cops was an “aspiration.” But the damage from questionable audit savings and criticism of her proposed police buildup had been done, said a source inside the campaign who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of discussing internal matters. “It just exploded the trust that Wendy had built with the voters.”

GRAPHIC: Contributions by special interest

Greuel and Garcetti appeared to be gliding toward a two-candidate runoff election from the start. But John Shallman, Greuel’s chief strategist, acknowledged last week that campaign officials underestimated the punishment their candidate was in for during the primary.

“We didn’t perceive Jan Perry or Kevin James as serious candidates in any way, shape or form,” Shallman said, referring to the strength of the veteran African American councilwoman and Republican former radio host. “That was a mistake.”

James, an attorney, was under-financed but particularly effective at withering sound bytes that attracted media coverage. He spoke with authority to conservative San Fernando Valley voters, who Greuel — a self-described “Valley girl” — long assumed would be a crucial pool of support. “Suddenly he became real,” Shallman said. “The more real he became, the more of a challenge it became for us to hold on to and compete for our base.”

James took the lead in warning voters of Greuel’s connections to city unions, particularly the one representing many Department of Water and Power workers, who spent nearly $1.7 million on an independent campaign to get her elected. The message appeared to stick, according to USC Price/LA Times polling.

Perry, meanwhile, launched a series of blistering mailers attacking Greuel, including one that accused her of being a closet Republican. (She had actually switched to the Democratic Party two decades ago.) Perry’s attacks appeared to be “almost a political suicide bombing,” Shallman said, more designed to take down Greuel than promote Perry’s candidacy. When Greuel retaliated with a mailer of her own — hitting Perry for a personal bankruptcy filing years earlier — women and African Americans accused Greuel of stooping to a lowly personal attack.

A string of nearly 50 debates before the March 5 primary also played away from Greuel’s strengths. She was charming and relaxed with small groups of voters, but she visibly stiffened going on stage for debates.

Garcetti was more polished, glib and less of a target than Greuel for the other primary election contenders, who saw more opportunity to siphon votes away from her.

Campaign aides began turning down debate invitations. But Greuel, determined to compete, would call back organizers and promise to participate.

A number of Greuel’s efforts to attack Garcetti failed to stick or blew up on her. She criticized him for taking taxpayer-funded trips, when she too had been on such trips. She attacked the number of city cars his office had, when as a council member her staff had the same number of vehicles.

To both insiders and political observers, the lack of precision had the hallmark of a low-profile race, such as an Assembly campaign, where press scrutiny is far less intense.

As the unexpected challenges of the primary election grew, trouble was brewing inside Greuel’s campaign. The bulk of her field team, responsible for identifying supportive voters and getting them to the polls, quit shortly after the March vote. Shifting to a new team left Greuel’s get-out-the-vote operation in catch-up mode.

Meanwhile, Shallman was clashing with Rose Kapolczynski, a veteran of Sen. Barbara Boxer’s campaigns, who had been hired early on to run day-to-day operations. Inside team Greuel, some saw Shallman as too aggressive. Others viewed Kapolczynski as too cautious. Kapolczynski decided she could no longer be part of the effort before the March primary, though she held off on leaving until after the March voting.

Raising the cash needed for a come-from-behind victory in the runoff became a major new obstacle after a USC Price/LA Times poll showed Greuel trailing Garcetti by 10 points.

The Greuel campaign took a gamble on a game-changing play that might close the gap, aides say. Greuel launched an early barrage of advertising, spending $1.7 million over two weeks in an effort to pull even. The airwaves were flooded with ads showing Magic Johnson, Riordan and Boxer singing Greuel’s praises. The move drained her coffers, but Greuel drew even with Garcetti in public and private polls.

But the flow of money did not return. In part, aides acknowledge, business donors were concerned by Greuel’s image as the candidate of city employee unions — and particularly the relatively high-paid workers at the city’s utility.

That left the Greuel campaign heavily dependent on the independent groups and “super PAC” committees that were backing her bid — and causing her problems in the polls and airing a muddy mishmash of ads on television.

Going into election day, Greuel staffers were nervous. Their early ad blitz hit just as voting by mail began. Greuel insiders figured they needed a five-point edge in the first big wave of mail-in ballots counted election night.

When the first tally appeared on a jumbo screen at Greuel’s election night party at a downtown nightclub, she was up by 2 points. Some guests cheered. But her campaign staff sensed where the night would end.

Garcetti gained ground with each new count, eventually winning by 8 points.

Greuel turned 52 two days after the election. She headed to Palm Desert, where she has spent every Memorial Day weekend since her teens with family and friends. She’d cut short her stay in recent years as she pursued her dream of being mayor. A friend said Greuel plans to enjoy the entire gathering this year.

“She can do the whole thing,” the friend said, “and she is having fun.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.