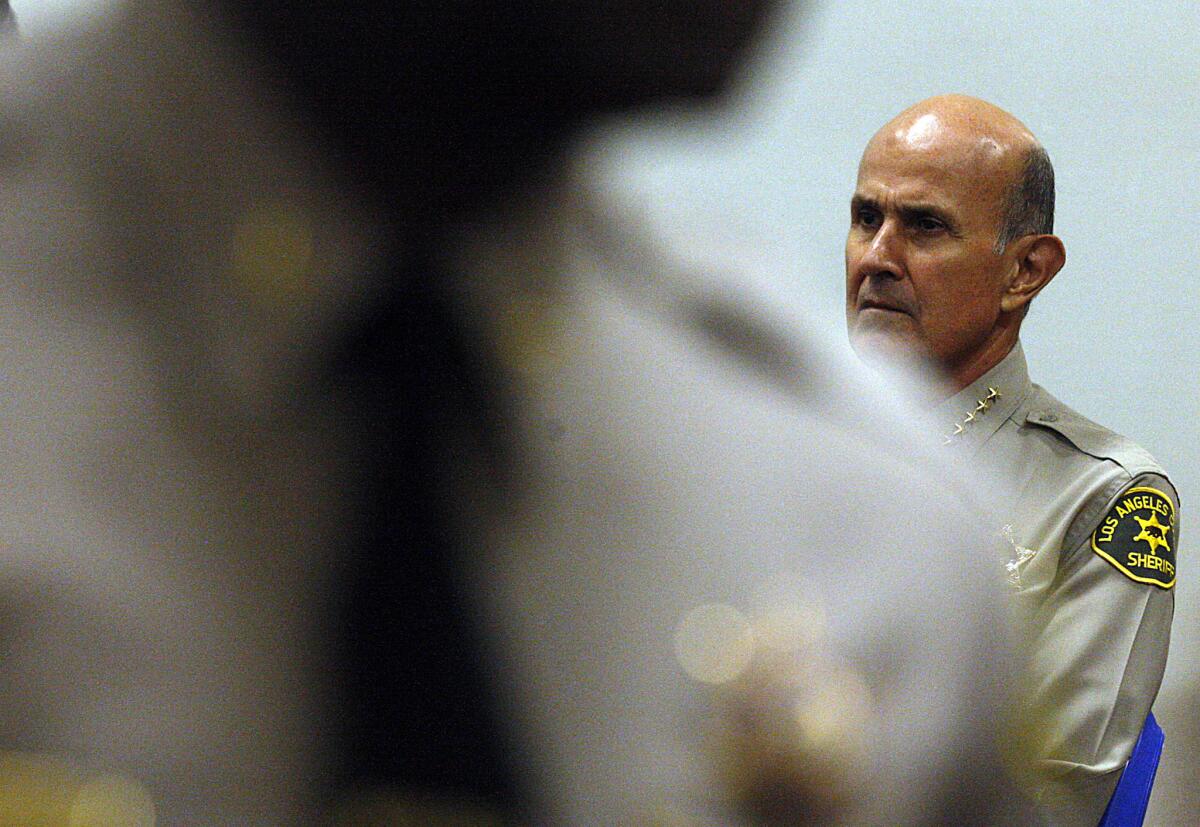

Baca nephew is subject of inmate abuse probe

When Justin Bravo applied to be a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy, background investigators noted the young man had some brushes with the law that raised red flags about his past.

Nonetheless, the department hired Bravo as a deputy through a little-known program called “Friends of the Sheriff” — a screening process for applicants with connections to department officials.

Bravo’s link was his uncle: Sheriff Lee Baca.

Now, the jail deputy is the subject of a Sheriff’s Department criminal probe into whether he abused an inmate. The incident, sheriff’s officials say, was caught on tape. Sources say FBI agents investigating the jails are also inquiring about Bravo.

Confidential sheriff’s records indicate that Bravo was hired even though officials had documented his alleged involvement in a fight with San Diego police, theft and arrests on suspicion of drunk driving and burglary.

Following inquiries from The Times, the Sheriff’s Department’s civilian monitoring agency looked at Bravo’s background. The Office of Independent Review’s lead attorney, Michael Gennaco, said in an interview “there is no way he should have been hired.”

Baca and Bravo, 32, declined to be interviewed. Bravo has been relieved of duty with pay in connection with the criminal probe.

This isn’t the first time that the hiring of an applicant with ties to a top sheriff’s official has drawn scrutiny. Last year, The Times reported that the son of the undersheriff’s secretary was hired as a security guard despite a history of theft, dishonesty, liaisons with prostitutes and as many as 100 domestic violence incidents. When he applied for the job, he was still on probation for punching a man unconscious.

In 2011, The Times reported that a recruit with ties to Baca’s son was hired during a hiring freeze for rookie deputies.

Baca’s spokesman, Steve Whitmore, said the sheriff was unaware of his nephew’s past and played no role in the decision to hire him in 2007. After inquiries from The Times, Baca asked the department’s official watchdog and internal investigators to review Bravo’s history to determine whether sheriff’s employees gave him special treatment.

Personnel records reviewed by The Times show that for years Baca’s department has operated a special hiring track for friends and relatives of department employees. The program was called FOS, or “Friends of the Sheriff” but is now operated under a different name, sources said. In 2009, the sheriff’s watchdog reviewed the hiring practice, calling the name “unfortunate,” but concluded that there was no evidence that those hired through the special track “routinely received preferential treatment during the background investigation process.”

At the time, the Office of Independent Review also said that the sheriff “knows virtually none of the individuals on the list” — that the list “might more aptly be titled ‘Applicants Who Know Someone on the Sheriff’s Department.’ ”

In a recent interview, Gennaco argued that having a separate hiring track for people who know sheriff’s officials actually helps prevent special treatment. After an FOS applicant’s background is investigated, he said, a final hiring decision is made by a special panel of commanders who are not informed of the applicant’s identity.

An internal sheriff’s spreadsheet reviewed by The Times shows Bravo was an FOS candidate, listed as “Sheriff Baca’s nephew” and noted as having a “459 arrest” — penal code for burglary — along with “DUI arrest, fight w/San Diego PD and theft.”

“The sheriff didn’t know anything about this,” Whitmore said.

Though Whitmore declined to discuss those allegations of misconduct in detail, he said “most of it occurred, if not all, while he was in the Marine Corps.” Military disciplinary records are not public, and The Times could not find court records indicating Bravo was charged. Whitmore said that arrests alone, without convictions, would not necessarily disqualify a job candidate.

The sheriff’s hiring rules give officials wide discretion. Some experts have said they allow for too much leeway, especially when it comes to evaluating serious misconduct such as lying, stealing and violence.

Concerns about Bravo’s conduct began early in his career. Retired sheriff’s Cmdr. Robert Olmsted told The Times that in about 2009, a sergeant caught Bravo looking at inappropriate material on a jailhouse computer. When confronted, Bravo yelled at the sergeant to mind his own business, Olmsted said. About a month later, Olmsted said, Bravo went to an off-duty party, where he ripped another deputy’s shirt pocket and fought with him. As he was being escorted out of the party, Olmsted said, Bravo was caught on tape acting belligerently and banging on countertops.

Anthony Brown, an FBI inmate informant, has told The Times that Bravo once smuggled him a cellphone behind bars — a claim a spokesman said sheriff’s detectives investigated but could not substantiate. In 2011, Brown was smuggled a cellphone by a deputy who didn’t realize Brown was secretly helping with the ongoing federal probe of the jails. Brown said he used that phone to communicate with his FBI handler on the outside. The transaction led to a bribery conviction against that deputy.

In an interview with The Times, Brown said that before he got that phone, another cellphone was smuggled to him by a second deputy: Bravo. He said that before the handoff, Bravo stripped him naked to make sure he wasn’t wearing a wire. Brown’s work has helped secure the conviction of one deputy, however court files and interviews reveal that he has previously made false allegations.

FBI agents investigating jailhouse misconduct have recently asked potential witnesses what they knew about Bravo, according to sources.

An FBI spokeswoman declined to comment.

Times staff writer Jack Leonard contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.