Los Angeles librarian is all over the maps

Glen Creason is used to waiting at the downtown Central Library. At the reference desk in a large space four floors below 5th Street, he knows the questions will come. They always do.

“There was a baseball field somewhere in L.A. in 1888 that only lasted one year. Where was it exactly?”

“How do I find the gravel pit where the Sleepy Lagoon murder took place?”

Creason has heard it all. “One I get constantly is, ‘Do you have maps of the secret tunnels dug under L.A.?’ .... They are secret tunnels and they do not appear on maps,” he says.

Amid the stacks of history and genealogy volumes, and the drawers of microfilm, Creason, 65, leaves no doubt about where his heart lies: maps.

Tall and affable, he has helped preserve a street-by-street history of Los Angeles.

“I love to answer map questions,” says Creason, who has worked at the Central Library for 32 years and became map librarian in 1989.

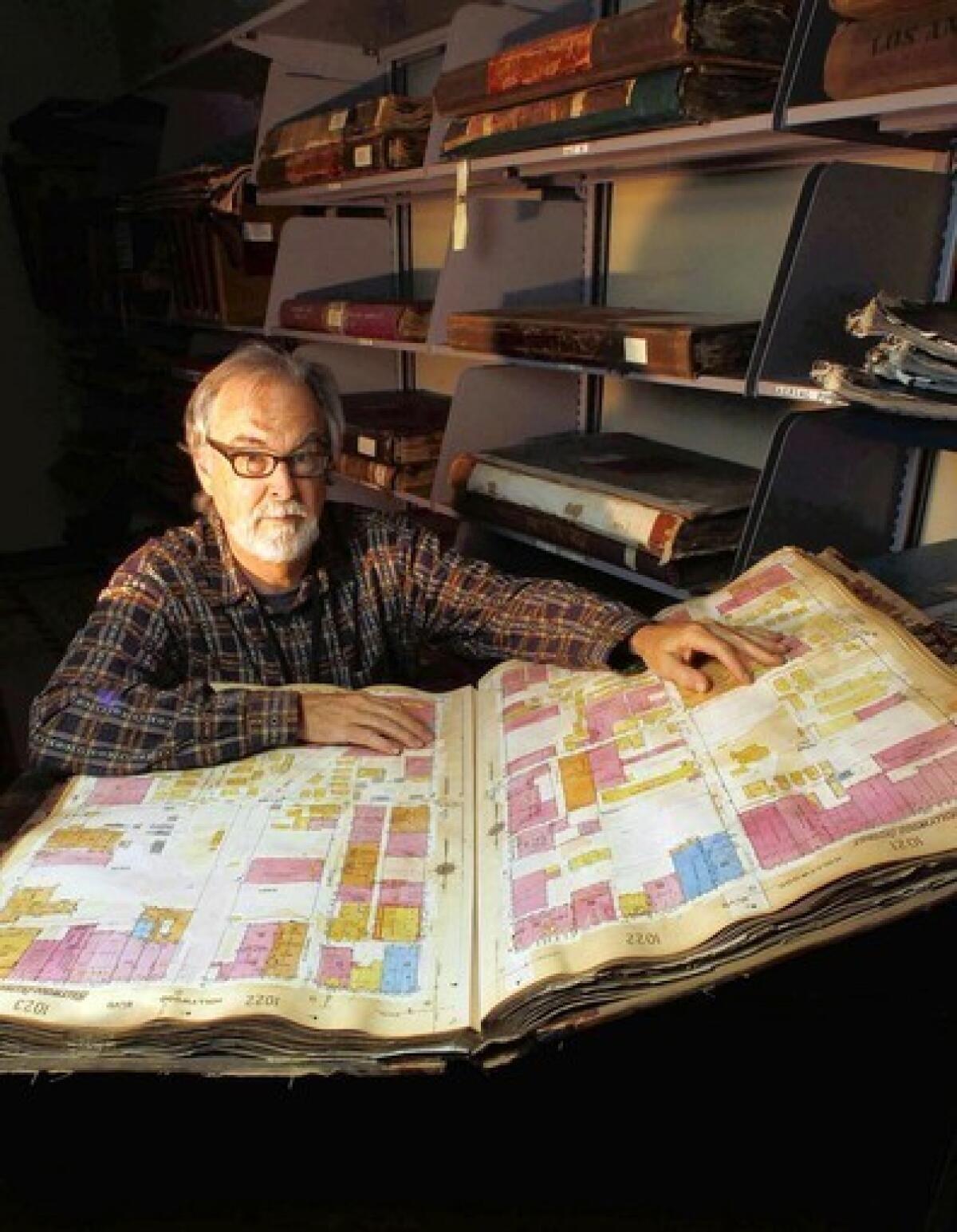

On a tour of some of the 100,000 maps in the library’s collection, Creason pulls out the large, heavy volumes of Sanborn maps — detailed drawings of each block of the city prepared for insurance purposes that are a trove of information about old L.A.

He also points out the one-sheet street maps given away by gas stations and real estate agents years ago, survey maps, souvenir maps of movie stars’ homes and pictorial maps, all snapshots of the city’s past.

There’s also what he calls the Ry Cooder map of Los Angeles, now hanging on a wall, which was used for the “Chavez Ravine” album.

Creason, author of “Los Angeles in Maps,” knew almost nothing about maps when he got the job. “At the first staff meeting that we had, one of the other librarians asked me what scale was and I didn’t know,” he says of the measurement on every map showing its ratio of distance, such as each inch equaling a mile.

A Los Angeles native raised in South Gate, Creason worked as a janitor, was a mail carrier in college, sold scientific equipment and made deliveries for his father, a ticket broker. “I got robbed at gunpoint and I decided I didn’t want to do that anymore,” he says.

“I used to spend a lot of time at the library in South Gate,” he says. “It helped that there were two beautiful librarians that worked there. Then on a whim I said, ‘Why not go to library school?’ ”

He graduated from Cal State Fullerton shortly before the passage of Proposition 13 in 1978, which diminished his chances of a job in the public sector, so he worked at the Herald Examiner library for two years until he was hired as a children’s librarian in San Dimas.

The Central Library in downtown Los Angeles was considered the big leagues.

“I had applied, just as a dream, because I always wanted to work in this building,” he says. He was hired in 1979 in the history department.

But the old library — before the 1986 fire — had some drawbacks.

“There was no air conditioning, there was really no heat,” he says. “It was completely unkempt and [had] almost no security. Ninety percent of the books were in closed stacks and had to be retrieved.”

The reference desk was hectic and nonstop too.

“When you hung the phone up it would ring again,” he says. “If you worked a night shift, you got a lot of drunks asking, ‘What’s the longest river in the world?’ ”

The fire changed everything. While the badly damaged building was being renovated, librarians were dispersed to warehouses or to a temporary home in the old Title Insurance and Trust Co. building on Spring Street.

The previous map librarian, dismayed at the disorder in the collection after it was moved to the temporary quarters, stepped down and Creason got the job. As he went through the collection, he started asking: “Why are these things sitting in drawers where nobody is ever going to see them? I just totally fell in love with pictorial maps.”

The maps inspired several exhibits and eventually led to his book, which includes Edward O.C. Ord’s 1849 survey, a photographic map of a model of the city as it was in 1881 and Jo Mora’s elaborate, whimsical 1942 map of the city and its history, which is one of Creason’s favorites.

Even the darker side of Los Angeles is reflected in its maps, Creason says, like deed covenants that excluded African Americans and a notice — intended for Okies fleeing the Dust Bowl in the 1930s — that people who don’t have money shouldn’t come to Los Angeles.

Ask a librarian about favorite books on Los Angeles, and you’ll get quite a list. Creason’s favorite is “Los Angeles: Epic of a City” by Lynn Bowman. His recommendations also include Carey McWilliams’ “Southern California: An Island on the Land,” the WPA Guide to Los Angeles, W.W. Robinson’s “Maps of Los Angeles” and lots of Raymond Chandler.

And after his years of studying maps, what has he learned?

“People always say, ‘Why is Los Angeles so spread out?’ and there’s so many reasons for that,” Creason says. “The streetcar lines were basically created by people who were going to make a lot of money selling real estate and that meant connecting everything that they could.

“These things that are reflected on these maps are either to make railways where you’re going to sell real estate along the path, you’re going to control water, you’re going to have movie studios, you’re going to sell the land to the rubes, and you portray Los Angeles as a garden.”

And after 32 years, Creason loves the Central Library as much as ever.

“The library always was like a dynamo for the city, the cultural heart of the city,” he says. “There aren’t the amount of phone calls we used to get because people think they can answer things with Google. But I can tell you, speaking for every librarian in this building, we wish they would call us more.”

He’ll be waiting.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.