Immigrant Marine in life, U.S. citizen in death

CAMP PENDLETON — Marine Cpl. Roberto Cazarez applied for U.S. citizenship shortly before he deployed for combat duty in Afghanistan.

The expedited process allows enlistees who are permanent legal residents, like Cazarez was, to go to the head of the line for citizenship.

Cazarez’s application was pending at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services when he was killed by a roadside bomb blast in March, just weeks before his battalion was due to return to Camp Pendleton.

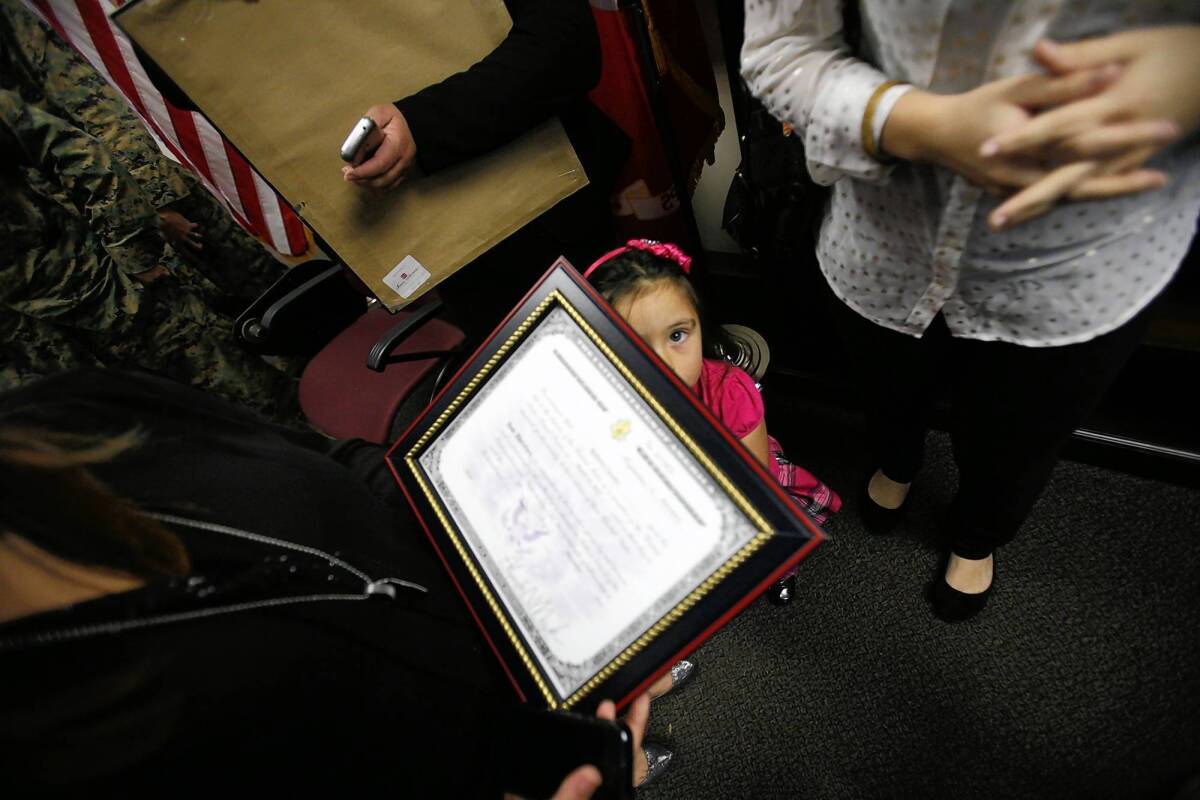

On Thursday, in a short but emotional ceremony, Cazarez’s widow was presented with a certificate indicating that her husband had been posthumously awarded his U.S. citizenship, retroactive to the day that he was killed.

Cazarez, who was 24 when he died, is the 144th military service member to be posthumously awarded citizenship since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks — more than in any other period of U.S. combat, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Of the 144, 139 had served during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan: 100 from the U.S. Army, 32 from the Marine Corps, six from the Navy and one from the National Guard.

Fellow Marines remembered Cazarez for his work as a driver in the 1st Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion, a unit assigned to roam the rugged desert of southern Afghanistan, locate Taliban fighters and engage them in direct combat.

“He was one of the most motivated Marines I’ve ever known,” said Cpl. Bryant Nobles, who served with Cazarez in Afghanistan. “If there was hard duty or heavy lifting to be done, he volunteered and never complained.”

The ceremony was also an opportunity for officials to note the historic role of immigrants in the armed forces. According to the Pentagon, 35,000 noncitizens are on active duty and 12,000 serve in the Guard or Reserves.

“The U.S. military is built on a legacy of immigrant bravery,” said Col. Michael Richardson, who represented the Marine Corps at the ceremony.

In some cases, posthumous citizenship can help surviving relatives seek entry into the United States. But that is not the case for Cazarez, whose family members are long-time U.S. residents with legal status, officials said.

Sonia Cazarez, 24, who is studying accounting at Saddleback College in Mission Viejo and living in Dana Point, said she sought citizenship for her husband because it was his last wish before deploying. She wears his ring and his dog tag on a chain around her neck.

“This really helps,” she said, her voice breaking with tears. “With all the grief, it’s nice to see people honoring him for what he did as a Marine.”

Cazarez came to the United States from the Mexican state of Sinaloa as a child. A permanent legal resident, he enlisted in the Marine Corps in 2006, days after graduating from high school in Harbor City. He was on his second enlistment, his first combat tour.

“He came here as a baby and knew very little about Mexico; he always considered himself an American,” Sonia Cazarez said. “That’s why this is so special.”

In the months after Sept. 11, as U.S. involvement in Afghanistan escalated, President George W. Bush signed an executive order declaring that a “time of conflict” existed, allowing him to authorize the expedited citizenship process for service members. Since then, more than 83,000 military personnel have become U.S. citizens, more than 10,000 of them while stationed overseas.

To enlist in the military, someone must already be a permanent legal resident of the United States. When the expedited citizenship process is in effect, the three- or five-year waiting period for citizenship is waived for military personnel.

Before he deployed to Afghanistan, Cazarez also encouraged a nephew to enlist. Francisco Yahuaca, 18, is in boot camp in San Diego.

“We’re a Marine family now,” Sonia Cazarez said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.