As wildfires get wilder, the costs of fighting them are untamed

LIVE OAK COMMAND POST — It was Day 42 of the Zaca Fire. A tower of white smoke reached miles into the blue sky above the undulating ridges of Santa Barbara’s backcountry.

Helicopters ferried firefighters across the saw-toothed terrain and bombed fiery ridges with water. Long plumes of red retardant trailed from the belly of a DC-10 air tanker. Bulldozers cut defensive lines through pygmy forests of chaparral.

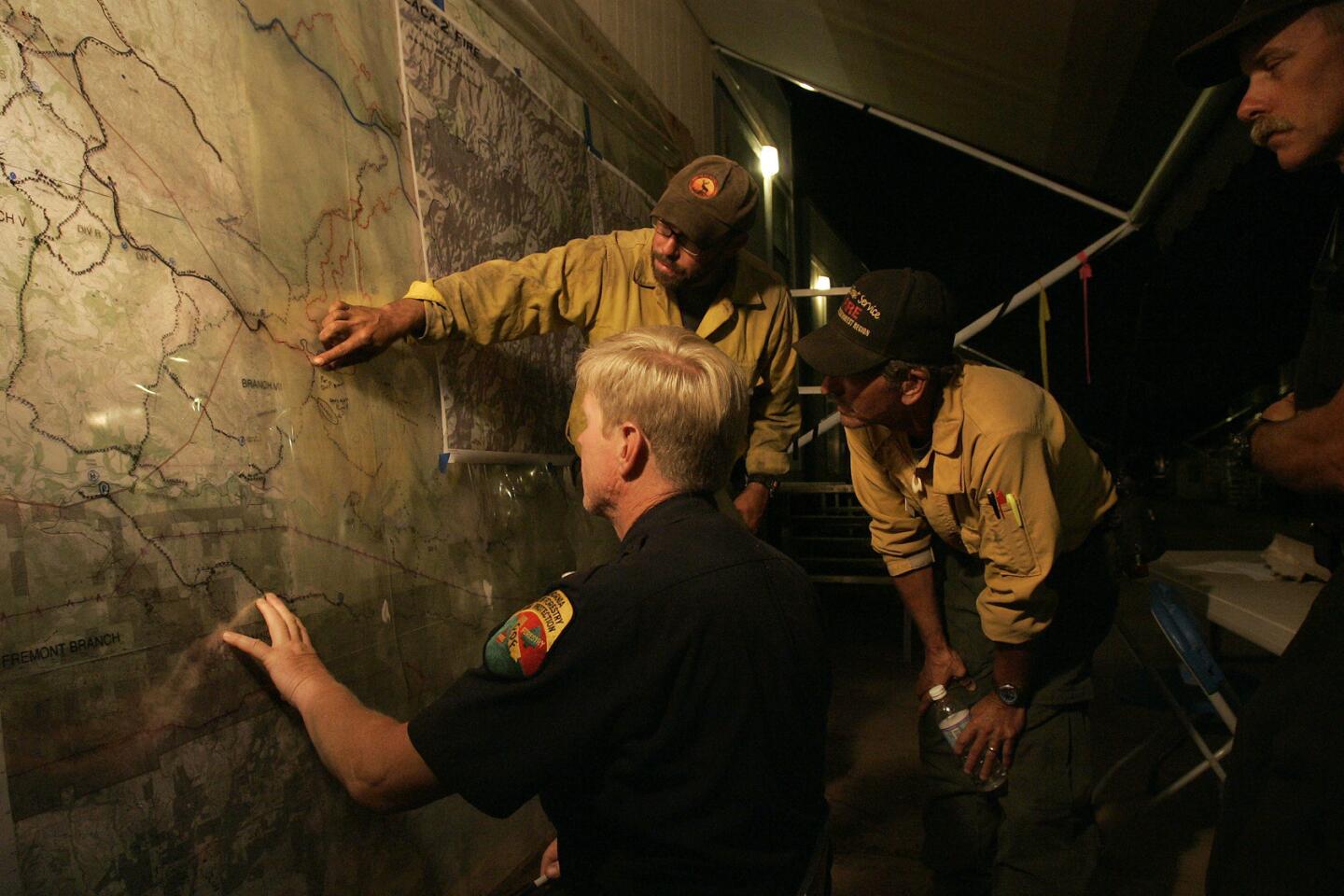

A few miles south, in a camp city of tents and air-conditioned office trailers, commanders pored over computer projections of the fire’s likely spread, trying to keep the Zaca bottled up in the wilderness and out of the neighborhoods of Santa Barbara and Montecito.

Platoons of private contractors serviced the bustling encampment, dishing out hundreds of hot meals at a time from a mobile kitchen, scrubbing 500 loads of laundry a day, even changing the linens in sleeping trailers.

On this single day, Aug. 14, fighting the Zaca cost more than $2.5 million. By the time the blaze was out nearly three months later, the bill had reached at least $140 million, making it one of the most expensive wildfire fights ever waged by the U.S. Forest Service.

A century after the government declared war on wildfire, fire is gaining the upper hand. From the canyons of California to the forests of the Rocky Mountains and the grasslands of Texas, fires are growing bigger, fiercer and costlier to put out. And there is no end in sight.

Across the country, flames have blackened an average of 7.24 million acres a year this decade. That’s twice the average of the 1990s. Wildfires burned more than 9 million acres last year and are on pace to match that figure in 2008.

At 240,207 acres, the Zaca was the second-biggest wildland blaze in California’s modern record. But nationally, it wasn’t even the largest of 2007. A conflagration on the Idaho-Nevada border charred more than twice as much land.

In response, firefighting has assumed the scale and sophistication of military operations. Consider the forces massed against the Zaca that sweltering August afternoon: nearly 2,900 federal, state and local firefighters, 122 fire engines, 35 bulldozers and a small air force of 20 helicopters and half a dozen air tankers.

Private contractors are taking on a major role in the nation’s wildfire battle, supplying much of the equipment, most of the camp services and even some firefighting crews.

Wildfire costs are busting the Forest Service budget. A decade ago, the agency spent $307 million on fire suppression. Last year, it spent $1.37 billion.

Fire is chewing through so much Forest Service money that Congress is considering a separate federal account to cover the cost of catastrophic blazes.

In California, state wildfire spending has shot up 150% in the last decade, to more than $1 billion a year.

“We’ve lost control,” said Stephen J. Pyne, a professor of life sciences at Arizona State University and the nation’s preeminent fire historian.

This “ecological insurgency,” as Pyne calls it, has varied causes. Drought is parching vegetation. Rising temperatures associated with climate change are shrinking mountain snowpacks, giving fire seasons a jump-start by drying out forests earlier in the summer. The spread of invasive grasses that burn more readily than native plants is making parts of the West ever more flammable.

The government’s long campaign to tame wildfire has, perversely, made the problem worse.

By stamping out most wildland blazes as quickly as possible, the Forest Service has stymied nature’s housekeeping -- the frequent, well-behaved fires that once cleaned up the pine forests of the Sierra Nevada and the Southwest. Now, woodlands are tangled with thick growth and dead branches. When fires break out, they often explode.

Firefighters still manage to snuff out the vast majority of wildfires in their early days. But the 2% to 3% that break away are “more aggressive and more difficult to contain and bigger and badder every year,” said Dave Bartlett, fire management officer for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.

Year after year, development relentlessly throws more homes into this combustible mix, escalating property losses and raising the political stakes.

From 1990 to 2000, 61% of the housing built in California, Oregon and Washington -- more than 1 million homes -- rose in or at the edge of fire-prone wildlands, according to a University of Wisconsin study.

Together these trends promise more fire and more high-priced firefights.

“There are three things that are driving it: climate, development, fuel loads.. . . . And they’re all unequivocally going in the wrong direction,” said Geoffrey Donovan, a Forest Service researcher in Portland, Ore. “I don’t see how anybody could think we’re anywhere close to being at the worst of this.”

Big fire has become big business. Roughly 60% of the Forest Service’s wildfire expenditures last year -- including firefighting, training and fuel reduction projects -- went to the private sector.

Contractors large and small provide a wide range of equipment and services on wildfires, including aircraft, ambulances, earthmovers, water trucks, even portable air-traffic-control towers and their operators.

Fire spending is helping prop up rural economies. Whether it’s renting California ranchland to stage heavy equipment or paying a dusty roadside cafe in Nevada to slap together hundreds of sack lunches for fire crews, the government is showering the West with fire money.

“Fire is becoming a kind of cash crop,” said Preston Wright, 50, a Nevada rancher and former head of the Nevada Cattlemen’s Assn. “When the firefighters show up, there are dollars along with them.

“If you talk to townspeople, they’ll say it was a good summer. They had a fire. It saved their summer.”

When the Charleston Complex fire raced across northeastern Nevada in 2006, the government leased the airstrip on Wright’s ranch for a helicopter base, paying him $1,000 a day for five days.

“That’s the way it is,” Wright said. “It brings this almost wartime funding machine into place.”

Spawned by sparks

On the morning of July 4, 2007, ranch hands were fixing a water pipe on private land in a narrow canyon off the road to Zaca Lake, about 15 miles north of Solvang.

The temperature was headed toward 100 degrees. Rainfall the previous winter had been among the lowest on record in Southern California. Sparks from a metal grinder jumped into some dry grass. Soon flames were rushing through the brush toward Zaca Ridge.

By the next day, nearly 1,000 firefighters were trying to box the fire into a small area. But late that afternoon, the Zaca made a run, moving east into Los Padres National Forest. By July 7, Forest Service officials realized they were facing a potential monster.

Los Padres is one of the most forbidding places on the West Coast to battle a wildfire. The terrain is folded and twisted into razorback ridges and steep canyons. Much of it is cloaked in dense chaparral that burns with ferocious intensity.

The Zaca was headed into the national forest’s San Rafael Wilderness -- jagged, road-less country that offered few places where firefighters could safely make a stand.

Bordering Los Padres to the south is a coastal stretch with some of the most valuable real estate in the country, something the federal commanders who managed the firefight never forgot.

Crews came close to corralling the Zaca at the end of July. For days, it was docile. Hundreds of firefighters were sent home. Then, on July 28, the fire jumped across a ridge on its southeast flank. Commanders called their troops back.

Single-digit humidity and 100-degree-plus temperatures in August sent whorls of flame more than 100 feet into the air. The brush was so dry “it was dead and didn’t know it,” said Bill Waterbury, a Forest Service official who oversaw the Zaca battle for three weeks.

Wildfires usually take a nap at night. The Zaca kept going. When it stalled on rocky mountaintops for lack of brush to incinerate, embers would roll into neighboring canyons, igniting more chaparral. Flames like to run uphill. The Zaca sometimes burned downhill against up-canyon winds. “I saw fire behavior I’ve never seen,” said Tom Hatcher, a retired Forest Service official who takes temporary fire assignments and served as a supervisor on the Zaca.

The fire bosses had more on their minds than rough terrain and a stubborn adversary. As more of the West is scorched, wildfires are being fought in a pressure cooker of public and political expectations. “You get the media pressure. The homeowners calling, elected officials calling,” said Scott Vail, a retired Forest Service incident commander in California. “Political people have to get in and say, ‘We’re doing everything we can.’ ”

On Aug. 3, the Zaca sprinted toward Santa Barbara, pumping out giant clouds of smoke and showers of ash. By coincidence, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger flew to the area that day to visit a friend. He took a detour to the Santa Barbara County emergency operations center, arriving just as county supervisors were meeting to declare an emergency.

“The county administrator was reading the proclamation, and somebody came in and whispered to me, ‘The governor is in the parking lot,’ ” Supervisor Brooks Firestone recalled. “While we were having our meeting, he was looking at the big cloud over the hill and talking to his office.”

There and then, Schwarzenegger signed a state proclamation of emergency, officially making the Zaca battle a California priority.

The next day, an additional 740 firefighters were on the scene.

By mid-August, the Zaca had burned into its second month and was less than 10 miles from Santa Barbara. Calls to the Forest Service picked up. Residents wanted an end to smoky skies and daily anxiety, and a Montecito woman was ready to do her part.

“She wants this fire to stop and is willing to provide resources ($) to make it happen,” reads the entry in a Forest Service phone log. “She doesn’t care about the fires across the nation. She feels this area must be protected and the fire put out.”

Creature comforts

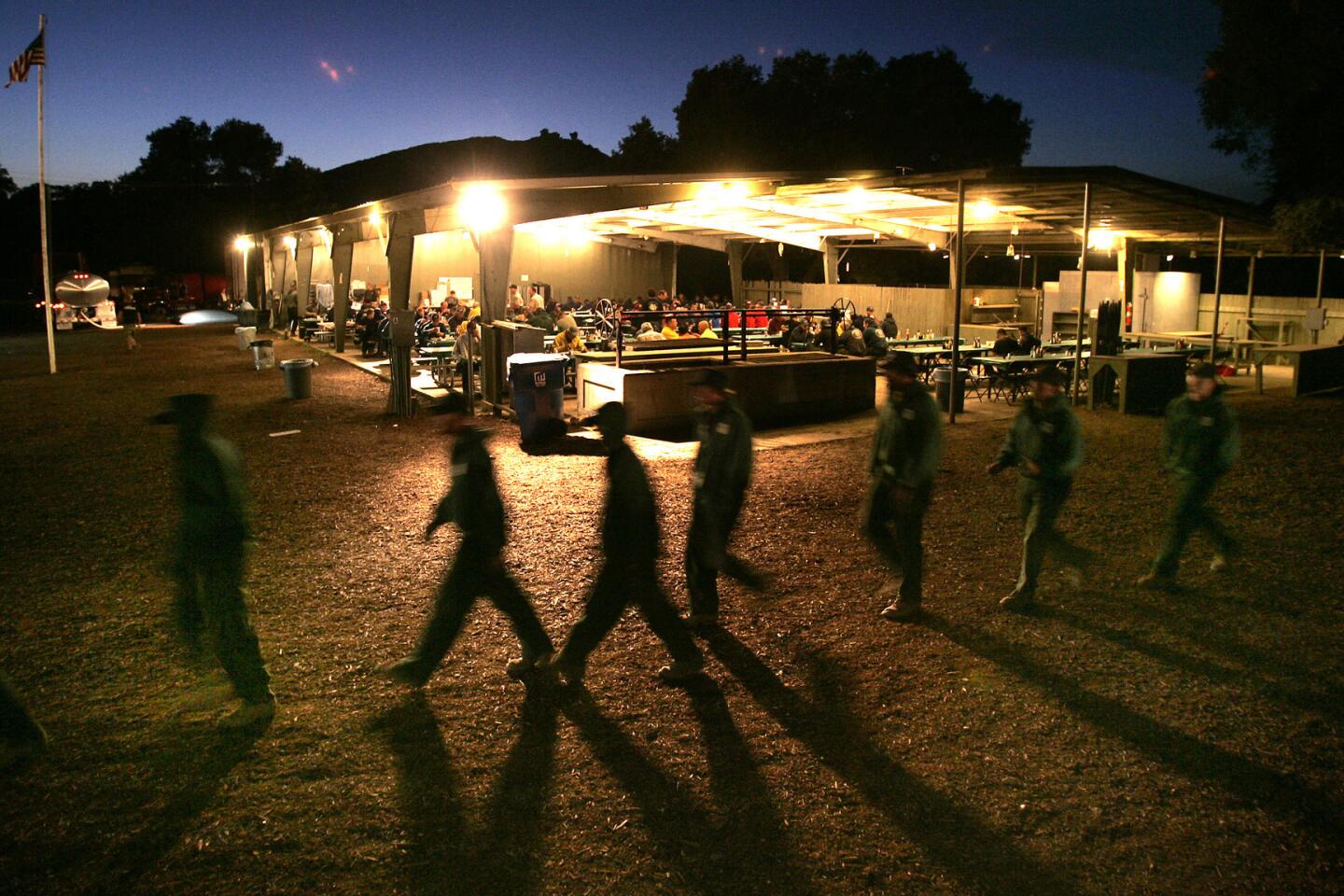

On Aug. 21, the Zaca army reached a peak of 3,100 firefighters from across the West.

Most of them ate, slept and got their orders in two elaborately equipped camps on either side of Los Padres.

When Lee Belau started out in the 1950s, fire camps were primitive.

“I remember the biggest improvement was when they got tables with chairs so you could sit down to eat,” said Belau, a retired Forest Service fire management officer who lives in Porterville.

“The toilets were a slit trench in the ground. . . . You slept on the ground. There were no tents.”

There were no showers either. Meals were cooked by inmate crews.

Forest Service financial records from the Zaca fire reveal just how much things have changed.

Not only did firefighters have tents, some of them retired to private berths in sleeping trailers supplied by the Mobile Sleeper Co. of Corona for $1,982 a day each. Each berth had its own temperature controls. Sheets were changed by an attendant.

Fire crews scrubbed down in 12-stall shower trailers that cost $2,100 a day. The gray water was hauled away in $1,667-a-day trucks.

A $400-an-hour mobile laundry washed their sooty clothes.

A mobile kitchen, run by an El Segundo company that caters movie shoots, served scrambled eggs and hot cakes for breakfast, curried chicken and barbecue ribs for dinner. For vegetarians, there was curried tofu or veggie fajitas.

The firm, For Stars Catering, grossed $4.7 million on the Zaca, according to Forest Service records.

A mobile copy center run by Michelle’s AAA Equipment Rentals of Riverside spit out tens of thousands of pages of documents every day, including the crew leaders’ bible: the “incident action plan” containing assignments, operations maps and safety information.

Fire bosses tracked the Zaca’s march across Los Padres with heat maps beamed from an infrared camera mounted on reconnaissance aircraft. They used software that calculated potential building losses if the fire burned unchecked in various directions.

Federal planners, contracting officers and public information specialists set up shop in camp. The Forest Service even sent an “incident business advisor,” an accountant whose job was to suggest ways to hold down costs.

They all worked in a “camp in a box” supplied by Western Fire Support Systems for $13,650 a day. It included 10 air-conditioned office trailers with Internet connections, generators, floored tents and a hand-washing unit with 12 sinks and hot water.

Dan Anglin, a former Tehachapi firefighter, runs Western Fire with his wife out of the Lake Isabella area. They got into the fire camp business two decades ago with a portable laundry and now have $1 million worth of equipment. They call themselves “comfort specialists.”

Between the Zaca and last fall’s Southern California wildfires, 2007 was the company’s best year ever. Anglin said he grossed more than $1 million.

As the Zaca dragged on, the Forest Service dispatched buying teams to keep the army of firefighters and its attendant bureaucracy stocked with everything from mouse pads to Kleenex.

Shoppers stayed in motels outside the fire zone, drove rental cars and spread across Santa Barbara and adjacent counties with their federal credit cards, charging more than $2 million worth of supplies at big-box stores and out-of-the way country marts.

At the Sports Authority in Goleta, they loaded up on $527 worth of anti-blister sticks.

At a Vons they bought $650 worth of grapes, pears, plums, nectarines, peaches and organic pluots in a single day.

At the Office Depot and Staples stores in Santa Maria, they piled copy paper, printer toner and canned air into shopping carts. When firefighters complained of being eaten alive by bugs at a riverside camp, the buyers ordered netting from a Sacramento beekeeper.

To protect historic ranch buildings scattered around Los Padres, they ordered 66 rolls of a fire-resistant aluminized wrap for $34,000. Swathed in shining fire shields, the buildings looked like Christmas presents for King Kong.

On the fringes of Los Padres, federal contracting officers fanned out to find ranch and farm land where the Forest Service could -- for a price -- stage equipment and draw water.

Ozena Valley Rock & Sand, a family-owned farm and mining operation on 2,200 acres on the east side of the fire, made $5,000 a day.

Helicopters dipped their buckets into the ranch’s spring-fed reservoir, and water trucks filled up around the clock.

The Forest Service set up a refueling station, parked heavy equipment and pitched firefighter tents around the ranch.

Anthony Virgilio, who owns the mining operation with his mother and brother, said they shut the business during the weeks of fire activity, but took in enough money -- $185,000 -- to keep their five full-time employees on the payroll.

In the deeply creviced mountains of Los Padres, much of the firefight itself was waged with private equipment.

Like giant bumblebees gathering pollen, $3,203-an-hour helicopters gulped water from mountain reservoirs and $1,796-a-day portable dip tanks. Smaller choppers costing $1,617 an hour flew supplies and fire crews to remote areas.

Contractors ran $2,461-a-day bulldozers through the chaparral to clear fire lines and chewed up brush with $200-an-hour masticators. To meet air-quality regulations and protect sensitive equipment, they wet the ground with $1,671-a-day water trucks to control dust.

Tom Nason drove down to the Zaca in July from Ventana Wilderness Ranch, his cattle and vineyard operation in Big Sur. He brought along a dozen employees, two 4,000-gallon water trucks and two flatbeds loaded with bulldozers.

Nason and his crew spent more than two months bulldozing fire lines, hauling heavy equipment and doing other work.

They were gone so long that Nason had to hire extra hands back home. He grossed about $250,000 on the Zaca, one of six California wildfires his men worked last summer.

Nason’s family, descendants of Big Sur’s Esselen Indian Tribe, has been trucking heavy equipment to wildfires since the 1960s. In the last decade, there has been such a surge in demand that Nason is buying another bulldozer and water truck and starting a separate business, Ventana Fire, to handle it.

“I got called 28 times last year. I wasn’t able to keep up,” he said. Half his income now comes from wildfires.

The Forest Service says it’s cheaper in the long run to contract for private equipment on a fire-by-fire basis than to own it and pay for year-round salaries and maintenance.

“I don’t know of many businesses that would go out and get something, pay for it just to stand by, when they can readily get it for the times they need it and then let it go,” said Sue Prentiss, a Forest Service branch chief who oversees contracting from the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise, Idaho.

“If the commercial sector can provide it, why not?”

A 2005 federal audit found that the Forest Service risked fighting fires with “marginal equipment from substandard vendors” because its emergency rental system lacked competitive pricing and adequate contractor evaluations.

The agency pays fixed rates for much of the equipment and services it uses on fires. Only now, as a result of the audit, is the Forest Service beginning to seek competitive bids.

In early September, when the Zaca fire was on the wane, dispatchers called Josh Smith in Battle Mountain, Nev., and asked him to send a firetruck with a three-man crew to help with mop-up.

Smith, a 32-year-old alfalfa farmer, got his start in wildfires in 1999, when the federal Bureau of Land Management was “pretty much begging just anybody to help” stop brush and grass fires that raged across northern Nevada that summer.

He answered the call with his farm equipment, using tractors and plow discs to cut fire lines. The next year he outfitted a pickup truck with a tank, hose and reel. Soon he was being dispatched to blazes all over the West.

He calls his two-engine enterprise Smokin’ 75 and hires college students and handymen as seasonal crews. Smith, who grossed $34,230 on the Zaca, makes more money from fire than from his 200 acres of alfalfa.

“If I wasn’t to have the firetruck, I wouldn’t be able to afford to farm.”

Fighting fire with fire

Ultimately, the Zaca battle was shaped by the threat of a firestorm blasting out of the back- country, down the Santa Ynez Mountains and into a major transmission line and billions of dollars’ worth of real estate.

Dozens of engine crews were stationed at the Earl Warren Showgrounds in Santa Barbara, staying in motels on the public tab, ready to defend neighborhoods if flames shot over the mountains.

Commanders ordered defenses built on the steep southern flanks of the blaze -- a series of fire lines cut through thick chaparral.

Bulldozers cleared some of them. Where the roller-coaster terrain was too dangerous for heavy equipment, firefighters attacked the brush with hand tools and chainsaws. Helicopters and air tankers dropped water and retardant to slow the fire’s southward progress.

Crews were herding the fire to the east, toward Highway 33, where they hoped to stop it at last.

In the dense wilderness that lay in the Zaca’s path, they lighted huge backfires that raged for days, charring tens of thousands of acres. When the main front reached this blackened expanse, it had nowhere to go.

Fire finally conquered the Zaca.

It was declared contained Sept. 2, two months after it began. Pockets continued to burn into November.

In the end, no lives were lost and just one structure -- a shed -- was destroyed.

Rich Hawkins was in charge when the Zaca was halted. One of an elite team of national incident commanders for the Forest Service, he is used to long, tough fights. But the Zaca stood out.

“I’ve never spent so much taxpayer money,” he said months later. “That’s what it took to protect the communities.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.