Farmworkers Reap Little as Union Strays From Its Roots

Red letters flash inside the famous black eagle, symbol of the United Farm Workers: “Donate,” the blinking message urges, to carry on the dreams of Cesar Chavez.

Bannered on websites and spread by e-mail, the insistent appeals resonate with a generation that grew up boycotting grapes, swept up in Chavez’s populist crusade to bring dignity and higher wages to farmworkers.

Thirty-five years after Chavez riveted the nation, the strikes and fasts are just history, the organizers who packed jails and prayed over produce in supermarket aisles are gone, their righteous pleas reduced to plaintive laments.

What remains is the name, the eagle and the trademark chant of “Sí se puede” (“Yes, it can be done”) — a slogan that rings hollow as UFW leaders make excuses for their failure to organize California farmworkers.

FOR THE RECORD:

UFW —A series last month on the United Farm Workers contained three factual errors about the history of the labor union and its related organizations. Health clinics operated during the 1970s were run by the UFW-affiliated nonprofit National Farm Workers Health Group, not the union directly, as reported Jan. 8. UFW officials said that a Fresno developer who partnered with Cesar Chavez to build for-profit housing donated his services and did not split the profits from the developments, as reported Jan. 9. And UFW officials said a school bus abandoned in a back field at union headquarters was not one of the buses used to transport boycott volunteers across the country in the 1970s, as stated in the Jan. 9 article, but was left by a peace activist who never returned to claim it. In addition, the Jan. 8 article reported that the UFW “board deleted all specific references in the UFW constitution to agricultural workers, including the preamble.” To clarify: The board deleted the entire preamble and amended the constitution to include all categories of workers, so that the UFW constitution no longer applied only to agricultural workers and related laborers.

Today, a Times investigation has found, Chavez’s heirs run a web of tax-exempt organizations that exploit his legacy and invoke the harsh lives of farmworkers to raise millions of dollars in public and private money.

The money does little to improve the lives of California farmworkers, who still struggle with the most basic health and housing needs and try to get by on seasonal, minimum-wage jobs.

Most of the funds go to burnish the Chavez image and expand the family business, a multimillion-dollar enterprise with an annual payroll of $12 million that includes a dozen Chavez relatives.

The UFW is the linchpin of the Farm Worker Movement, a network of a dozen tax-exempt organizations that do business with one another, enrich friends and family, and focus on projects far from the fields: They build affordable housing in San Francisco and Albuquerque, own a top-ranked radio station in Phoenix, run a political campaign in support of an Indian casino and lobby for gay marriage.

The current UFW leaders have jettisoned other Chavez principles:

The UFW undercut another union to sign up construction workers, poaching on the turf of building trade unions that once were allies.

The UFW forfeited the right to boycott supermarkets and stores, a tactic Chavez pioneered, in order to sign up members in unrelated professions.

And Chavez’s heirs broke with labor solidarity and hired nonunion workers to build the $3.2-million National Chavez Center around their founder’s grave in the Tehachapi Mountains, a site they now market as a tourist attraction and rent out for weddings.

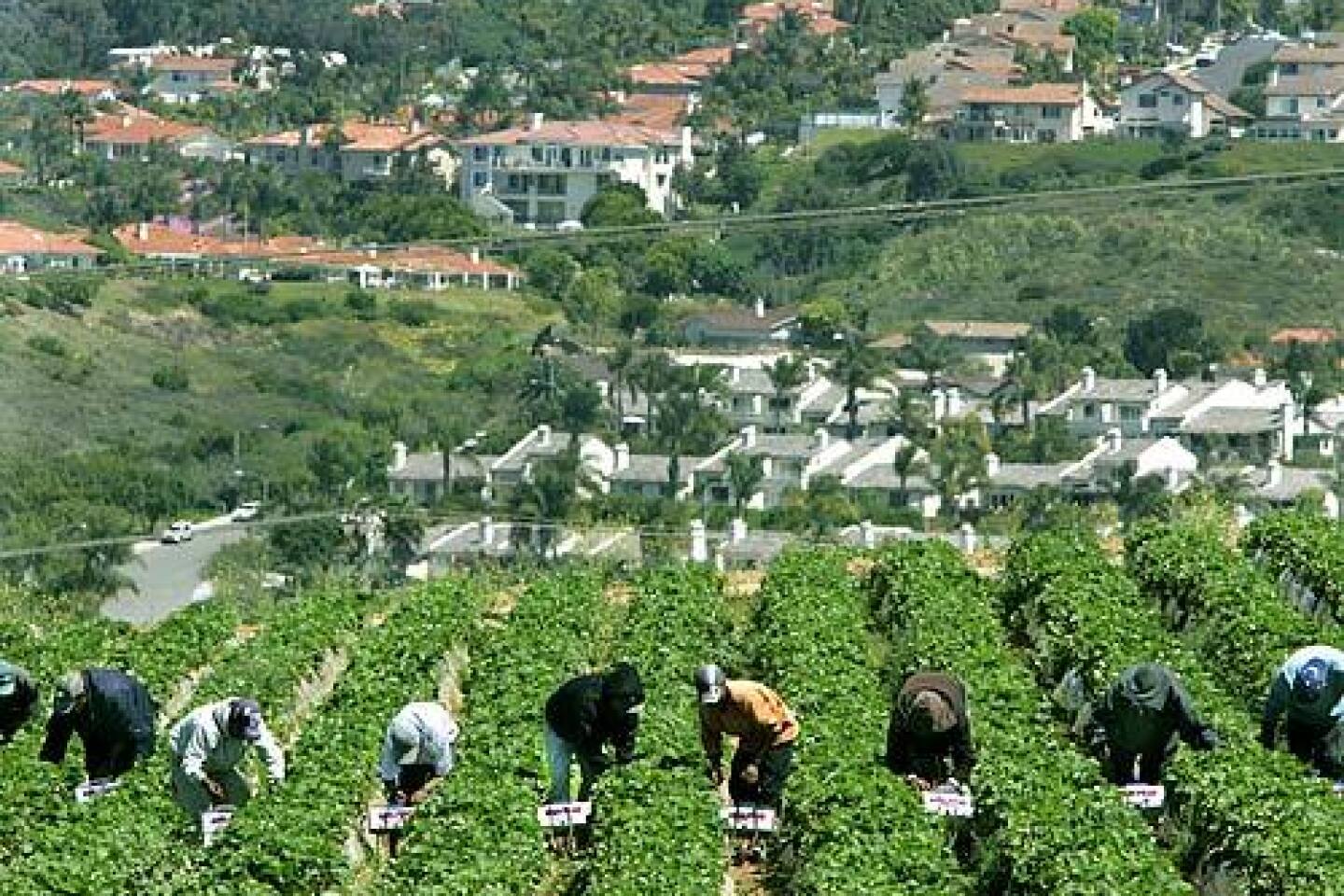

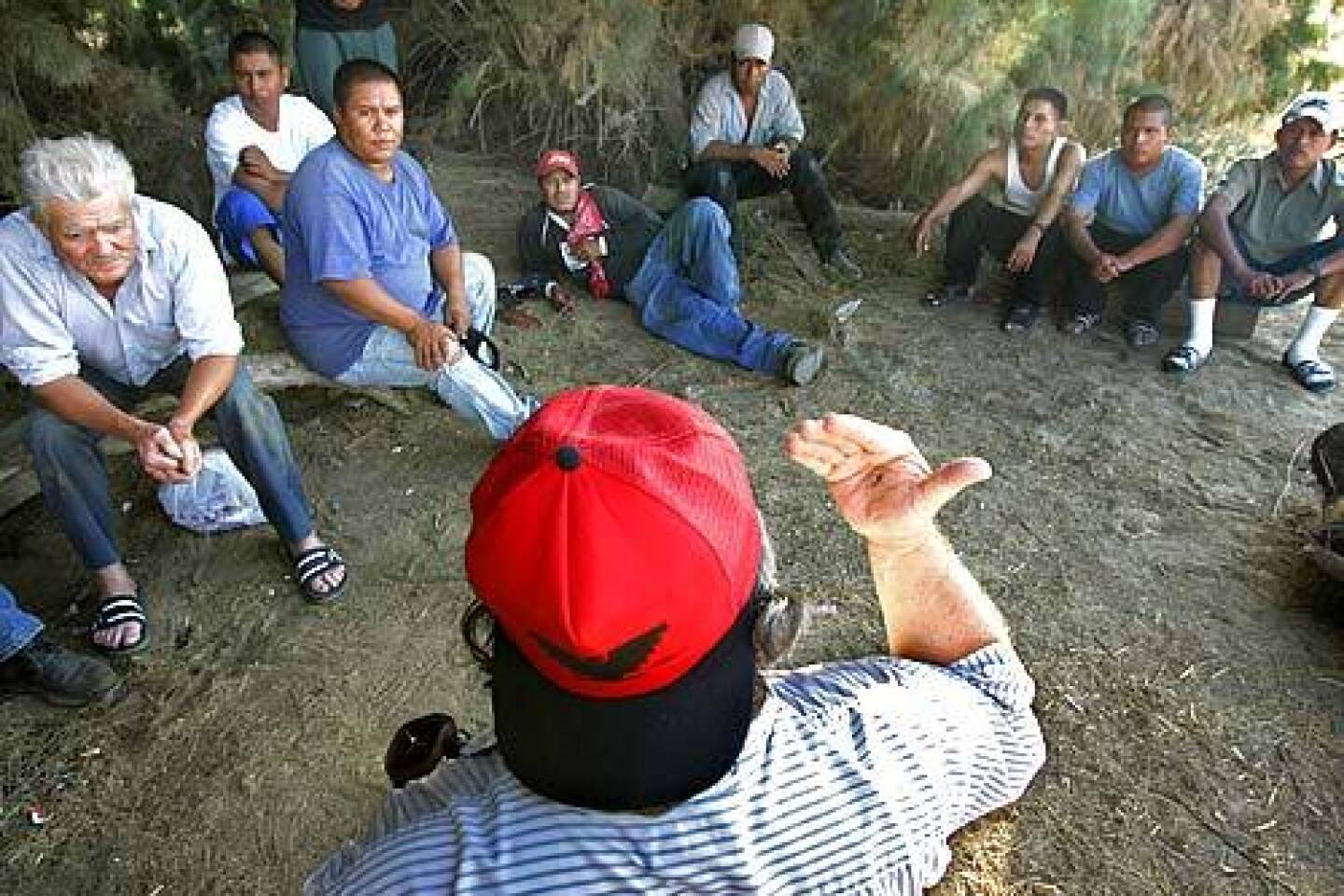

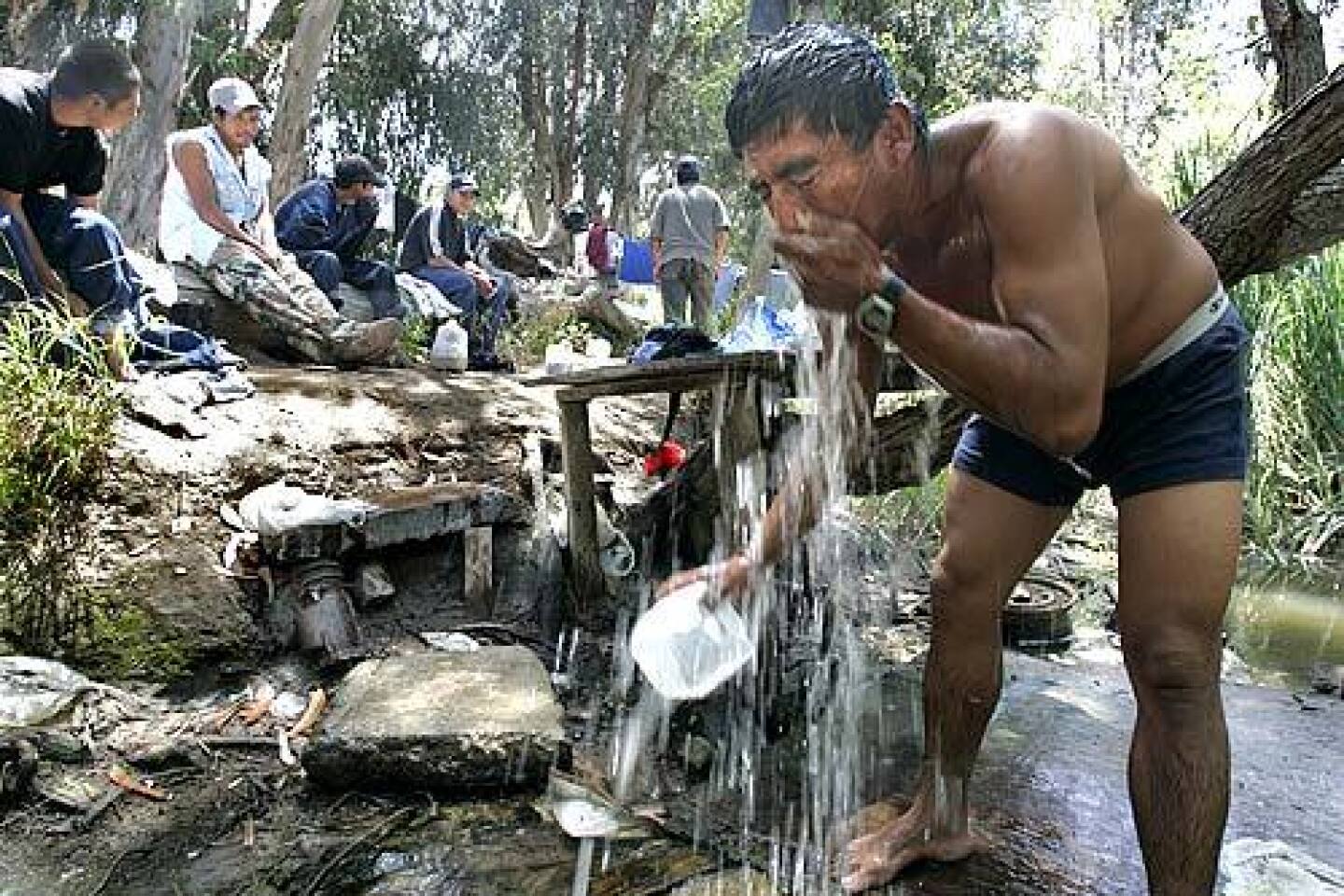

A few hundred miles away, in the canyons of Carlsbad north of San Diego, hundreds of farmworkers burrow into the hills each year, covering their shacks with leaves and branches to stay out of view of multimilliondollar homes. They live without drinking water, toilets, refrigeration. Fireworks and music from nearby Legoland pierce the nighttime skies.

In a larger camp a dozen miles to the south in Del Mar, farmworkers wash their clothes in a stream, bathe in the soapy water, then catch crayfish that they boil for dinner.

Scott Washburn was the last UFW organizer to work in the San Diego County camps; when he left in 1981, so did the food cooperative, armored trucks that cashed checks without charge, and doctors and English teachers who made regular visits.

“Man, it’s sad down there,” lamented UFW President Arturo Rodriguez, who has run the union since his father-in-law, Chavez, died in 1993.

Yet his union has done nothing to help.

In the fields, the only Cesar Chavez many farmworkers have heard of is the famous Mexican boxer. “I think right now it’s one of those nice memories for the older people,” Eliseo Medina, one of the most successful labor organizers in the country, said about the farmworker union he once helped lead. “It’s just not the factor it should be, which is unfortunate. Because farmworkers desperately need a strong union.”

Isai Rios has never heard of the UFW. At 17, Rios came to San Diego with his father from Oaxaca. They moved into the Carlsbad camp last spring to work in the strawberry fields across Cannon Road. Home is a shack made of plastic sheets tied to tomato stakes. The housing alternatives are overcrowded, costly and inconvenient — rented rooms in houses shared by as many as 30 people.

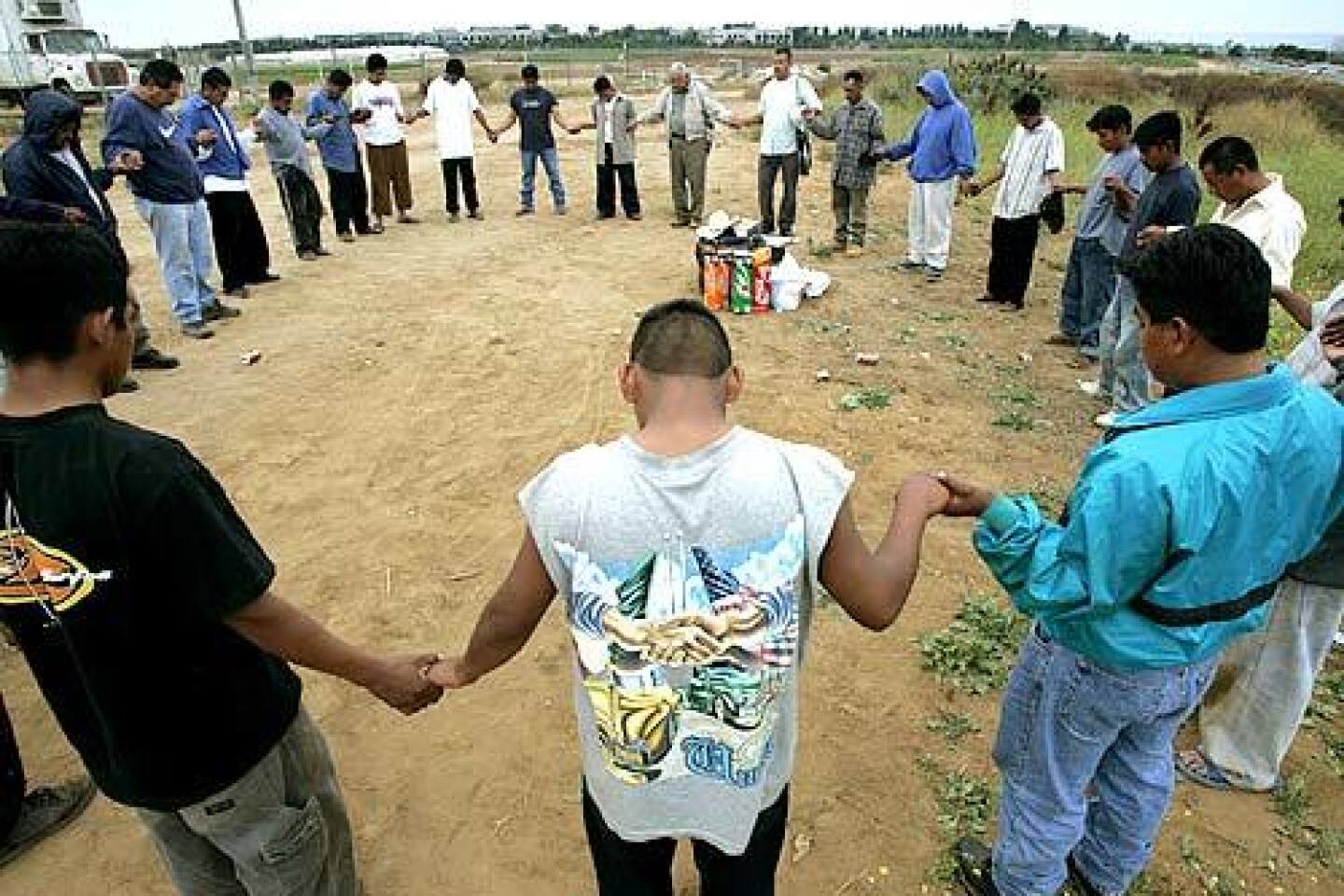

Each Sunday, church volunteers bring jugs of water, garbage bags, ramen noodles and toilet paper to the Carlsbad camp. A clearing just above the road serves as the meeting room, where Rios took Communion at the Wednesday evening Masses, listened to advocates explain basic rights such as overtime and breaks, and tried to learn simple English phrases from college students: “How are you?” and “I feel sick.”

Fernando Bernadino is 33 and has a ninth-grade education, more than most of his co-workers in the Carlsbad camp. His Sunday routine is to pick up free Spanish-language papers while he does laundry in Oceanside, scrubbing hard at strawberry stains that won’t wash out.

He is the kind of worker who in another era might have been recruited to organize for the UFW. He reminds others to clean up garbage so the city will not bother the camps. He cooks most of his meals on a propane stove and packs lunch so he isn’t dependent on the lunch trucks. He seeks out people who can tell him of his rights, and he helps advise others. He is careful to use clean water for drinking and bathing, and examined the vitamin C content of juice drinks before picking mango punch during a recent shopping expedition.

He has a wife and three children at home in Oaxaca, and he is not proud of how he lives here. He has read about Cesar Chavez and considers him a great leader.

“If he were here,” he said, “things would be different.”

A Man and His Cause Capture a Nation’s Attention

On the quintessential American holiday, July 4, 1969, the drawing of a boyish face with a shock of dark hair and faintly Indian features filled the cover of Time magazine: Cesar Chavez and his grape boycott had become a national cause.The short, rather unassuming leader compensated for his flat speaking style with a flair for dramatic gestures: In the midst of a 25-day fast to emphasize nonviolence, Chavez shuffled weakly past television cameras up the escalator of the Kern County Courthouse to comply with a summons. Days later, he broke the fast with Sen. Robert F. Kennedy by his side.

By the summer of 1973, as striking farmworkers filled jails, walked picket lines and faced violent confrontations with Teamsters, Chavez presided over the first convention of the United Farm Workers of America. The preamble to the new constitution spoke eloquently of the need for the union and the determination of its founders:

“We, the Farm Workers of America, have tilled the soil, sown the seed and harvested the crops. We have provided food in abundance for the people in the cities, the nation and the world but have not had sufficient food for our own children . And just as work on the land is arduous, so is the task of building a union. We pledge to struggle as long as it takes to reach our goals.”

In 2002, Chavez’s heirs excised the preamble.

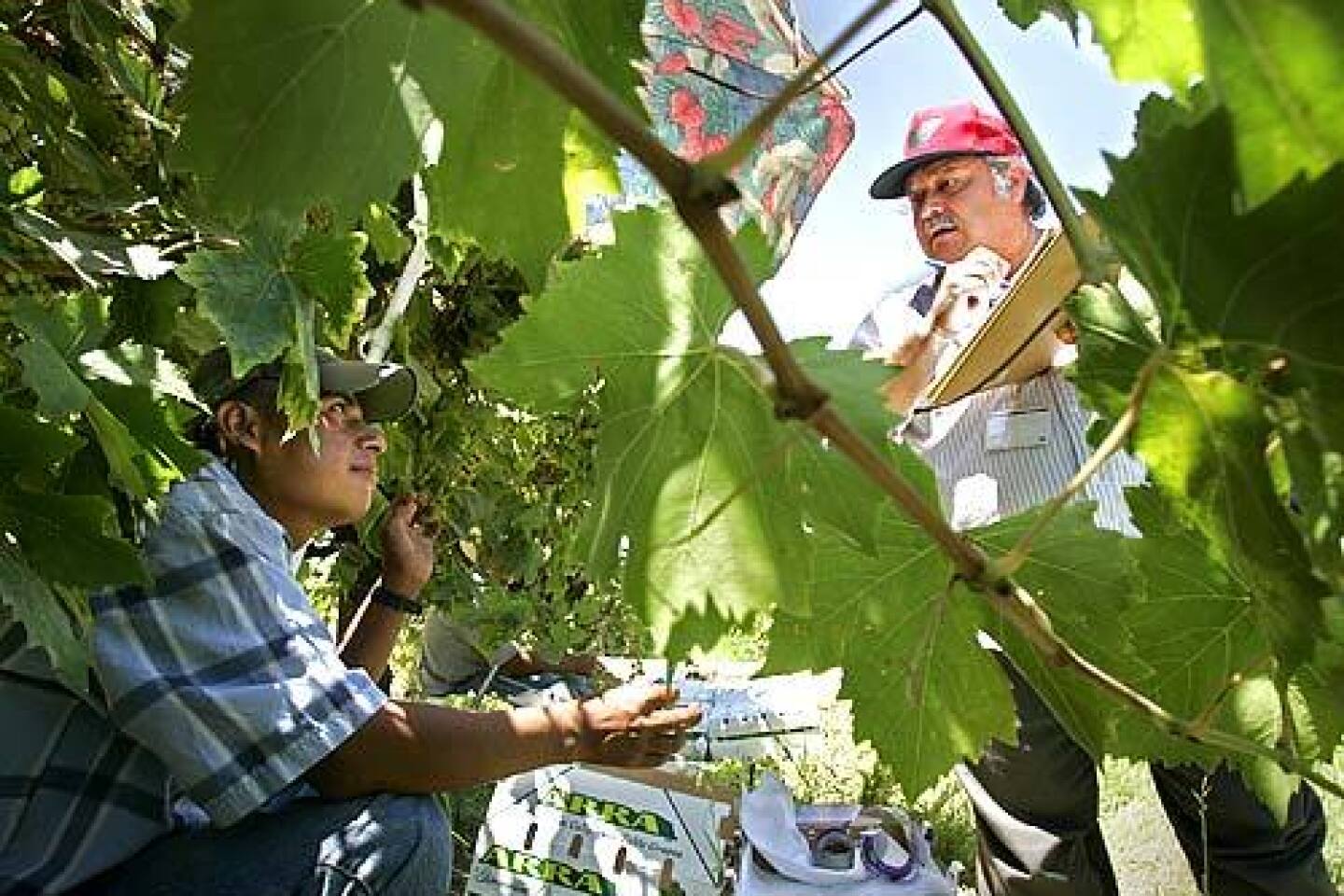

In 2006, the UFW does not have a single contract in the table grape vineyards of the Central Valley where the union was born.

Nor does it have members in many other agricultural swaths of the state: The union Chavez built now represents a tiny fraction of the approximately 450,000 farmworkers laboring in California fields during peak seasons — probably fewer than 7,000.

Precise numbers have always been elusive in an industry dependent on transient, often undocumented workers. The physically grueling, minimum-wage work has historically been the bottom-of-the-rung job for the newest immigrants, today overwhelmingly undocumented Mexicans and, increasingly, indigenous people from the Mexican states of Oaxaca and Guerrero. Employers depend on the undocumented workers, who come north because it is so difficult to make a living back home.

Chavez publicized the oppressive conditions at a time when farmworkers lacked even toilets in the fields. Beginning with the Delano grape strike 40 years ago, the UFW combined picket lines with boycotts, sending farmworkers across the country to talk about their plight. They generated enormous public sympathy, and that translated into economic and political pressures that forced change.

Some gains have been lasting. Older farmworkers talk about learning that even without a union presence they could stand up for their rights. Laws brought farmworkers unemployment benefits, overtime, rest breaks and drinking water.

But the economic gains the UFW achieved have all but evaporated: In real dollars, the $6.75-an-hour minimum wage in California is less than what many farmworkers earned under UFW contracts in the 1980s.

Rodriguez, the UFW president, refused to release a list of contracts or even a number, saying some growers with union employees would face “peer pressure.” He acknowledged there are not many contracts; estimates are between 20 and 30, including several outside California.

As the union lost contracts, the number of workers who qualify for UFW pensions or healthcare plummeted. Fewer than 3,000 farmworkers are covered by the union health plan during peak months, the plan administrator said. The pension plan has more than $100 million in assets, but pays pensions to only 2,411 retirees and has trouble finding more who qualify.

In 2002, assessing the bleak circumstances, the UFW board made a dramatic shift. It changed focus and chose to capitalize on the growing Latino population across the country. The board deleted all specific references in the UFW constitution to agricultural workers, including the preamble.

“Our overall goal is helping to improve the lot of 10 million Latinos by 2015. We’re definitely going to go beyond farmworkers. What those industries are, how we do it, we don’t know yet,” Rodriguez said.

“We’ll never leave our roots. We’ll never abandon farmworkers by any means, or rural communities. But we certainly don’t want to position the organization or the future of the organization to only be dependent on that. There are lots of needs out there that have to be met, and if we have the capacity to be able to do that, then shame on us if we don’t.”

More recently, as he attempts to leverage his union’s position amid a split in the national labor movement, Rodriguez said he saw the UFW’s role as organizing all “food-related” workers.

As part of the Latino strategy, the UFW signed up workers at a Bakersfield furniture store that subsequently went out of business and ran unsuccessful campaigns to represent hotel workers in Texas. UFW members today include Catholic parish workers in Brownsville, Texas, and workers who assemble prefabricated classrooms for a San Jose-based company.

After signing a contract to represent the assemblers, the UFW helped the company petition the state for a job-classification change that would have allowed the firm to pay lower wages on public jobs.

“I support the farmworkers trying to organize and make peoples’ lives better, but when you cross the line and you start undermining other workers’ wages, it’s not acceptable,” said Neil Struthers, head of the Santa Clara County building trades council, which successfully fought off the move. “They have more rights than we do to organize [farmworkers]. They’re not organizing there. They’re organizing whatever falls in their lap.”

Other union leaders question the effectiveness of a pan-Latino approach.

“You’re not going to build a union or a movement that way,” said Medina, a farmworker who became a UFW leader in the 1970s and is now a national executive vice president with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU). “You don’t do it around ethnic lines. You do it around industries. I think what they’re trying to do now is figure out where it’s easier to maintain the institution.”

Focus Is on Raising Money, Not Organizing in the Fields

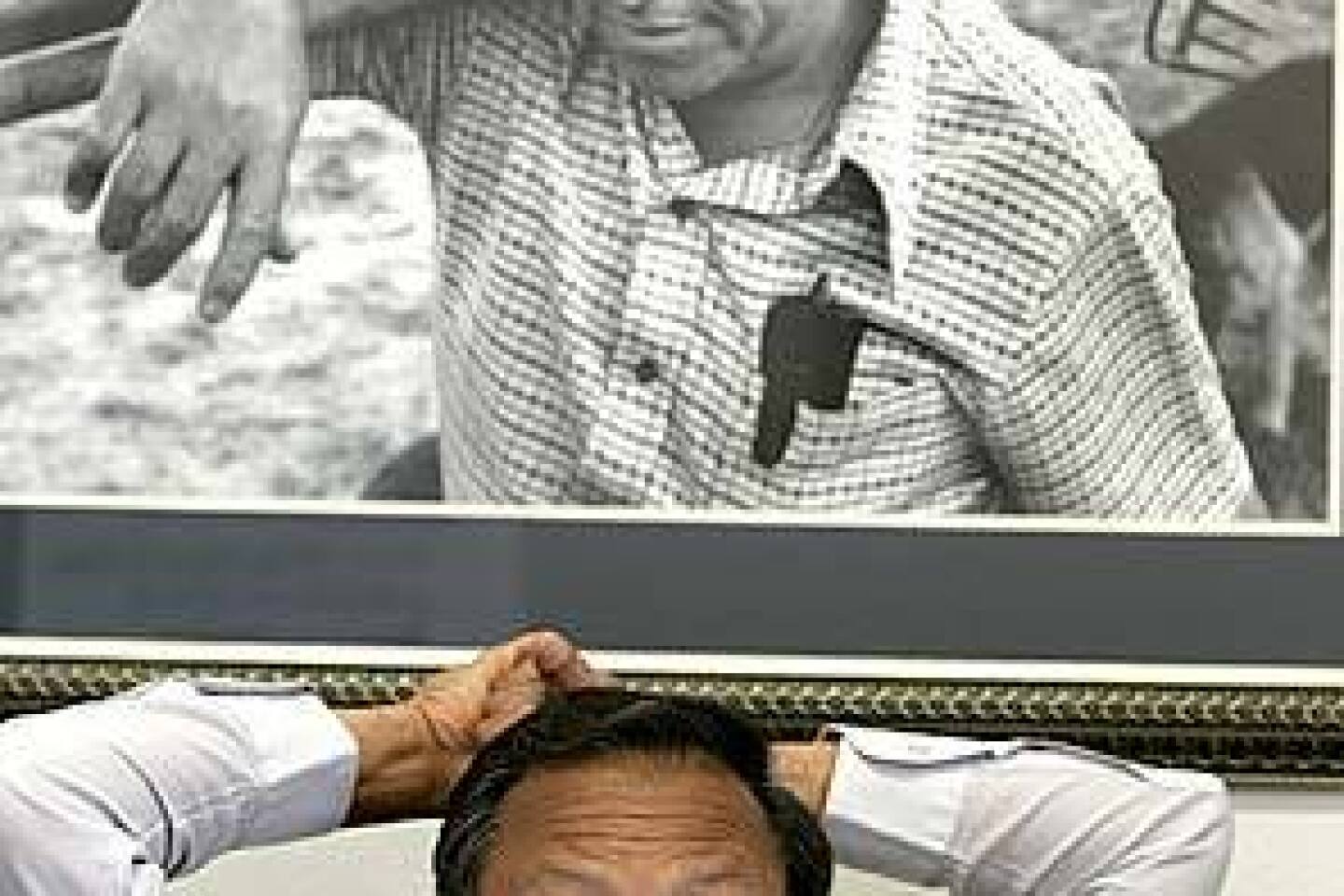

On the wall of the cramped Santa Maria living room that doubles as his office, Pedro Lopez tacked a larger-than-life poster of Cesar Chavez.“Every time I do things, I think of him,” Lopez said.

But the young Oaxacan farmworker has no faith in the UFW.

In the summer of 1999, Lopez helped organize walkouts among Mixtec Indians in the strawberry fields of Santa Maria. He would drive his truck into the fields, climb on top and call workers out in roving strikes. With ripe berries rotting on the vines, startled strawberry growers quickly agreed to increase wages.

Lopez was fired from his job and blacklisted, but the strike only deepened his commitment to organizing. An elementary school graduate who left Mexico at 12, Lopez had only recently learned about Chavez. He called the UFW for help.

The union filed a complaint that successfully recovered back wages for Lopez and others. Then, at a meeting in Santa Maria, Lopez and others recall, UFW Secretary-Treasurer Tanis Ybarra pledged whatever support the workers needed to continue organizing — an office, telephones, a computer.

When Lopez and several leaders of the United Mixtec Farmworkers arrived a few weeks later at the UFW headquarters to work out the details, the story was different.

Anastacio Bautista, then vice president of the Mixtec group, was among those asked to wait outside while the UFW leaders talked to Lopez alone; they offered Lopez a job but said the union had no money to help his group organize in Santa Maria. And they asked for a decision on the spot. Ybarra recalls Lopez wanted a job; Lopez said he wanted organizing support but felt he needed at least a paycheck.

“Pedro abandoned us, but he had no other choice,” Bautista said. “We lost faith. We didn’t want to organize anymore.”

Lopez worked for the UFW for six months but said it was difficult to generate interest in the union because it had not made good on the initial promises.

That did not stop the UFW from using the plight of Lopez’s group to raise money.

“The United Mixtec Farmworkers turned to the United Farm Workers of America for help. Our goal is to restore rights and dignity to the Mixteco Indian farmworkers,” a fundraising e-mail said. “Your gift of $25, $35 or even $50, would help provide legal and organizational support.”

The UFW spent $940,000 last year on direct-mail fundraising appeals, its largest expense after salaries, according to tax returns. Donations account for almost one-third of the UFW’s budget — more than $2 million a year — and consistently total more than member dues, which hover around $2 million.

Lopez never saw the letter about his own organization. Shown the fundraising appeal recently, he shook his head slowly. “That’s not right,” he said. “They didn’t help.

“I believe they had the power to help, but they didn’t want to. Why? I don’t know. They want to do it the easy way. They want to come in when everything’s already done. They don’t want to spend any money.”

California has the only law in the country that protects and regulates union representation for farmworkers, passed in 1975 to end the UFW’s boycotts and strikes. But the law, which mandates quick elections if enough workers petition for them, is seldom used these days.

UFW leaders say the law is not enforced well enough to be effective in combating the power of employers, who have great control over workers’ day-to-day lives.

“You really can’t look a worker in the eye and say, ‘If you stand with us, we have lawyers here who will protect you,’ ” said the UFW’s chief counsel, Marcos Camacho.

Rather than making elections and contracts its primary focus, the UFW has concentrated on selling annual memberships for $40 a year to build grass-roots support. They remind workers that the laminated membership cards can be used for identification, something many undocumented workers lack.

Pedro Lopez is convinced that only contracts will protect the Santa Maria farmworkers. “Fear is the main problem,” Lopez said. “But with a good guide, they’d lose the fear. When they get results, workers aren’t scared.”

In the garage of the small house where Lopez is raising five children, across from acres of vegetable fields, a handful of leaders of the United Mixtec Farmworkers meet each Saturday to strategize. They are not quite sure how to proceed, but they know they’re on their own.

“The UFW says, ‘Organize yourselves first,’ “Lopez said. “People say, ‘If we have to do that anyway, what do we need them for?’ ”

Social Services Funding for Farmworkers Goes Unspent

The goal of the Martin Luther King Farm Workers Fund could not have been clearer: The foundation was “irrevocably dedicated” in 1976 to providing healthcare, education and social services for farmworkers.The UFW leaders were so committed that they made the MLK Fund a standard part of contracts: Employers had to pay a nickel per hour to fund “campesino centers” that would help navigate life outside the fields.

The money has not been spent on farmworkers in more than a decade.

For years, tax returns show the fund has had about $10 million, which sits accumulating interest. Each year, the board doles out a small percentage — the minimum required by law to maintain its tax-exempt status — to support the operations of the Farm Worker Movement.

In 1995, UFW leaders renamed the fund the Cesar E. Chavez Community Development Fund, said Paul Chavez, chairman of the foundation and Cesar’s son.

The fund also lent money to help the National Farm Workers Service Center, a UFW affiliate, rehabilitate an apartment complex — in the hills of San Francisco, nowhere near the fields.

“It’s the money that was paid for our work,” protested Rosario Pelayo, a former UFW leader who picked grapes and vegetables for 20 years and is angry about what happened to payments the union negotiated as a benefit for workers.

When the UFW was focused on organizing farmworkers in the 1960s and 1970s, the union operated its own health clinics and credit union, and offered legal assistance, immigration counseling, social service referrals and income tax preparation.

Today one UFW affiliate, the Farmworker Institute for Leadership and Development, offers two English classes; although farmworkers attend for two hours each evening after work, the classes always have long waiting lists.

Services that were once free are now offered for a price by UFW leaders who use their union credentials to help attract business. Camacho, the chief counsel, recently opened a law office in Glendale that specializes in immigration cases; he advertised for business with a full-page insert in the program at the 40th reunion of the UFW in September.

The UFW-affiliated radio station offers one weekly call-in show on health issues — hosted by a Bakersfield doctor who has paid the station rates as high as $300 an hour for the time.

The tasks of providing legal advice, immigration counsel and healthcare for farmworkers today falls largely to ad hoc coalitions of nonprofit groups and volunteers.

In the fields of northern San Diego County, medical care is a 28-year-old physician assistant in the North County Health Clinic van that comes by the largest camp every few months, with a driver who doubles as record-keeper and fills out the forms for those who can’t write their own names. Blood and urine samples are taken, but it is often hard to find patients to give them the test results.

On a midsummer afternoon, farmworkers straggle back into the dusty Del Mar camp, arriving on foot, by bike, seven in a car. As the mobile van closes up at 5:30, the line out the door is almost as long as the 15 patients the medical staff treated during the two-hour visit.

Built by Nonunion Labor, Homes Not for Farmworkers

Over the last 15 years, the National Farm Workers Service Center has raised $230 million to buy or build more than 3,500 housing units for lower-income families in California, Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.Very few are for farmworkers.

Almost all have been built with nonunion labor.

“It’s a tricky one,” said Paul Chavez, who has run the charity since being tapped as president by his father in 1990. “We do the best we can. You should honor labor; you should help poor people.”

Paul Chavez said that only by paying lower, nonunion wages can he hope to meet the Service Center’s ambitious goal of housing 100,000 people in the next decade. The organization provides housing and services for lower-income families, who work mostly in service, retail and construction jobs.

In many places, Chavez said, it is difficult to find union contractors willing to bid on projects, though the Service Center does solicit bids.

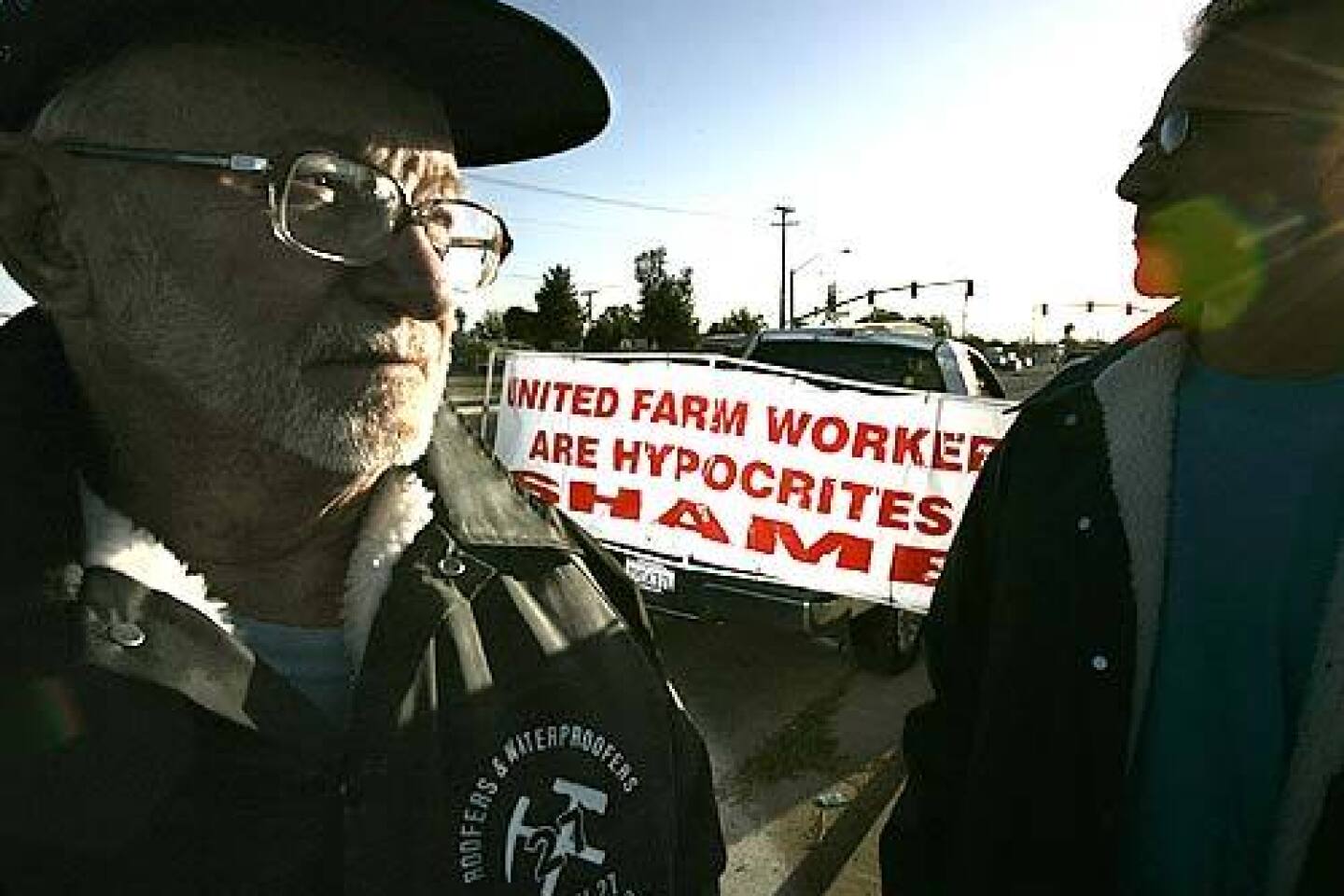

That wasn’t the problem in Bakersfield in November.

When the Service Center rejected a union roofing contractor’s bid as too high, roofers union official Joe Guagliardo denounced it as a double standard, saying farmers use the same rationale to oppose the UFW.

“United Farm Workers Are Hypocrites — Shame,” read the banner Guagliardo draped from his truck, which he parked outside UFW headquarters one weekend. The Service Center reversed itself and told the union its roofer would get the job on the Bakersfield apartment complex. “They didn’t want my truck there,” Guagliardo said. “Bad for business.”

Rodriguez, the UFW president, said he was sympathetic to the Service Center’s dilemma. “To me, we’ve got to serve the needs of poor people. That’s what this organization is about,” he said.

Like the Bakersfield project, most of the Service Center housing projects are not aimed at farmworkers, whose low salaries and intermittent work make them less desirable tenants.

Paul Chavez said he will probably follow a recommendation from a strategic retreat: Change the name of the National Farm Workers Service Center’s housing arm to something without “Farm Workers” because it confuses people. “It’s the same problem as Kentucky Fried Chicken,” he said, referring to the fast-food chain’s concern that its name would be incongruous when it launched a line of nonfried food. “So they call it KFC.”

Seasonal work and low incomes make it difficult to finance farmworker housing projects without major subsidies, said Manuel Bernal, a housing expert Chavez brought in a few years ago to run the department.

“You don’t have any continuous income to finance the mortgage. That’s why we’ve basically stayed out of it,” he said. “Second, even if you had the income, there’s been a concern — more than a concern, a lesson learned — that farmworkers may not necessarily want to spend the money to live under our housing model because they’d rather save to send the money back home.”

Decent, affordable housing is one of the most critical needs for farmworkers across California. The real estate boom has made sheds, garages, overcrowded apartments and shacks even more common accommodations.

A bargain in Salinas is a tiny one-bedroom apartment for a family of four in a 1950s labor camp with a board where the window should be and a hole in the roof. The tenant, who once organized her neighbors to protest poor conditions, is now afraid to complain for fear she would be evicted or the camp shut down; she could not find another place to live for the $450 a month she pays in rent.

In San Diego, a coalition of advocates, lawyers and religious leaders has been trying for years to work out a plan with the city of Carlsbad to build housing for farmworkers who live in shacks in the hills. So far, each proposal has been defeated by community opposition.

In the sprawling Del Mar camp where hundreds of farmworkers live at the height of the season, neighborhoods are defined by Mexican hometowns. The trees provide camouflage, hiding the shacks, while their branches double as closets. Frying pans, toothbrushes and plastic bags stuffed with clothes dangle from limbs.

One afternoon, three friends built a home from scrap lumber scavenged from construction sites; it took 10 minutes to cut one two-by-four because the handle kept coming off the ancient, rusted saw.

Jose Gonzalez, who lived in the camps when he first came from Oaxaca two decades ago, now works as a night manager at Rite Aid and spends his spare time trying to help more recent arrivals. He worries most about drinking water and pesticide contamination. “In jail we have criminals who have better living conditions,” he said. “Why can’t we do that with the hardworking people?”

Banking on the UFW Brand to Build Political Clout

In 1998, political consultant Richard Ross showed UFW leaders a statewide poll of Latino voters. The UFW ranked at the top as a name to trust.“Richie just said, ‘This is gold,’ ” UFW Political Director Giev Kashkooli recalled.

From then on, the union has been selling its brand.

In 1999, the union began running political campaigns as a business. Since 2000, the union and several related nonprofits have received close to $1 million from state campaign committees alone, a combination of civic donations and payments for election help.

Most unions contribute money to candidates; the UFW collects it instead. Most unions give money to their political action committees; the United Farm Workers PAC pays the union.

“We’re unusual in that we actually get paid to run campaigns,” Kashkooli said.

The UFW frequently works on campaigns in areas where it does not have members but ranks high in polls, such as Long Beach, and where candidates believe the affiliation will help their cause. They are often campaigns advised by Ross, a lobbyist who also works for the UFW.

In Calexico last spring, for example, the Viejas Indians paid the UFW $75,000 to run a campaign to win approval for a casino in the Imperial Valley city. Rodriguez sent letters urging support and enclosing a UFW pin with an eagle.

“I have a very soft spot for the union; it was kind of a blow to see that we were on opposite sides of the fence,” said Mary Rangel-Ortega, an Imperial County educator who led the losing fight against the measure.

Politicians at all levels of office routinely contribute to the annual Chavez Foundation fundraising dinners, turn out for the walkathons and buy ads in the programs for the UFW conventions. Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa is featured prominently on the UFW website advertising “Sí se puede” wristbands.

Political clout has also helped the farmworker movement obtain public funds — more than $10 million in state money alone in recent years, not counting low-interest housing loans and tax credits.

“The union was able to help us build the political support for the funding,” said Andres Irlando, who recently stepped down as president of the Chavez Foundation, which has been awarded more than $5 million in state grants to build a visitor center, memorial garden and retreat center around the UFW headquarters where Chavez lived and worked.

In 2002, the union used its political strength to achieve a major legislative victory, a law that imposes mandatory mediation if contract negotiations reach an impasse at a farm where the union has won an election to represent the workers. The UFW reported spending $241,432 on lobbying that year, money that paid for lobbyists and mass demonstrations to pressure then-Gov. Gray Davis to sign the bill — a 10-day march and chartered buses to bring supporters to the Capitol.

The UFW has invoked the law only once, although there are dozens of companies to which it could apply. Union officials said they are waiting to see if it withstands a court challenge.

Rodriguez, the union president, said politics has become an important part of the UFW’s work. “We take the positive things that we’ve been blessed with — Cesar’s image and the name and the reputation and the symbol of the black eagle — and we utilize that to empower Latinos,” Rodriguez said. “We’ve not necessarily branded it that way, but others have branded this as a symbol for Latino empowerment.”

That effort helps the entire labor movement, said John Wilhelm, president of the hospitality division of the labor union Unite Here: “I think that the moral authority of the farmworkers has never been questioned and I think that’s of tremendous value at a time when the labor movement is not well regarded by lots of people in society.”

Rodriguez moves comfortably in the world of politics and power and was proud of his role in negotiating regulations to mitigate extreme heat stress last summer. The new rules were announced at a joint news conference with Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, after several farmworkers collapsed and died during unusually hot weather.

The heat-related deaths gave the UFW an organizing opportunity as well as a political one. Workers at Giumarra Vineyards, angered by the deaths and poor working conditions, had come to the union asking for help. The UFW attempted late last summer to win an election to represent the workers, in the heart of table grape country.

The night before the Sept. 1 vote, the union president was in Sacramento, hosting a fundraiser for the UFW Foundation. Formerly named the Farm Workers Health Group when it helped fund health services, the nonprofit organization now has no clear mission. Rodriguez, president of the board, said it might focus on immigration issues.

The invitations for the September fundraiser said contributions would go to a nonpartisan fund to help register farmworkers to vote, but Rodriguez described the purpose differently. He thanked the donors for their support and talked about using the money to fight for immigration reform. He mentioned the Giumarra vote and talked confidently about prevailing as he mingled with supporters. “Pray for us tonight because we have a big election tomorrow,” he said.

The next day, in Sacramento, a gay-marriage bill passed the Senate. Sponsors attributed key votes to public support from the UFW and the union’s aggressive lobbying of Latino lawmakers. While the legislators were approving gay marriage, farmworkers at the country’s largest table grape company were rejecting the UFW.

*

About This Series

Today: The UFW betrays its legacy as farmworkers struggle.

Monday: The family business: Insiders benefit amid a complex web of charities.

Tuesday: The roots of today’s problems go back three decades.

Wednesday: A UFW success story — but not in the fields.

On the Web

For additional photos, visit latimes.com/ufw.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

UFW budget

The UFW is an unusual union for its reliance on donations, which have grown in importance as the number of its labor contracts has declined. Dues, 2% of workers’ wages, once made up as much as two-thirds of the total revenue.

Total revenues

1971: $1.85 million

Initial wave of contracts that followed grape boycott.

Dues 60%

Donations 24%

Other 16%

1978: $2.43 million

UFW grew after the 1975 Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which allowed farmworker union elections.

Dues 61%

Donations 20%

Other 19%

1982: $4.53 million

Peak in dues reflects wage increases after a 1979 vegetable strike.

Dues 66%

Donations 6%

Other 28%

2004*: $6.64 million

Dues have declined, reflecting about 20 to 30 contracts. UFW officials won’t say how many.

Dues 31%

Donations 35%

Other 34%

-

2004 budget breakdown

Expenses total: $7,216,385

| Officers’ compensation | $548,094 |

| Other payroll | 2,406,984 |

| Professional fees (legal, | |

| accounting, consulting) | 1,027,481 |

| Direct mail (fundraising) | 819,249 |

| Travel/vehicle | 395,275 |

| Rent | 310,961 |

| Telephone | 225,805 |

| Affiliation with AFL-CIO | 163,996 |

| Conferences | 144,372 |

| Postage | 96,370 |

| Other | 1,077,798 |

-

Revenues total: $6,638,239

| Donations | $2,295,943 | |

| Dues | 2,074,575 | |

| AFL-CIO organizing support | 693,000 | |

| Services** | 535,766 | |

| Fees*** | 444,446 | |

| Sale of supplies | 210,368 | |

| Sale of real estate | 197,000 | |

| Events | 92,034 | |

| Supporting memberships | 47,376 | |

| Other | 47,731 |

Net assets: $1,523,066

-

* Most recent data available

** Payments from other nonprofits in the movement for services such as accounting, human resources and technical support.

*** Includes payments for running political campaigns and for member services provided to the pension and health funds.

-

Source: Annual Form LM2 reports to the U.S. Department of Labor. Graphics reporting by Miriam Pawel

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.