For skid row residents and advocates, mural is a sign of survival

Skid row is the place that dares not speak its name.

The neighborhood of 10,000 people on the eastern end of downtown Los Angeles — with the largest concentration of homeless people in the country — is generally not listed on municipal signs or maps. The local firehouse was ordered years ago to take “skid row” off its ambulances and rigs.

As bars, lofts and restaurants started to pop up in skid row’s traditional territory, the city — prodded by business groups — began using names like Old Bank District, Historic Core, Central City East or Industrial District to describe parts of the 50-block area.

This month, a group of residents sought to reclaim their turf, at least symbolically. They put the final touches on an 18-by-50-foot mural with a detailed street map of the area and a clear message: Skid row is a legitimate Los Angeles neighborhood, and should not be erased.

Organizers call “Skid Row Super Mural” a show of pride and self-determination by a community sick of being defined by its most unfortunate citizens. Detractors say the mural is a misguided attempt to paper over the misery of the homeless enclave.

City Councilman Jose Huizar says it is the kind of art he envisioned when he pushed in October to lift the city’s 11-year-old mural ban.

“It’s community pride on the one hand, it’s cleverly done and it creates conversation and debate, which often great public art does,” said Huizar spokesman Rick Coca.

The San Julian Street project, which was registered under the city’s mural ordinance, is on the wall of a property known as Bob’s Bakery owned by businessman Peter Ta, according to city records.

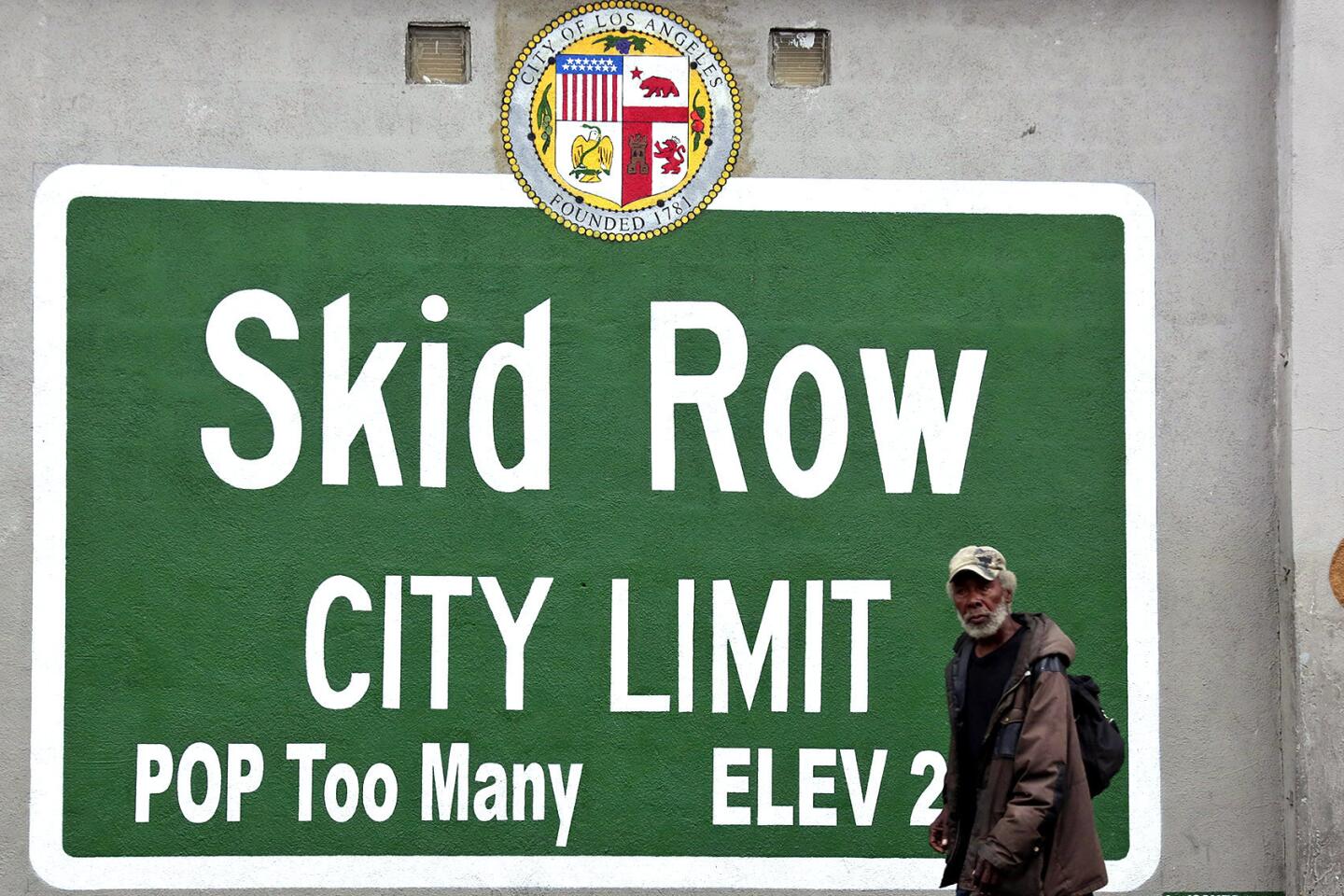

The first phase, which went up in February, depicts the city seal and the words “Skid Row City Limit” in the familiar white-on-green lettering of official signage. In a jab at the city’s failure on the homelessness front, the population is listed as “Too Many.”

In another quietly subversive touch, the map text states that its boundaries are taken from Jones vs. City of Los Angeles, a court case that barred nighttime homeless sweeps by police. It was unveiled Aug. 1.

“The mural is the history of the community,” said Isabel Rojas-Williams, executive director of the Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles. “It’s very cleverly done.”

General Jeff Page, a formerly homeless activist who created the project, said he is as appalled as anyone that people languish in the streets. But skid row is not just people lying on sidewalks getting high, he said.

While City Hall was sleeping, he added, thousands of skid row residents — whose rehabbed flophouses and apartment projects are protected by covenants for a generation — have been bettering the community.

“A lot of success going on skid row is overlooked,” Page said, adding that business owners “think it’s going to be so cool, so brave to open a business here, but they don’t say it was skid row that led the way.”

The mural was designed by Stephen Zeigler and painted by street artists calling themselves the Winston Death Squad, among them a man known as Wild Life, whose work often spoofs official signs.

“I was impressed by the variety of race and income brackets. It was dirty and gritty,” said Zeigler, a commercial photographer who opened a skid row art gallery after moving from Manhattan Beach. “Some of the people I call friends live in tents. “

The optimistic picture of the skid row community is not shared by everyone.

Raquel Beard, who heads the Central City East Assn., the local business group, said the skid row she sees everyday is a place of pain, misery and degradation.

“Maybe in 10 years it will be an urban and edgy,” she said, “but before I can jump to skid row chic we have bigger issues to deal with. Let’s heal, then they can think about it as jazzy.”

Izek Shomof, a pioneering downtown loft developer, said he sees nothing to celebrate in the name skid row.

Shomof, whose partnership bought three aging skid row hotels in 2013 to make over for struggling artists, actors and musicians, said some people who claim skid row as their turf are in favor of letting homeless people live in the streets.

“Whatever they name it, something needs to be done,” said Shomof, who describes his properties as “just outside” skid row, although they are well within the mural’s boundaries. “It’s absolutely inhumane to have somebody lying on the street.”

Page, however, foresees a day when the skid row mural will join the Hollywood and Rodeo Drive signs as L.A. icons.

That day may be far off. Directly across from the mural, men and a few women were splayed out on the sidewalk, smoking a street drug called spice, or chanting in languages known only to themselves.

Passers-by seemed more baffled than bowled over by the artwork.

“It’s like a prison, with walls where the cops keep them in certain areas,” said Richard Kelly, a law clerk, pointing to the map’s street grid.

Said a homeless man who calls himself White Boy: “I love the General and I wish him well, but society’s not ready for skid row. It’s a 20-year plan for skid row and when it ends no way we’re in it.”

Residents, however, are lining up for proud photos with the mural, the artists said.

During the painting, Zeigler said, a homeless man approached him and suggested the artists add a compass rose, the map feature designating north, south, east and west.

The man, it turned out, had been a cartographer. He gave Zeigler a $5 bill to go toward the estimated $1,000 in mural expenses, most of which were picked up by Page, Zeigler said.

“This guy lives in a tent and he’s giving me money to help with the mural,” Zeigler said. “This is a real community.”

Twitter: @geholland

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.