Bill targets new construction in California quake zones

A state lawmaker is introducing a bill that would close a loophole that has allowed developers to build projects on or near dangerous earthquake faults.

California law already bans the construction of new buildings on top of faults that have been zoned by the state. But more than two dozen major faults have not been zoned, and a Times review found some buildings had been constructed along them.

Statewide, about 2,000 of California’s 7,000 miles of faults have not been zoned, and the building ban is not enforced in those areas.

State Sen. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance) said developers should be required to search for earthquake faults along those remaining areas.

“This is to prevent future buildings from being built on fault lines,” Lieu said in an interview. “Developers right now can ignore that there’s a fault line, simply because it hasn’t been technically zoned yet.”

Lieu cited the results of a Times investigation in December, which found that Los Angeles and Santa Monica in the last decade approved more than a dozen construction projects on or near two well-known faults without requiring seismic studies to determine whether the buildings could be destroyed in an earthquake.

If state officials had drawn a zone around those two earthquake faults, the developers would have been required to dig to see whether a fault was underneath the project before approving construction.

The loophole has led to situations where buildings might be constructed on earthquake faults, putting them at risk for severe damage during an earthquake.

Questions have been raised about whether a fault exists under Blvd6200, a $200-million residential and commercial development under construction in Hollywood. The developer’s geologist was not required to do an in-depth fault investigation by the city. Based on his observations during excavation, he said there was no fault underneath the site. State geology officials later said they were confident a fault exists there.

“The intent is to prevent other projects too close to faults from going forward when there are still 2,000 miles” of unzoned faults, Lieu said. “This bill technically closes that loophole and treats that fault line like it’s a zoned fault line.”

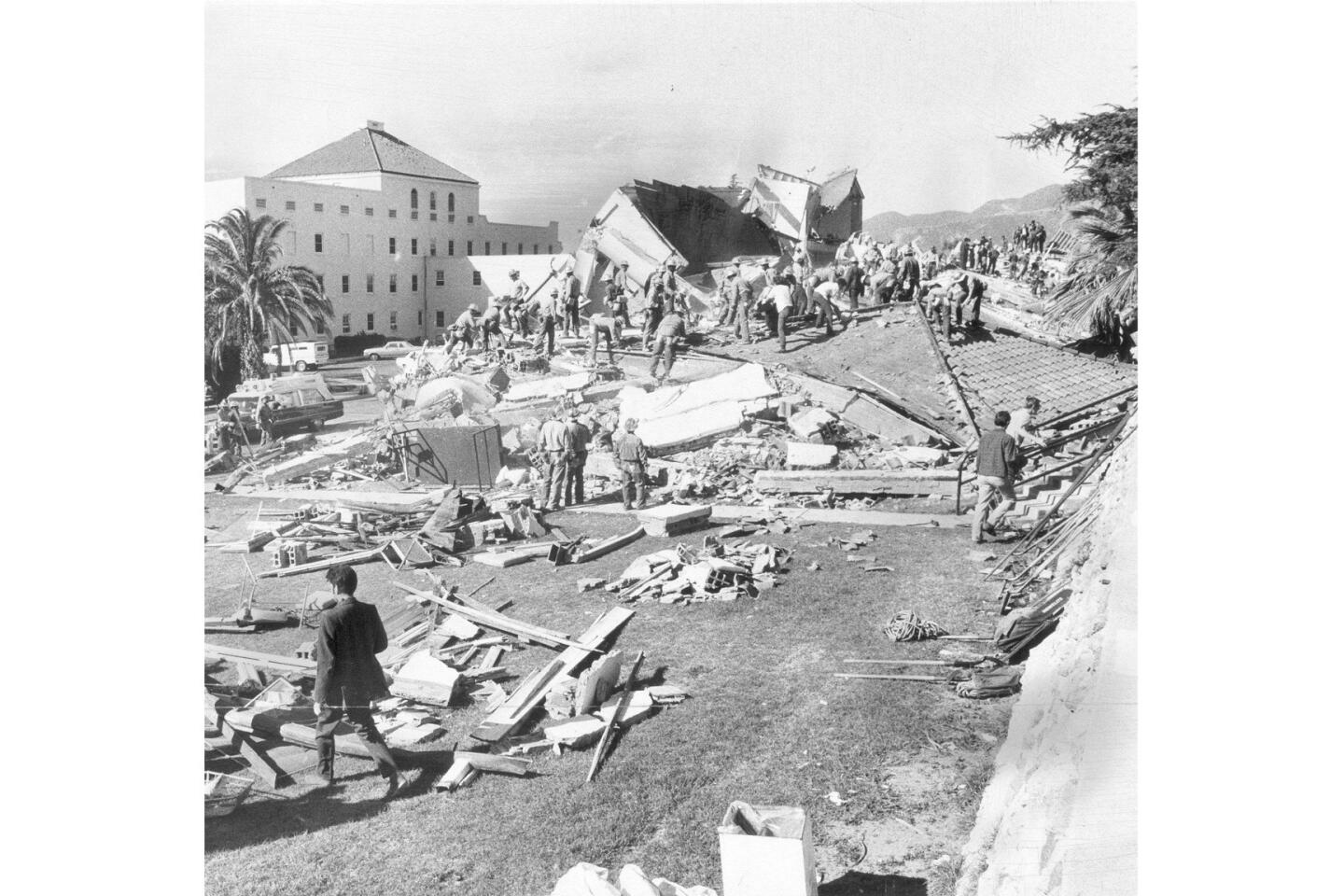

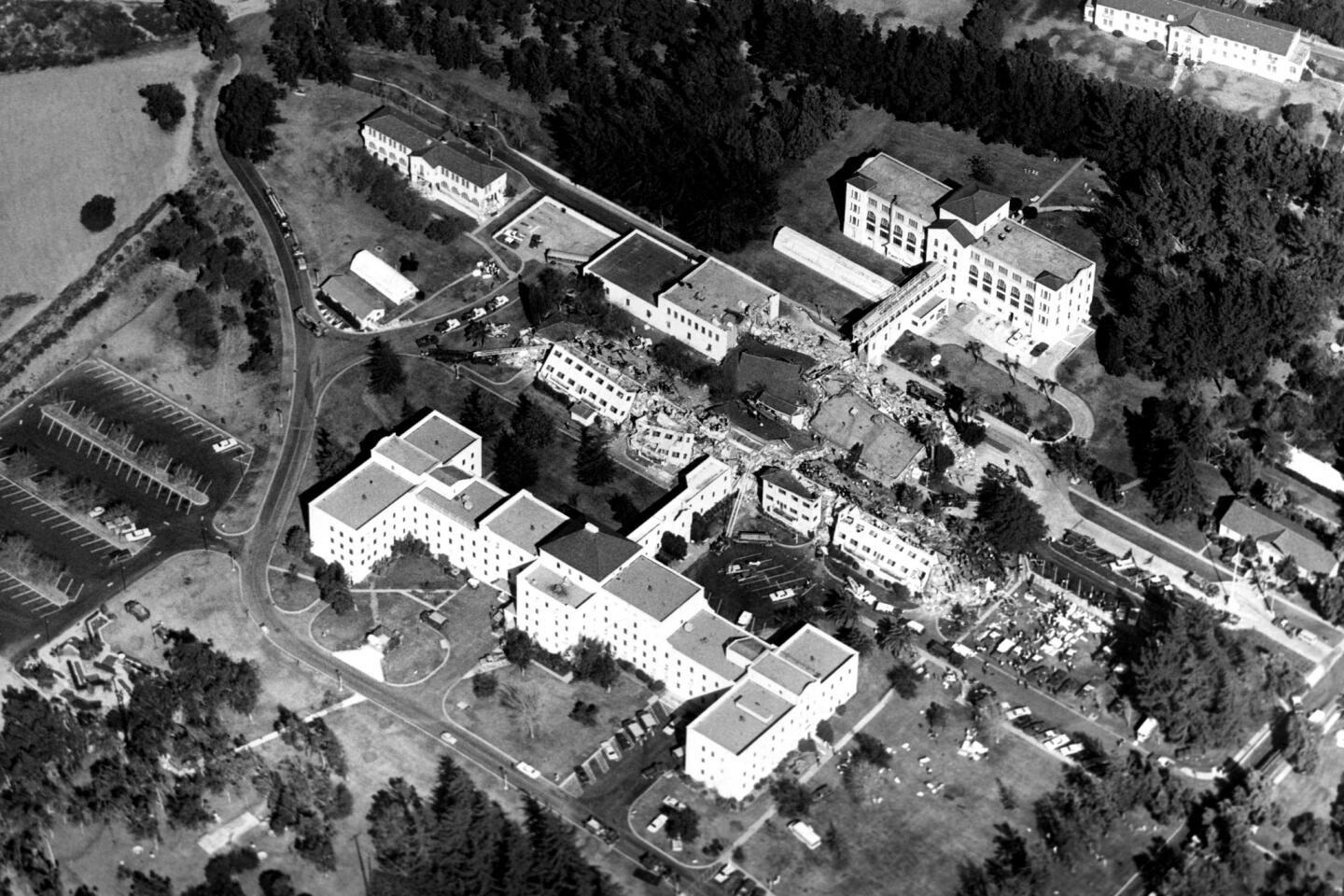

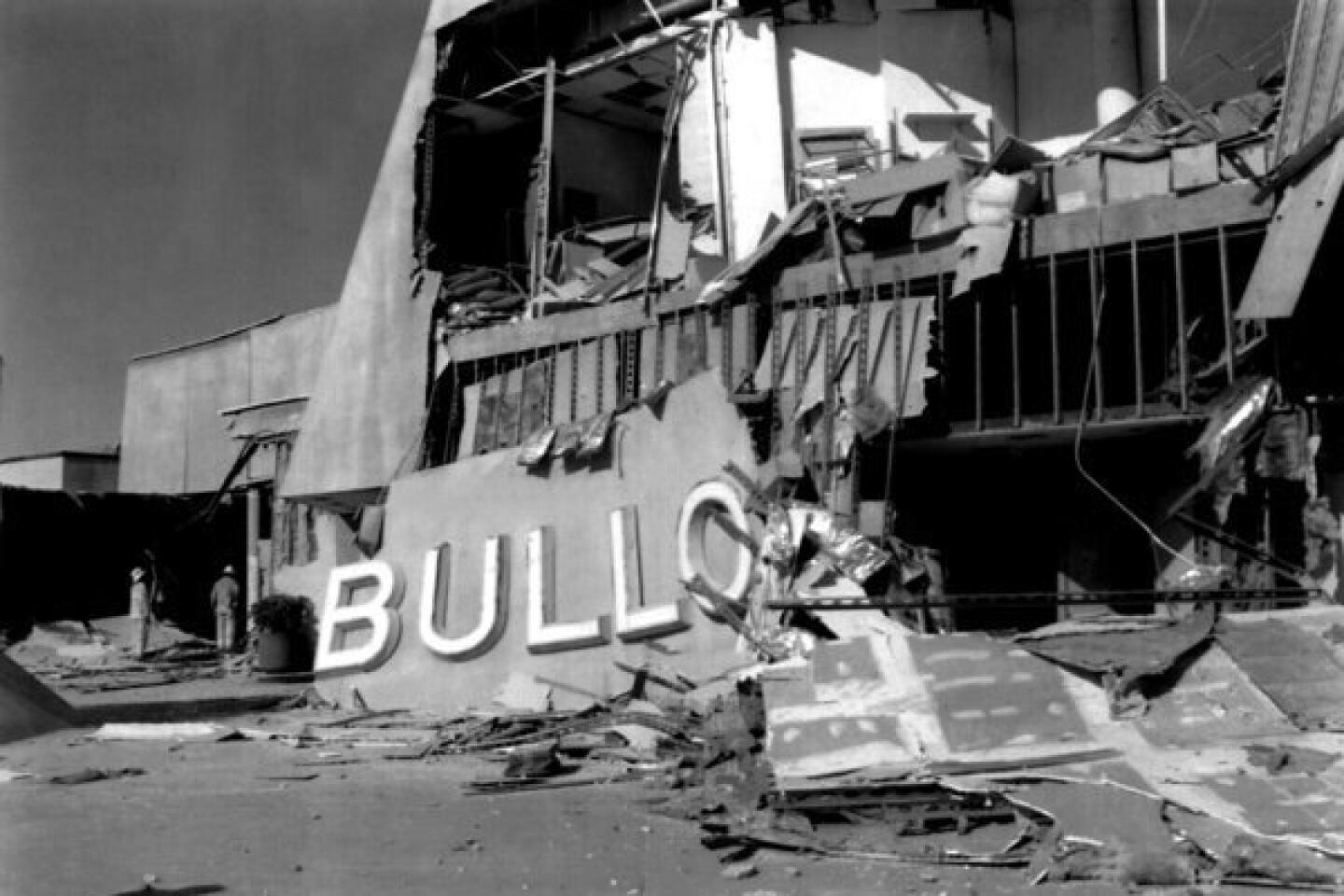

Lawmakers banned the construction of new buildings on top of active surface faults after the 1971 Sylmar earthquake, when buildings straddling the San Fernando fault were ripped apart. One side of the fault shifted from the other by as much as 8 feet. About 80% of the buildings along the fault suffered moderate to severe damage.

Other agencies have gone out of their way to avoid faults. The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority has spent millions to ensure subway stations aren’t built on fissures. Some school districts have decided to tear down classrooms that straddle faults.

Mott Smith, a board member of a statewide developers group, the Council of Infill Builders, questioned whether it made sense to focus on new buildings before tackling older structures built before modern quake codes.

“We should be focusing on older buildings. Instead, we’re focusing on development, and that just isn’t where the biggest problem is,” Smith said.

Smith said he was also concerned that Lieu’s proposal shortcuts the state’s normal process for zoning faults, which can take months of scientific research.

More digging of trenches to find faults would increase costs, another barrier to development, he said.

Bruce Clark, a retired engineering geologist and former chairman of the California Seismic Safety Commission, wondered whether the proposal could cast too wide a net and end up with some developers spending money only to find out their land isn’t on top of a fault.

Still, “compared to a few hundred million for a project, it’s small change. It’s not a tremendously expensive thing,” Clark said. “It is not a good idea to build a building across a fault.… When you have a fault rip a building apart, you really put the people inside at risk.”

The state’s top geologist has previously told The Times it is a good idea to do fault investigations before construction begins.

“Why would one risk constructing multimillion-dollar investments on ground that is known to be of very high hazard, and place in jeopardy the lives of those who inhabit the building?” said John Parrish, the state geologist. All the land encompassed by the state’s existing earthquake fault zones totals about 0.86% of California.

“Reducing the loss of human lives, property, and to the costs to the economy are what the [law] is designed for,” Parrish said.

Lieu said the California Geological Survey’s existing map of all 7,000 miles of faults, published in 2010, is a good start to determine whether properties need fault investigations.

As a result, to ensure buildings aren’t constructed on faults not yet drawn into a quake zone, Lieu said he was proposing any projects within about 500 feet of the fault line undergo a seismic evaluation.

Lieu’s legislation would have a similar effect as a new Los Angeles building policy. A city spokesman in November said Los Angeles would use the state’s 2010 map to determine whether a fault study should be done before construction begins.

Over the last two decades, zoning these faults have slowed to a crawl because of budget cuts. Gov. Jerry Brown last month proposed a sharp increase in funding to complete the zoning mandated by the 1972 Alquist-Priolo Earthquake Fault Zoning Act.

Lieu said his legislation would close the loophole until the state geologist completed the fault zones.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.