LAUSD launches its drive to equip every student with iPads

Two local elementary schools became the first to roll out tablet computers Tuesday in a $1-billion effort to put iPads in the hands of every student in the Los Angeles Unified School District.

For Broadacres, in Carson, the tablets were an exhilarating upgrade for a campus that had no wireless Internet and few working computers. Technology was only marginally better at Cimarron, in Hawthorne, where the computer lab couldn’t accommodate an entire class.

“This is going to level the playing field as far as what schools are doing throughout the district,” said Principal Cynthia M. Williams of Cimarron, where 70% of students are from low-income families.

L.A. schools Supt. John Deasy has pushed for the technology, which will cost about $1 billion — half of that for the Apple tablets and about half for other expenses, such as installing a wireless network on every campus. The vast majority of the cost will be covered by school construction bonds, a payment method that has sparked some concerns and legal and logistical hurdles.

Not everyone is sold on whether the tablets will improve learning.

Still, the hope is that the effort will improve teaching and boost achievement — as well as put a school district composed mostly of low-income, minority students on an even footing with more prosperous students, who have such devices at home, at school or both.

“It gives us the sense of hope that these kids are being looked after, that they’re now able to move into the future,” said Dwayne Loughridge, a parent who also works as a Broadacres campus aide. “It gives them a sense of aspiration and inspiration ... that we’re not left out.”

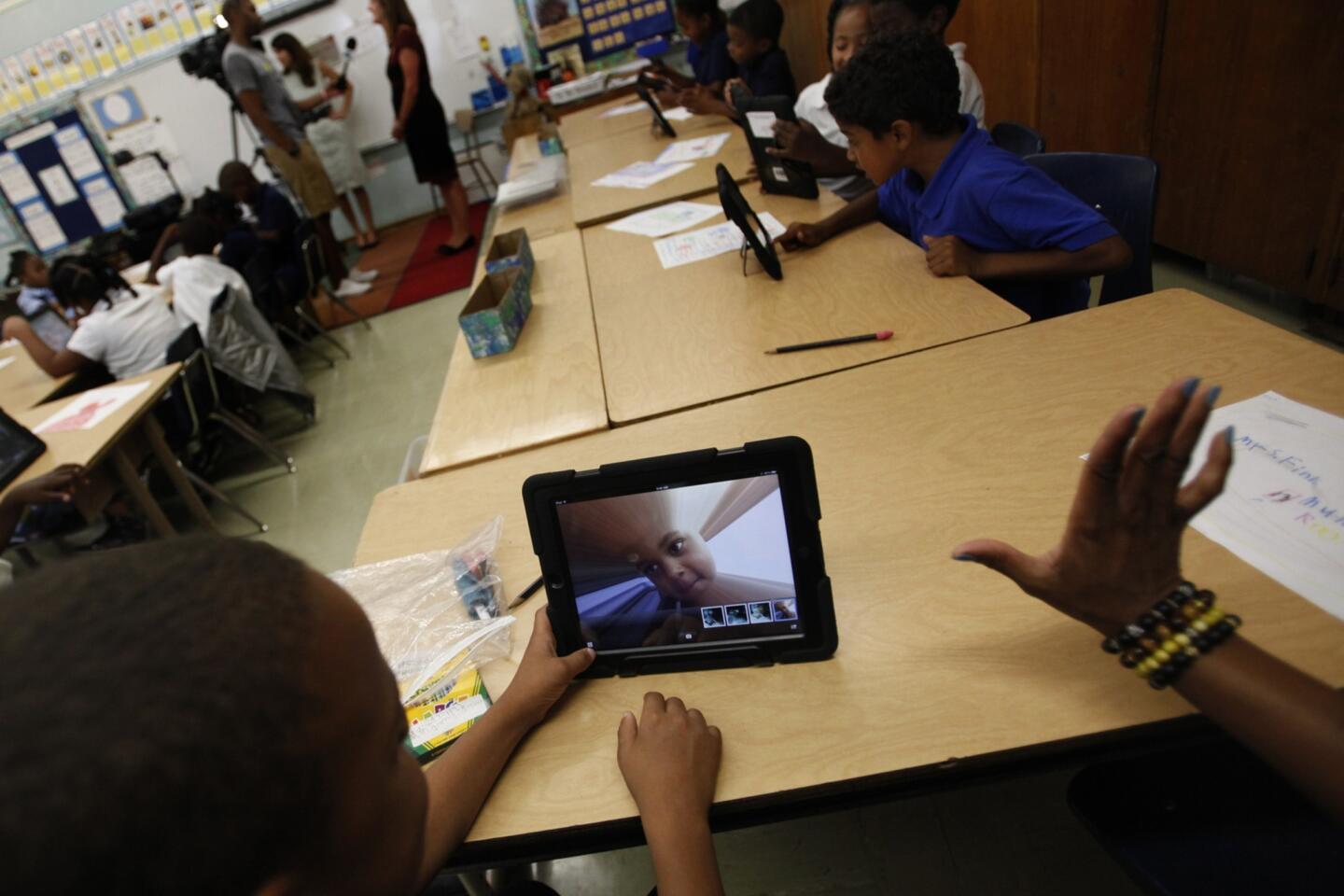

To students in Karen Finkel’s second-grade class, the tablets initially seemed like toys.

“I’m having fun on this iPad,” said Beautiful Morris, who was using a photo-effects app to distort an image of her face in the manner of a fun-house mirror. She also tried out a kaleidoscope effect and a double mirror.

Her teacher’s typically orderly class was distinctly turbulent in the morning as students explored their iPads amid a swirl of district staff and visitors.

By the afternoon, at Cimarron, third-grade teacher Tiffany DeCoursey was trying out a lesson inspired by the children’s book “Have You Filled a Bucket Today?”

Students drew a bucket on their iPads with a finger, then typed in what they wanted it to contain.

It’s the kind of activity that could be done with paper, pencil and crayons, but DeCoursey is excited by the potential of the device. “At the beginning of the year you usually have arts and crafts projects,” DeCoursey said. “Now they can create movies. If they have a burning question and I don’t have an answer, now they can Google. It’s literally going to bring the world into the classroom, but positively.”

DeCoursey had three days of training on both the iPad and the state’s new learning standards, which she’s supposed to teach with the devices.

That pace concerns Brandon Martinez, a professor at USC’s Rossier School of Education.

“Having an iPad for personal use is not the same as using it to instruct students,” Martinez said. “Before you put any kind of technology into the hands of students, the teachers have to be fully trained and capable of using it to teach.”

Over the next two weeks, iPads will be distributed at 45 other campuses. The district’s 650,000 students, from kindergarten on up, are supposed to receive them over the next year or so.

The district is paying $678 per device — higher than tablets cost in stores — with pre-loaded educational software that has been only partially developed. The tablets come with tracking software, a sturdy case and a three-year warranty.

The district is using school construction bonds, approved by Los Angeles voters, which didn’t mention the purchase of iPads. This factor raised questions among members of the appointed Bond Oversight Committee.

School bonds typically pay for construction. The permanent installation of a wireless network, for example, would certainly qualify. And computers installed in a lab conform to spending rules, in the view of many, since they aren’t removed from school grounds.

Tablets, however, are potentially a different matter because students will be taking them home. This raised a legal issue about spending bond money to pay for them.

For that reason, district officials told the committee in January that the tablets wouldn’t leave the schools during this first test phase. After the oversight committee narrowly endorsed the project, district officials changed their minds.

Another issue was whether it’s legal to buy tablets, with an estimated life of three to five years, with bonds that taxpayers would retire over 25 years. Early on, the district talked of using short-term bonds that would match the life of the tablets.

But officials have since decided that regular, long-term bonds can be legally used, provided that some of the money goes to projects, such as buildings, with a longer lifespan, said John Walsh, L.A. Unified’s director of finance policy.

Even so, the devices also will consume a significant portion of money that could otherwise repair and maintain campuses, said Stuart Magruder, an architect who sits on the committee.

“I don’t think we should be using bond funds for this purchase,” he said.

For students and parents Tuesday, the focus was on the thrill of receiving cutting-edge technology. Parents had to sign a form taking responsibility for the devices, which Brenda Brandon was delighted to do just before school as her daughter, Krystal, 7, waited impatiently.

Said her father, Edward Brandon: “There was nothing like this when I was in school.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.