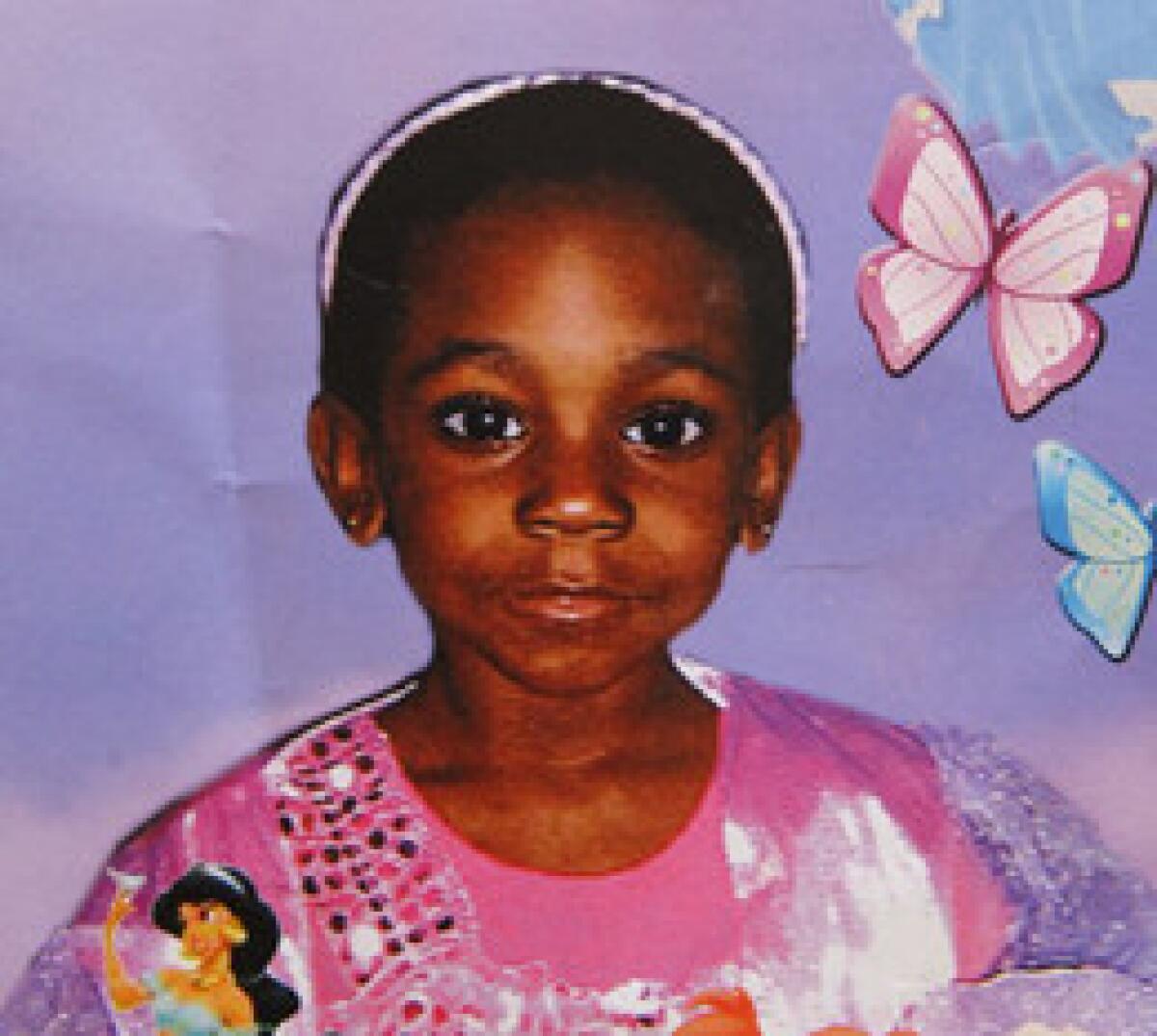

Jada’s case highlights problems in foster care system

Sheriff’s deputies discovered 4-year-old Jada in a painful crouch, unable to sit or stand.

Doctors had to sedate her to peel off her clothes, revealing that 65% of her body was covered with second- and third-degree burns.

Her foster mother held her under scalding water as punishment, ordering another child to help submerge her, according to a criminal child abuse case filed against the woman.

Today, Jada is 14, but the physical and mental scars have never healed. Her case shows a system that is willing to tolerate a criminal record, mental illness and past abuse complaints to fill desperately needed spots for foster parents.

“Doesn’t take long to see that all that hurt is still there,” said Esther, who later adopted Jada and asked that her last name not be published to protect the girl’s identity.

There were early signs of trouble in Jada’s foster home. Two callers previously reported to the county child abuse hotline that foster mother Audrey Chatmon had battered and badly scalded another toddler at her apartment in Lakewood.

Chatmon had been convicted in the 1970s for forgery and another time in the 1980s for using a child to commit welfare fraud. The state granted her a waiver to become a foster parent.

For two decades, private foster agencies approved Chatmon, a high school dropout who had been placed in a mental hospital three times.

Penny Lane was the most recent foster family agency to certify Chatmon. Officials with the agency declined to answer questions about the case.

Three foster children lived in the home. Faith came as an infant, followed by her older sister, Jada, who was 2 when she arrived. They were joined by Monica, 15.

Details of their lives emerged in three court cases — the criminal child abuse case involving Jada and civil cases filed by Jada, Faith and Monica that ended with cash settlements paid by the county.

The children noticed that Chatmon was often drunk and spent her days buried under her covers. She was surrounded by bottles of drugs to treat her bipolar disorder and was under the care of a county psychologist, according to court records.

Monica told the court that she was allowed only a Spartan existence, confined inside the home for long stretches while she cooked, cleaned and cared for the younger ones.

The girls slept on a bare floor without blankets.

Instead of removing the sisters, the Department of Children and Family Services pushed Chatmon to adopt them.

Chatmon disciplined the children by forcing them into scalding water, witnesses testified in court. Jada, missing a tooth and clutching a stuffed animal, testified at Chatmon’s trial. “I was screaming” when “she was holding me down” in the tub, she said.

Asked during the trial if she remembered ever seeing the county social workers assigned to look after her, Jada said “no.”

Chatmon was convicted in 2006 of abusing Jada and is serving a 15-year sentence in the state prison for women in Chino.

After the injury, county social workers placed the girls in a new foster home. They were abused there as well, and had to be removed, according to court records.

They were eventually adopted by Esther. Faith continued to appear carefree, never holding back her giggles or the brightness from her steps. Jada rarely responded in kind.

Not long ago, a group of children accidentally sprayed Jada on the face with their squirt guns, Esther said. Jada erupted in screams and tears.

“The play is no longer there,” Esther said.

Follow Garrett Therolf (@gtherolf) on Twitter

Produced by Lily Mihalik and Evan Wagstaff.

More from the series: A private system |A turnaround in Tennessee

More foster care coverage

Problems proliferate at private foster care agency

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.