One troubled priest who got a second chance

He was given a second chance here, in the High Plains of Texas, where a patchwork of cotton and wheat fields unfurls beneath a giant blue sky.

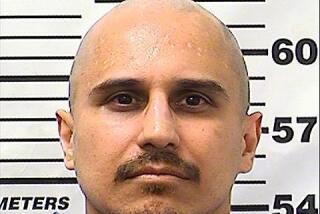

He was no longer Father John Salazar, a name typed across yellowed newspapers and courthouse microfilm more than a thousand miles away in Los Angeles. He was Father John Salazar-Jimenez, the face of Catholicism in this town of emptied grain elevators and darkened shop windows.

Yolanda Villegas adored Father John. A pillar of the Church of the Holy Spirit, she knew nothing of his past. Few parishioners did. Nearly every Sunday for a decade, she arrived for the Spanish-language Mass, knelt in the same pew and wondered how he’d inspire her that week.

“When he lifted the chalice and lifted the host, it almost felt like Jesus was doing it,” Villegas said.

They grew close as Villegas grieved for her daughter who had been killed in a car accident not long before the priest’s arrival in 1991. He later helped her teenage grandson Beau practice Spanish.

One day, in the spring of 2002, he asked Villegas to gather her family. He had something to confess.

::

More than two decades before, Salazar was taking steps to become a priest in his hometown, Los Angeles. He was drawn to the Piarist order because of its work teaching poor children. “They need good men to help form them,” he wrote in neat cursive in October 1979.

At 6 feet tall and about 200 pounds, he towered over the altar boys. He had toffee-colored skin, a welcoming smile. In glowing evaluations, part of thousands of pages of confidential records the L.A. archdiocese and various religious orders released this year, everyone praised the same traits that would later charm Yolanda Villegas.

A parish priest noted, “He has a sense of humor which easily wins even older more conservative members.” At a hospital, “He always asked the patient to pray for him also.”

He chatted up gang members. He comforted the sick and handicapped. “John has a certain charisma that attracts others to him,” one assessment said. “Has almost a power over people.”

His demons, he kept to himself. He had never met his immigrant father. From ages 10 to 12, he said during a psychiatric evaluation, his mother molested him. As a priest, he was drawn to boys only a year or two older than that.

In 1987, Salazar pleaded guilty to abusing two teenage boys and was sent to prison.

“I wanted to run from them, ignore them, talk to them about what was taking place, but I did not have the courage to do so,” he told a sentencing consultant. “I just could not stop and did not know why.”

::

Just before Christmas 1990, Bishop Leroy Matthiesen traveled from his home state of Texas to a mountainous patch of New Mexico. Pine-dotted and serene, Jemez Springs was home to a church-run treatment center for accused abusers.

Salazar had been there since his prison stint in California. He had been banned from the L.A. archdiocese, but like many abusers of his era, he had not been defrocked.

“What I want to believe,” he told his fellow clergymen in a letter during his criminal case, “is that you will treat me as the prodigal son returning back to the Father with open arms and rejoicing.”

In the Catholic Church, it wasn’t an outrageous proposition. Each diocese was essentially run as its own fiefdom, at least in personnel matters. All Salazar needed was a so-called benevolent bishop, someone willing to forgive what the legal system wouldn’t.

The treatment center staff called Matthiesen. He ran the Diocese of Amarillo, where 38,000 Catholics were scattered across the Baptist-heavy Texas Panhandle.

A plain-spoken man raised on a cotton farm, he thought of himself as a friend to his priests, even sharing beer and Doritos with seminarians. By the time he died in 2010, he was widely known for his work protesting nuclear weapons and the death penalty.

Early in his tenure, Matthiesen wrote in his book, a furious parishioner threatened to hang a cleric he said had molested several boys. The bishop confronted the priest. He confessed. “I thereupon ordered him to leave the Diocese of Amarillo before sundown,” Matthiesen wrote.

The bishop later regretted it. Even convicted abusers had a place in the priesthood, he said, though the most dangerous should be kept away from children. “We cannot in good conscience now wash them off our hands,” he wrote.

In Jemez Springs, he sat down with Salazar. “He told me that he had developed a relationship with one of the boys. At that point I didn’t even ask how far that went,” Matthiesen said in an interview for a documentary called “The Scarlet Bond.” The bishop invited Salazar to Texas. “I was never sorry that I did.”

The bishop said he hired at least six more priests from church treatment centers during his tenure. Msgr. Harold Waldow, a retired diocese official, said the actual number is closer to 20. “I sometimes refer to these guys as wounded healers,” Matthiesen said in the documentary. “They could understand the weaknesses of other people.”

In July 1991, Salazar started at Yolanda Villegas’ church. He was still on parole. He soon used the last name Salazar-Jimenez.

At the time, it was common for bishops to shuffle abusers around, but very few had been convicted. Fearing that the Piarist order could be held liable if Salazar molested again, its attorney sent the Amarillo diocese a copy of his criminal file.

In Los Angeles, Cardinal Roger Mahony dashed off a letter to a Vatican representative in Washington, D.C., shortly after he learned Salazar’s career had been resurrected. Matthiesen, he said, was hiring priests who were “seriously disordered” and putting parishioners and the church “at grave risk.”

When Mahony told the Amarillo bishop about his letter, Matthiesen fired back: “I am able to keep careful tabs on all our priests. ... What I observe now is a lot of good taking place.”

::

Halfway between Amarillo and Lubbock, Tulia must have seemed an ideal place to hide. In 2002, the clergy abuse scandal was rippling through the country, but in this town of 5,000 it was easy to ignore. The Tulia Herald carried cotton industry news, bowling team scores, reminders to sign up for Cowboy Church camp.

But back in Los Angeles, the clergy scandal infuriated Carlos Perez-Carrillo, a former altar boy who says he was molested by Salazar when the priest was still in the seminary. Desperate to find out where Salazar ended up, Perez-Carrillo said he called the priest’s old religious order. They wouldn’t tell him.

At a news conference with other members of a victims group, he mentioned Salazar by name. When a reporter found the priest in Texas, the Amarillo diocese barred Salazar from acting as a priest in public, church documents show.

When the priest asked Villegas to gather her family, about half a dozen people crowded into her living room, including her daughter-in-law Jamie, a Baptist who had been considering converting to Catholicism. With Salazar’s help, Jamie’s son Beau had made his confirmation.

The priest who arrived was a shell of his usual self. This was not the man who had overseen construction of a nine-classroom religious education center and been honored for his work on at least three plaques on the small patch of church land. Now he hunched over and sobbed.

He could have told the Villegas family about the conviction in Los Angeles. He could have told them about his time in Jemez Springs. Instead, they say, he told a lie.

Years ago, he said, I had an inappropriate relationship with a young woman. If you hear anything else, it’s not true. It’s not me.

The Villegas family responded by forming a prayer circle. Dear Lord, Jamie prayed aloud, please help Father John.

The church shipped him to a treatment center in Canada. Before he left, he gave the family a card. “I consider myself so blessed even at this most difficult time in my life,” he wrote. “I am so grateful that I could call upon you as my own family.”

By the time he returned, police in Los Angeles were building a case against him. Just before Thanksgiving, Salazar was arrested on suspicion of abusing Perez-Carrillo and another boy in the 1980s. It was his second set of criminal charges.

Yolanda Villegas’ faith in him never wavered. She and her husband, who ran a salon, gave Salazar at least $800 to help pay for his defense. In the summer of 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the California law used to prosecute decades-old abuse cases, and the charges against Salazar were dismissed.

The Villegas family felt vindicated. Salazar came back to Texas without a parish, but they still considered him their priest.

That September, he joined the Villegas clan at a huge family wedding near Dallas. They got him a room at the Days Inn where they were staying. At the reception, 18-year-old Beau downed three rum and Cokes, some Scotch and at least 10 beers. He stumbled around. He threw up.

When he returned to his hotel, Salazar ushered him into his room. I’ll take care of you, he said. Instead, the priest removed the teenager’s pants and forcibly performed oral sex on him, Beau told police. He was so woozy and terrified, he said, that all he could do was clutch his shirt.

That night, he told his grandmother the outlines of what had happened over the phone.

Are you sure, Beau? she asked. Are you telling me the truth?

Yes, he said.

She believed him.

::

In December 2004, Salazar was defrocked. Six months later, he stood trial for sexually assaulting Beau. In a Dallas courtroom with pale gray walls, he sat stone-faced at the defense table, his suit neatly pressed. It was the third time he’d been criminally charged.

He’d told the Dallas Morning News that what happened in the hotel room had been consensual. The Villegas family targeted him because he was a priest, he said, and they were hungry for the church’s money. “I did nothing wrong,” he contended.

The proceedings traced more than two decades of human wreckage.

Perez-Carrillo flew in from L.A. He was 39 with a devoted wife and four children. His advocacy on behalf of clergy abuse victims had worn him down. His prayer group shunned him.

“Why did you continue to go around John if you thought he was molesting you?” a defense attorney asked.

“I didn’t know how to stop it,” he said.

Beau Villegas was now 20 and suffered from severe depression. Going to church triggered flashbacks, and he had started to question whether God even existed. When he testified about the attack, his cheeks reddened and his voice trembled.

“I asked him why he did it,” he said.

“What did he say?” a prosecutor asked.

“And he said it didn’t matter, and he responded that I should do what I have to do but that I was an adult and that I couldn’t take any action.”

Yolanda Villegas testified too.

A prosecutor asked: “Do you address him as Father John today?”

“No.”

“When did you stop calling John Salazar ‘Father John’?”

“The night that I got the call from Beau.”

By then a retired bishop, Matthiesen also testified. He was 84 and had sent letters to parishioners seeking money for ousted priests. One month, he was able to send Salazar $1,266.66.

“And you call him a friend to this day — correct?” a prosecutor asked.

“Yes,” the bishop said.

The jury found Salazar guilty. He was sentenced to life in prison.

After the trial, Perez-Carrillo and Beau Villegas each settled civil claims against the church. So did at least seven others who said Salazar had abused them.

In 2011, the top criminal appeals court in Texas overturned Salazar’s conviction, saying prosecutors had failed to turn over evidence that Beau Villegas was considering a lawsuit. Salazar took a plea deal and was released from prison last year. He did not respond to a request to comment for this story.

Salazar now faces a criminal charge for the fourth time, stemming from a young man who grew up in Tulia and said Salazar abused him years ago. The former priest, his attorney said, maintains that he is innocent.

::

One winter day, Beau Villegas and two other men who said Salazar abused them met at the Church of the Holy Spirit. A harsh cold had settled over the Panhandle.

As part of the young men’s civil settlement with the Amarillo diocese, the three plaques bearing the former priest’s name had been unfastened and placed on the ground. A prayer was said. Holy water was sprinkled on the church.

One by one, each young man heaved a sledgehammer into a plaque, shattering the tributes to Father John Salazar-Jimenez.

que, shattering the tributes to Father John Salazar-Jimenez.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.